- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

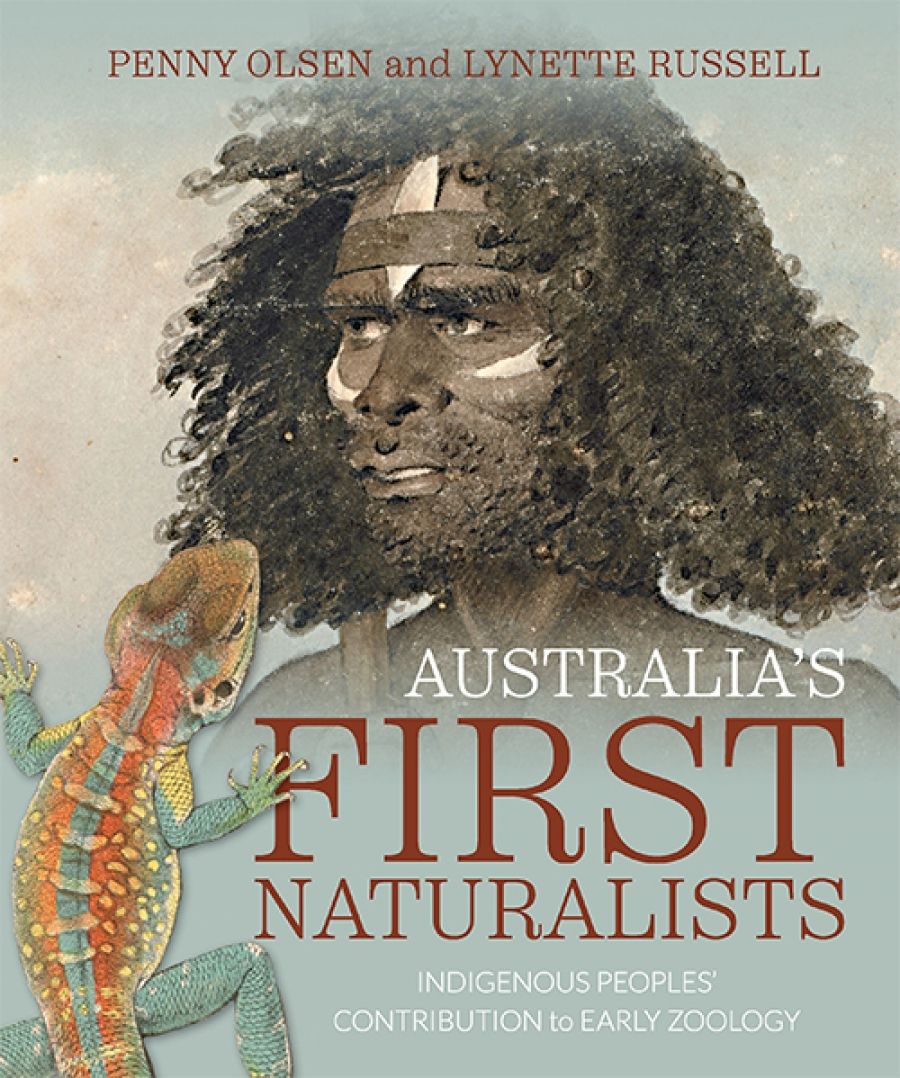

- Custom Article Title: Anna Clark reviews <em>Australia’s First Naturalists: Indigenous peoples’ contribution to early zoology</em> by Penny Olsen and Lynette Russell

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What does it mean to really know an ecosystem? To name all the plants and animals in a place and understand their interactions? To feel an embodied connection to Country? To see and hear in ways that confirm and extend that knowledge?

- Book 1 Title: Australia’s First Naturalists

- Book 1 Subtitle: Indigenous peoples’ contribution to early zoology

- Book 1 Biblio: NLA Publishing, $44.99 pb, 223 pp, 9780642279378

The gravesite of Yuranigh near Molong, New South Wales (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

The gravesite of Yuranigh near Molong, New South Wales (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

A generation ago, the archaeologist John Mulvaney offered the then radical argument that Europeans didn’t enter a timeless and changeless land when they colonised Australia (The Prehistory of Australia, 1978). Yet these interlopers also must have recognised that the land wasn’t terra nullius, but had been sung, walked, mapped, and painted for millennia. That they understood this is confirmed by the ways in which they were dependent on Indigenous assistants to translate the natural world. Australia’s First Naturalists explores those deep knowledges and how they were applied, co-opted, and capitalised upon by European scientists and explorers in their quest to comprehend the continent they were seeing.

