- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1868 John Heaps (alias Muley Moloch), a preacher, self-styled prophet, and trained bootmaker, left England with a group of eight women bound for Australia. Their intention was to set up a mission dedicated to the development of their own perfection and a preparation for the Second Coming of Christ ...

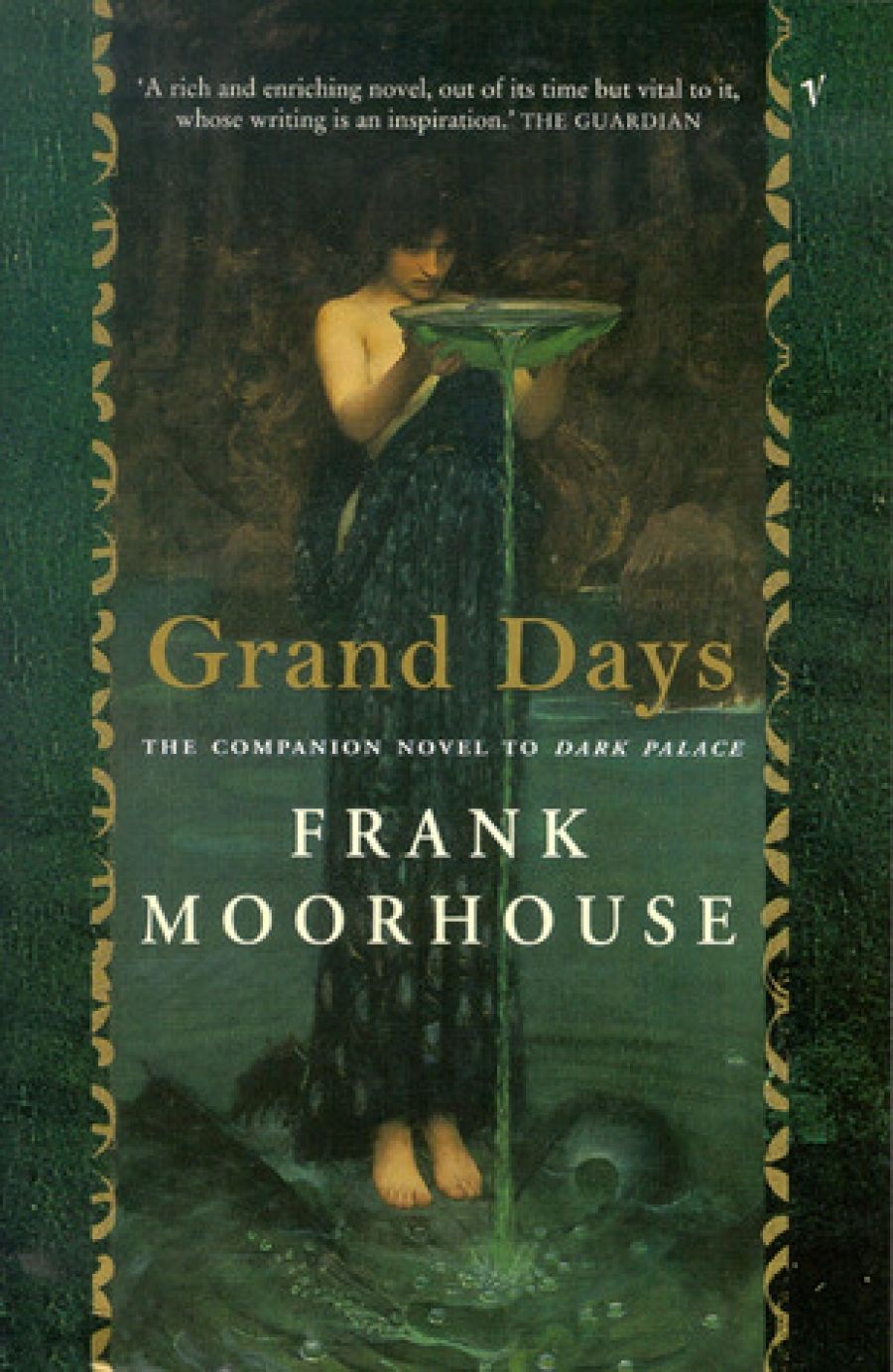

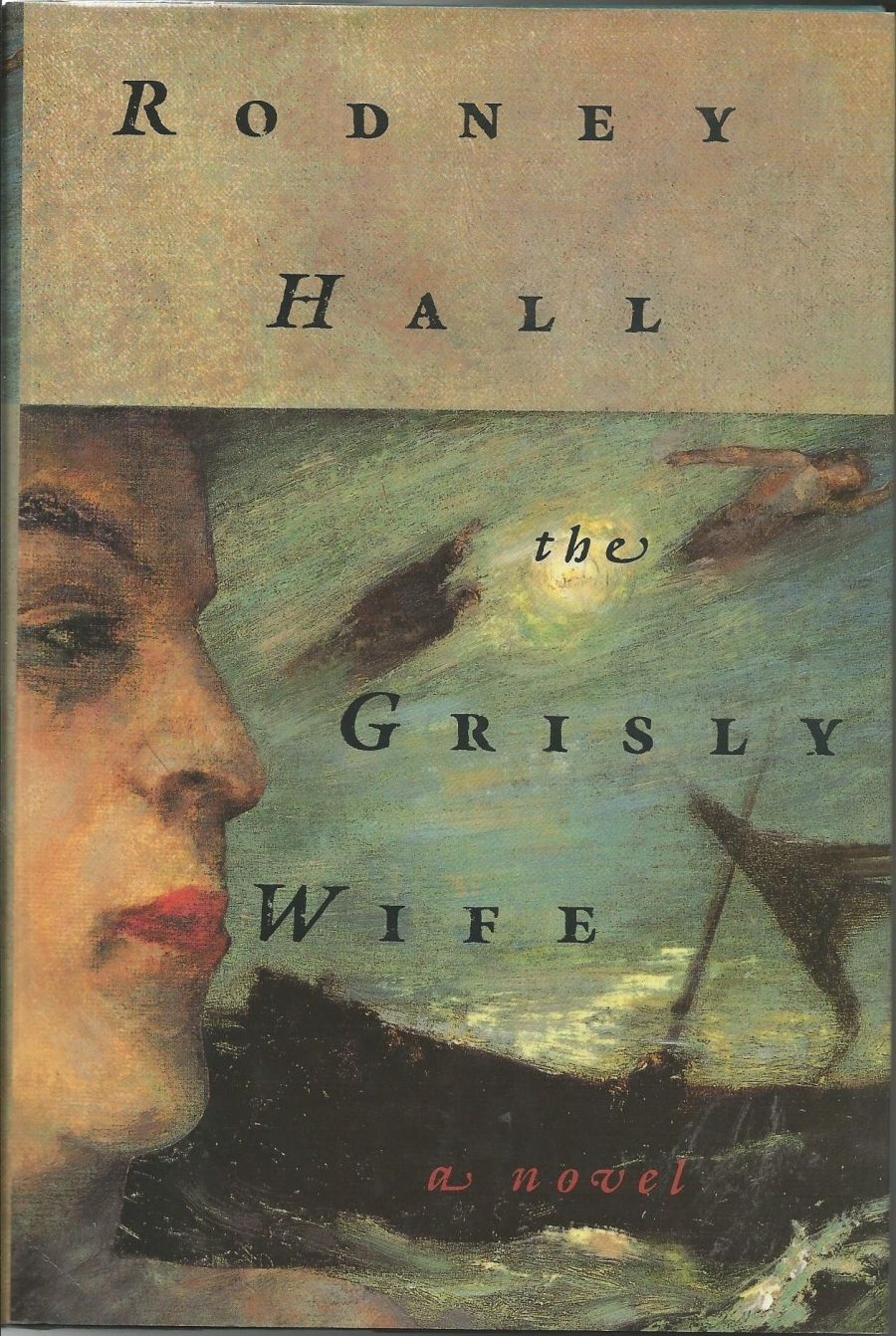

- Book 1 Title: The Grisly Wife

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $35, 0732907764

In 1868 John Heaps (alias Muley Moloch), a preacher, self-styled prophet, and trained bootmaker, left England with a group of eight women bound for Australia. Their intention was to set up a mission dedicated to the development of their own perfection and a preparation for the Second Coming of Christ.

They arrived in Melbourne but found it unsuitable as a New Jerusalem (too superficial and violent), so they moved to the south coast of New South Wales. At Yandilla, a seaside town dominated by Irish Catholics, they set up their protestant mission, but moved inland in 1870 to the preferred isolation of a property in the bush. Here, Catherine Byrne, the prophet’s wife, gave virgin birth to a son Immanuel. Or so it seemed. Along the way her husband had performed a number of miracles which included flying (or at least achieving briefly sustained levitation in a standing position – his shoes rose off the floor) and the bringing back to life of a drowned woman (with whom he then had a sort of immaculate affair to match Catherine’s immaculate conceiving.

One by one the women died of consumption at the mission property while the prophet’s megalomania waxed and his credibility waned. Eventually, the surviving women kicked him out, though not before he had accidentally shot and killed a hairy wild white man (an escaped convict).

The prophet opened a shoe business in town; the immaculate son, having turned out to be probably not immaculate at all, ran away to Ballarat and England; most of the women ended up dead in the mission graveyard; and Catherine Byrne told the whole story to the local policeman in 1898.

That’s it! All rather pointless, really. And that’s the point, I suppose.

Read more: Nigel Krauth reviews 'The Grisly Wife' by Rodney Hall

Write comment (0 Comments)