- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

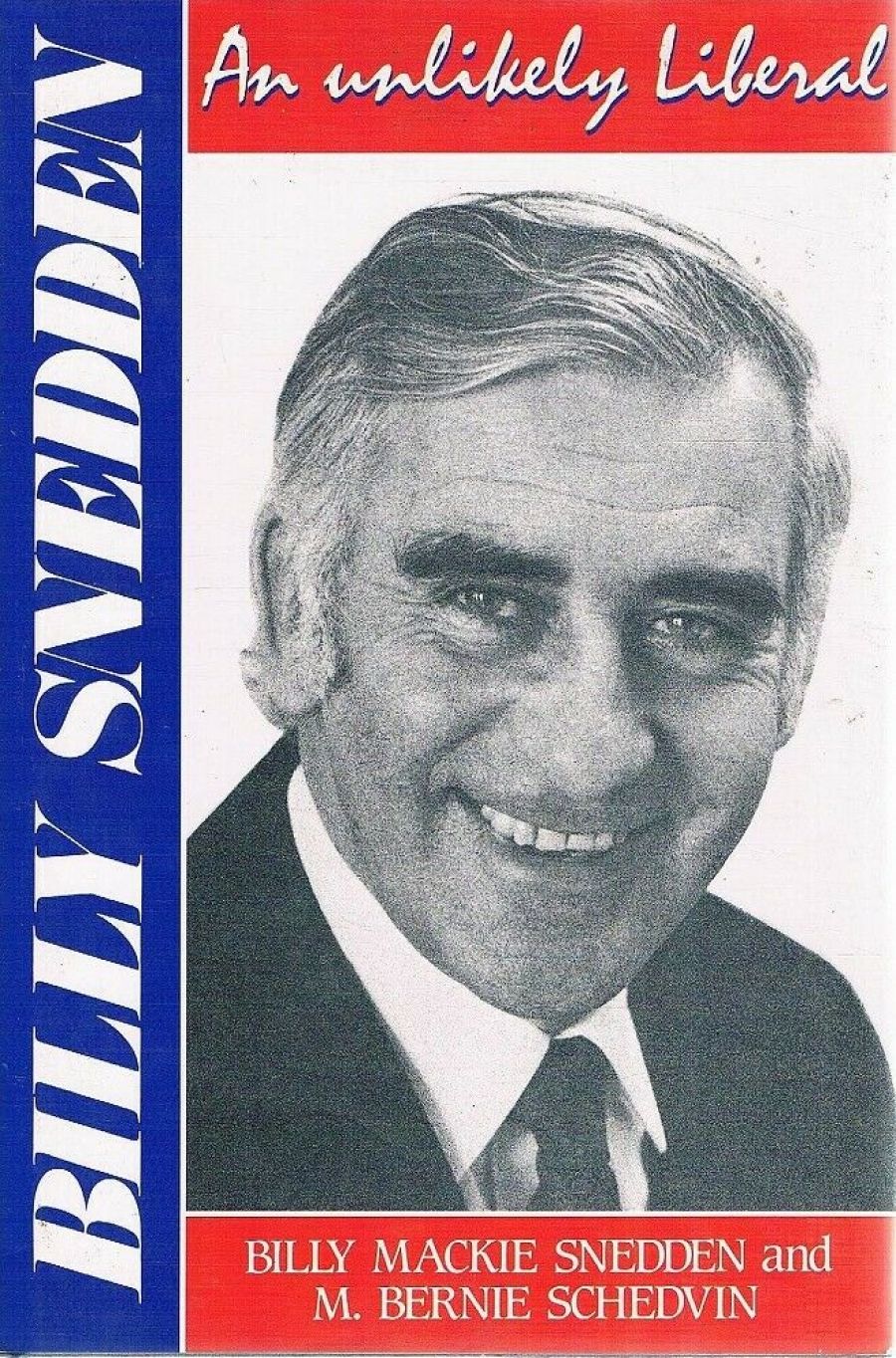

Neither a conventional biography nor an autobiography, Billy Snedden is a story told in two quite distinct and authentic voices. There is that of the late Sir Billy Snedden, Liberal Party leader from 1972 to 1975, and Dr Bernie Schedvin, lecturer in politics at La Trobe University.

It is a tale of a ‘basically good bloke’. Extremely rare for a practising politician, while on the backbench from January 1956, through being Attorney-General and Liberal leader to his election to the Speakership of the House of Representatives, Snedden retained an essential honesty and decency.

Revealingly he said:

Some people have better memories than me and some invent their memories. I am trying to tell you things that I remember as distinct from what people have told me they remember. You are busy, flat out, and you don’t take things too much to heart. I didn’t write them down in a diary. Some people do, and recreate them – all reconstructed afterwards. I have never had any confidence in diaries. Some people go to bed and instead of saying their prayers they make themselves a hero in a diary. I say, ‘Oh Jesus’, save me from that person going to bed at night!’