The nineteenth century witnessed an explosion of Western science, which is rightly celebrated for expanding understandings of the natural world. But that knowledge was also covetous and acquisitive. In an age of discovery and exploration, the natural sciences also became sites of colonial advancement and authority.

’In the words of the marine biologist Gilbert Percy Whitley, Aboriginal people had ‘intimate knowledge of every living thing, but they had no written records’. By contrast, the colonial urge to know and name inserted everything into textual schema (though they needed Indigenous assistants to broker that knowledge). With beautiful illustrations from the National Library of Australia, and accessible (yet never simplistic) writing and explanation, this book is a vivid introduction to some of the questions and troubling paradoxes in that complex relationship over place and nature in the colonial scientific contact zone.

After all, this moment of disciplinary expansion coincided with ‘scientific’ theories of evolution and race. Hierarchies of human ‘civilisation’ were quick to plot indigenous peoples, and Australian Aboriginal people in particular, at nascent stages of human development. In some nineteenth-century immigrants’ guides to Australia, for example, Aboriginal people were included within sections on flora and fauna – despite being central to the accumulation of that knowledge in the first place.

Specimen jars increasingly filled newly built museums, and studies of the natural world were professionalised into fields of ichthyology, zoology, ornithology, and botany, overlaying new systems of knowledge across a country that was quickly depleted of its Indigenous epistemologies. ‘By the twentieth century,’ Olsen and Russell explain, ‘with the assistance of Indigenous people, nearly all Australia’s vertebrates had been discovered and described by scientists, while many Aboriginal people had been forced from or left their country.’

The numbers and cataloguing details of such scientific collections are staggering. Hundreds of thousands of birds, fish, marsupials, and monotremes were captured, recorded, and meticulously classified. By contrast, the names these scientific pioneers often gave to their Indigenous assistants were notoriously generic and vague: references to ‘Jacky’, ‘Blacky’, and ‘Old Jim’ recur in scientific and exploration records; ‘maker unknown’ is prevalent in the providence of museum displays of Aboriginal artefacts. Both reveal the unevenness of the archive in its acknowledgement of Indigenous contributions to Australian science.

A group of Indigenous Australians at Port Essington, including Neinmal (third from left), who spent two years assisting John MacGillivray on land and aboard HMS Fly (photograph via The Wild Reed)

A group of Indigenous Australians at Port Essington, including Neinmal (third from left), who spent two years assisting John MacGillivray on land and aboard HMS Fly (photograph via The Wild Reed)

But there are also lovely stories of companionship and genuine interest, which the book catalogues with historical context and empathy, such as Scottish naturalist John MacGillivray’s collaboration with Neinmal (an Iwaidja man) in the Port Essington region in the mid-nineteenth century. Despite the complicity of scientific disciplines in the colonial project, it’s difficult not to be moved by the colossal natural bounty these naturalists recorded – before waves of pastoralism, population growth, and industrialisation impacted Australia’s ecosystems.

In a recent essay (Griffith Review 63), Tom Griffiths describes the Anthropocene as a ‘profound rupture’ in the history of the natural world, where mass extinctions, fish deaths, and disappearing rivers are regularly reported. This moment of rapid and systemic ecological change sees ecologists turning to Indigenous knowledges to develop management strategies for Australian ecosystems. Environmental historians recognise Indigenous archives in the land itself that reveal how it was managed, observed, and understood in the past. Indigenous Ranger programs have been adopted on northern cattle stations, conservation zones, and national parks in an attempt to recuperate country.

As well as being a history, there is also a message to the future in this book: the bounty that colonial naturalists were so struck by is also alarmingly fragile. And the increasing (but belated) turn to Indigenous knowledges could be key in responding to that profound rupture.

Comments powered by CComment