- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

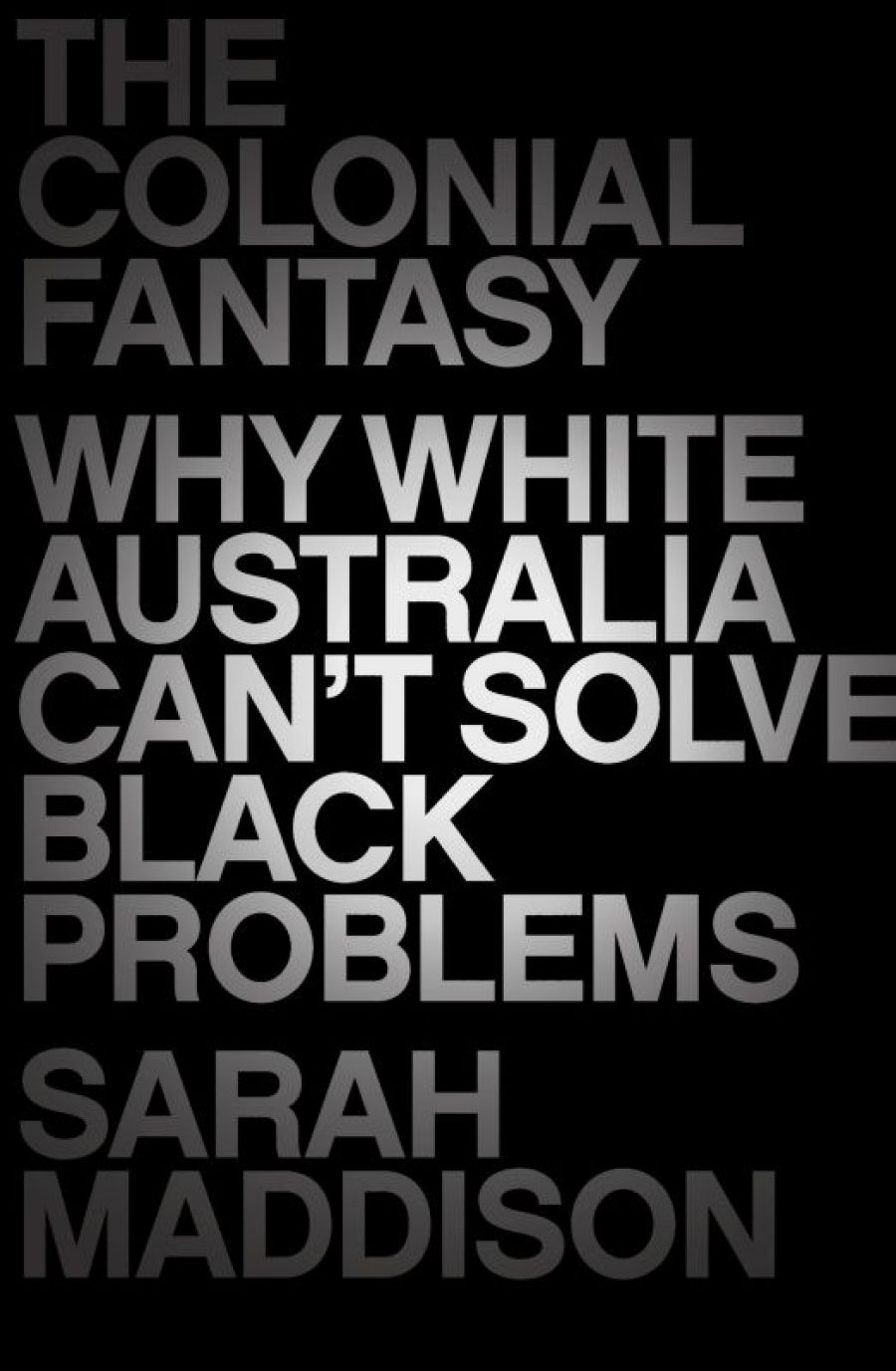

- Custom Article Title: Richard J. Martin reviews <em>The Colonial Fantasy: Why white Australia can’t solve black problems</em> by Sarah Maddison

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Fuck Australia, I hope it fucking burns to the ground.’ Sarah Maddison opens this book by quoting Tarneen Onus-Williams, the young Indigenous activist who sparked a brief controversy when her inflammatory comments about ...

- Book 1 Title: The Colonial Fantasy

- Book 1 Subtitle: Why white Australia can’t solve black problems

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 336 pp, 9781760295820

Central to this book is Maddison’s critique of policies such as Reconciliation, the Apology to the Stolen Generations, Closing the Gap, and the campaign for Constitutional Recognition. Drawing on the influential formulation of Australian historian Patrick Wolfe, she argues that each of these approaches conforms to the underlying logic of settler colonisation with its desire to ‘eliminate’, by which she seems to mean not just physical extermination but the ‘assimilation’ of Indigenous people through the structural encapsulation of Indigenous political difference by ‘the settler state’. To dispel ‘the colonial fantasy’, Maddison calls for a reorientation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people’s efforts away from constructive engagement in policy development towards support for Indigenous ‘refusal’ and what she describes as a ‘resurgence that is already underway in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations around the continent’.