From the day he entered primary school, Billy Snedden experienced problems with his name. He was not, in fact, christened William. His full name was Billy Mackie Snedden and ‘Billy’ was the name used by his family. As he grew up, most of his friends knew him as Bill and that was how he styled himself during early political campaigning. In the early chapters of Schedvin’s narrative, she has referred to B.M.S. familiarly as either ‘Billy’ or ‘Bill’ according to the usage which prevailed at this stage of his life. In the two final chapters, both ‘Billy’ and Sir ‘Billy’ have been used, varying according to the degree of formality or intimacy implied by the context.

In fact, Snedden was known to his friends both as Billy and Bill. As Dr Schedvin explained, Bill Snedden was not one to stand on formality; he used to say that people would use the form of appellation with which they felt most comfortable – which is what she has done in this quite remarkable book.

As a Liberal member Billy was frequently the target of cartoonists for his embarrassingly honest political comments. The caption of Pickering in the Sydney Morning Herald (11 Dec. 1975) is extremely apposite: ‘I caught Billy telling truths again today … I don’t know where he gets it from.’

Like so many male Australian politicians, sport (cricket, tennis, boxing, and especially Australian rules football) played a pivotal role in Billy Snedden’s life. It is one of the triumphs of Schedvin’s book that the centrality of sport and its intimate connection with politics is made crystal clear.

Immediately after coming to Melbourne in the mid-fifties, Sir Billy trained with South Melbourne VFL side and played, like Mike Willesee, with the Seconds. He subsequently became an active supporter of the Melbourne Football Club which had the same colours as West Perth Football Club where he played in his youth. For two years Billy was a patron of the Demon’s ‘Coterie’. In 1981, shortly after the club was incorporated, he undertook the role of Chairman of its Board for five years. He also became director of the Victorian Football League when the new commission was formed.

When Sir Billy was singled out in an attempted coup of the Melbourne Football Club it was because it was felt his image and the way he spoke set him too far apart from the ‘boots and all’ footballers and ‘ordinary’ club members. He was even labelled by some as a ‘snob’. As Schedvin perceptively explains, this was a ‘complete misperception of the man, totally ignoring his background as a lad from the wrong side of the tracks who had played football in his bare feet for want of boots and later played for Western Australia as an amateur’.

In ‘The Final Years’, Schedvin tastefully deals with Snedden’s separation from his wife Joy:

The distance which had grown between them during the years since he lost the leadership of the Liberal Party became a formal separation after he left Parliament in 1983. Billy moved into a small flat at 201 Spring Street, Melbourne, only a short walk from his offices at 128 Exhibition Street and within easy reach of some of his favourite restaurants.

On Thursday 25 June 1987, following visits to Perth and Queensland, Snedden flew to Sydney for the Liberal Party’s campaign lunch and booked into the Rushcutter’s Bay Travelodge where he usually stayed. After the rally Sir Billy went on for drinks and a meal with companions, a lady whom he had known for some years and a young affianced couple. The conversation largely revolved around business and plans for the future, reflecting Sir Billy’s own hopeful frame of mind at the time’.

After dinner, the party split up and en route back to the Travelodge Sir Billy called in to the crowded bar of the Bayswater Hotel where he placed $50 on the bar and stood drinks all round.

He quickly got into conversation with a group of younger people, including some who were Liberal party supporters. His companion recollected that:

Over the next couple of hours Billy roamed the room and brought back all sorts of people to meet me. It was as if he was on the campaign trail again – brilliant smile, laughing eyes, shaking hands – and mostly aimed at a younger public. He seemed to seek out and be happy with the thirties to forty age group. I don’t think it was chasing after youth so much as trying to hold on to the image of his children.

At about l am Billy returned to the motel with his female companion who left shortly afterwards, thinking him asleep. During the early hours of Friday morning he died of a heart attack, aged sixty.

The story is completed by Schedvin:

‘Some time later friends who had known him from youth were able to smile wryly and say “Typical Bill!”.’ In some ways, the circumstances of Billy’s death were not out of keeping with his lifestyle or character. For Billy, politics had long provided a resolution for anxiety aroused by sexuality and death, which from his youth had troubled him so deeply. In his final hours these fundamental themes combined. There is a poignancy in the fact that this positive and forward-looking man died with hopes and dreams of the future rekindled. In retrospect, his companion reflected that during those final hours Sir Billy had reminded her of ‘a candle that flares brightly before it gutters out, but that is a poor analogy. Rather perhaps the sun as it sinks into the horizon appears to grow larger and larger, the colours more and more brilliant, and just before it reaches its most dazzling – it is gone – and all that is left is a slight chill in the air.’

An absolutely dreadful preface by Andrew Peacock does an absolute disservice to the book’s integrity and intent.

That aside, An Unlikely Liberal, especially because of Bernie Schedvin’s contributions, is thoroughly recommended.

Comments powered by CComment