‘Refusal’ and ‘resurgence’ are political theories developed by North American Indigenous scholars like Taiaiake Alfred, Jeff Corntassel, Audra Simpson, and Glen Coulthard. Refusal, Maddison explains, ‘encourages an ongoing, watchful, and critical mode of conduct’ among Indigenous people that urges them to ‘turn away from the settler state’. Resurgence is closely linked to refusal, and ‘means actively restoring and regenerating Indigenous nationhood, focusing on transforming alternatives to settler colonial dispossession’ that involve ‘a turn towards Indigenous institutions, values, and ethics’.

For Maddison, refusal and resurgence in the Australian setting involve a ‘regeneration of place and nation-based Indigenous identities that are expressed and governed through culturally appropriate political formations’. Of course, readers will note that efforts to foster ‘culturally appropriate’ Indigenous political formations have long formed part of Indigenous policy, at least since the 1970s. Since that time, Indigenous political formations have flourished in the form of land councils and Indigenous corporations, as well as various kinds of representative organisations like the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1990–2005) and the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples (2010–). More recently, Indigenous businesses have also flourished.

However, Maddison is strikingly ambivalent about existing Indigenous political formations. She tends to appraise historical experiments in self-determination as failing due to what she sees as systemic limits to Indigenous empowerment set by ‘the colonial state’, while nevertheless calling for further and stronger self-determination. Indeed, Maddison depicts Indigenous organisations ‘intended to function as organs of self-determination’ as instead working to effect ‘the dilution of challenges to settler colonial domination’, arguing that ‘corporate self-determination’ obscures true ‘Indigenous jurisdiction’. Her assessment of the Indigenous business sector is similarly ambivalent, praising some enterprises that market traditional knowledge, while worrying that stories of Indigenous business success risk diverting attention away from the need to critique ‘settler colonial developmentalism’ and to de-colonise.

True Indigenous jurisdiction exists for Maddison in Indigenous political formations ‘linked to cultural practices that are deeply traditional’. This requires the ‘disentangling of Indigenous and settler modes of governance’ to reinstitute tradition, particularly in places ‘where colonialism has damaged systems of authority and decision-making in communities’. However, it is unclear exactly which contemporary Indigenous practices are to be considered ‘deeply traditional’, as Maddison does not discuss cultural difference beyond assertions such as ‘land equals life’. There is also no discussion of adaptation and change, or the complex kinds of relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous identity that scholars have addressed through the concept of the ‘intercultural’.

This is the most interesting and troubling aspect of this book. In parts of Australia, Indigenous polities with their source in traditional laws and customs do survive, albeit in adapted forms, and it is interesting to think about how they should be recognised and resourced by the state. In the Gulf Country, where I have worked for many years, a number of different types of polities have developed from different experiences of colonisation affecting Indigenous people on either side of the Northern Territory–Queensland border. ‘Disentangling’ authentic Indigenous polities from those deemed to be contaminated by the wider society in settings like this will be difficult and will involve invidious decisions that will privilege some Indigenous people and disadvantage others. Whether the old polities, which Maddison calls ‘clans’ (i.e. estate groups) and ‘nations’ (i.e. language groups or regional groups), are better equipped to achieve success than existing Indigenous political formations is of course another question.

In other parts of Australia, Maddison seems to acknowledge that it is already too late for refusal and resurgence to be effective strategies of de-colonisation, as she describes the loss of knowledge of ‘distinctive ways of living and relating’ as inhibiting ‘the capacity to (re)imagine Indigenous independence’ in the Northern Territory (and by extension it seems most of the rest of Australia). In such settings, Maddison’s recommendation of tradition as the basis for funding decisions made by the state would seem to force Indigenous people to perform authenticity in return for funding and related resources, which can become a repressive expectation (as numerous researchers including Patrick Wolfe have warned). While perhaps aligned with political strategies aimed at achieving local control of resources, such traditionalism risks distracting attention away from the realpolitik of effective Indigenous political formations, organisations, and businesses in places like Sydney and Melbourne.

But it seems churlish to take such arguments as literally comprising actual policy advice relating to Indigenous people. Instead, what is being presented here is the idea of Indigenous tradition, which is really being positioned as a counterfactual in order to critique aspects of Indigenous policy. At its best, this effort suggests new ways for Indigenous people to think themselves free from the epistemological boundaries of colonialism, to pursue an Indigenous ‘sovereignty of the mind’ (as Waanyi author Alexis Wright puts it), which may well result in new kinds of Indigenous political formations such as a Voice to Parliament. The risk is that this effort to critique Indigenous policy by de-historicising Australian colonisation simplifies the kinds of problems and choices that Indigenous people face today, endorsing solutions that sidestep the most difficult questions of continuity and change.

Comments powered by CComment