- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Michael Winkler reviews <em>A Stolen Life: The Bruce Trevorrow case</em> by Antonio Buti and <em>My Longest Round</em> by Wally Carr and Gaele Sobott

- Custom Highlight Text:

Philip Larkin famously suggested that ‘they fuck you up, your mum and dad’, but the alternative is usually worse. Twenty years before Larkin wrote ‘This Be the Verse’, his compatriot John Bowlby published Maternal Care and Mental Health (1951), which described profound mental health consequences when ...

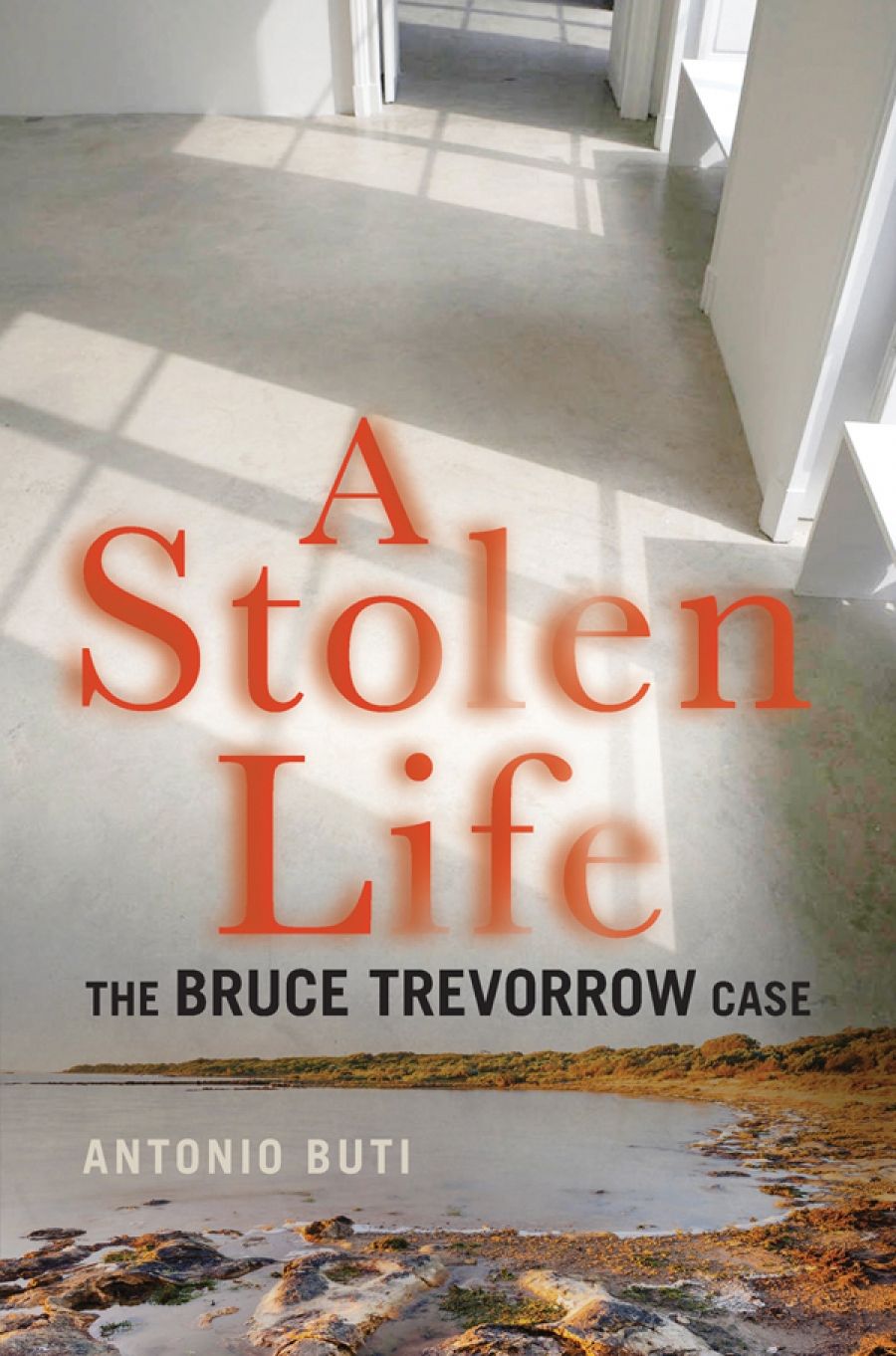

- Book 1 Title: A Stolen Life: The Bruce Trevorrow case

- Book 1 Biblio: Fremantle Press, $32.99 pb, 292 pp, 9781925815115

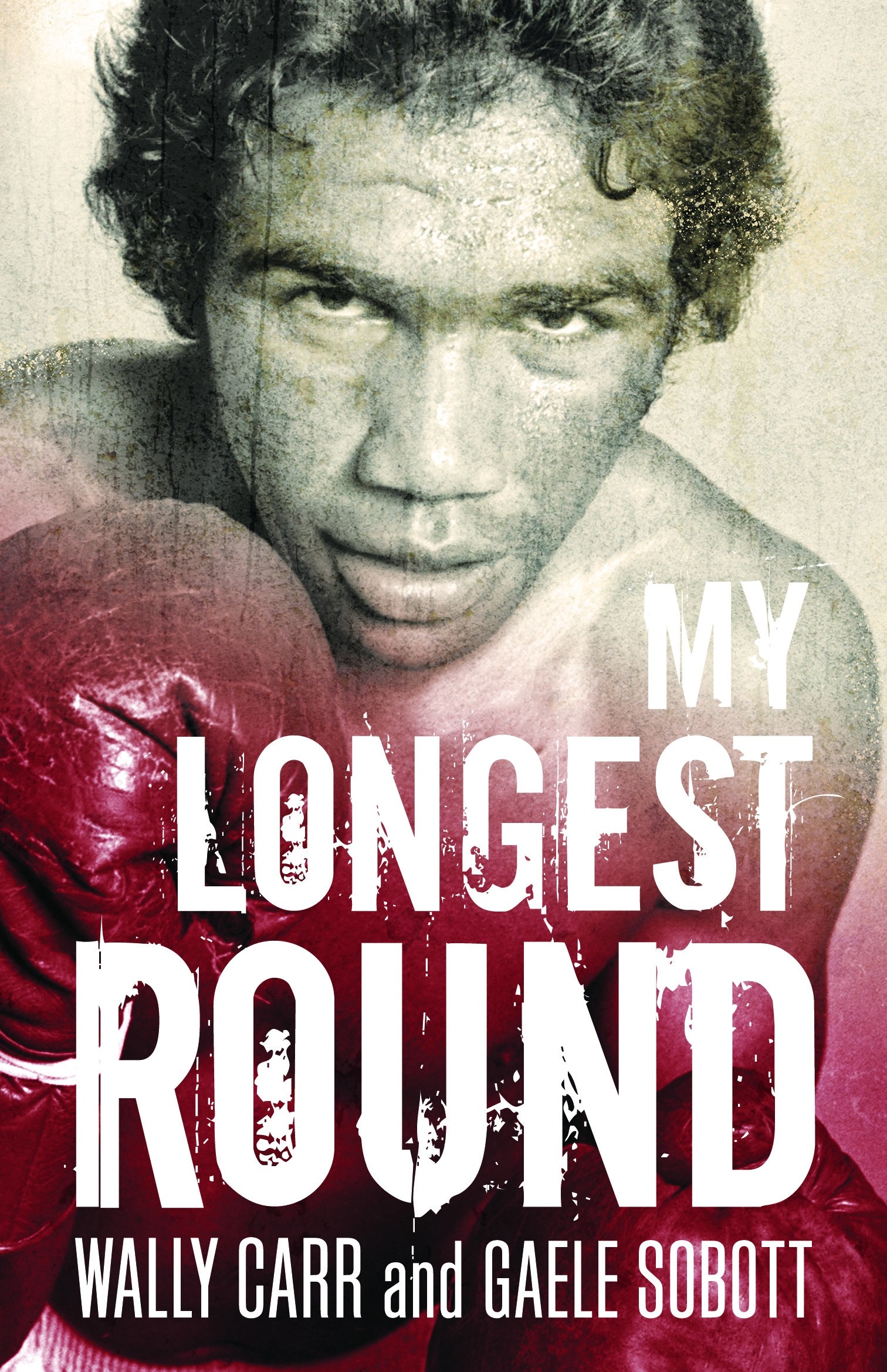

- Book 2 Title: My Longest Round

- Book 2 Biblio: Magabala Books, $19.99 pb, 232 pp, 9781921248504

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2019/August_2019/my_longest_round_high_res_.jpg

Dr Antonio Buti revisits Trevorrow v South Australia in A Stolen Life. As a lawyer and legal academic, Buti is well credentialled to provide insights into what transpired in the Adelaide courtroom, and why and how former Justice Tom Gray found in favour of Trevorrow. Buti draws extensively on court transcripts, interposing clarifying aperçus and giving a strong sense of the legal arguments and tactics. Julian Burnside QC and the sedulous team acting for Trevorrow shine in this telling. Stephen Walsh QC, leading the defence for the State, may be less enamoured with his portrayal.

The hero of the piece is Justice Gray, ‘the decision-maker [who] has to test two truths in conflict’ after opposing counsels have relayed ‘the facts from their standpoint, a contextual truth’. Buti argues that Justice Gray’s finding in favour of Trevorrow ‘shifted the judicial interpretation of historical evidence and acted as a catalyst for a reparations or redress scheme’. However, a ‘national reparations scheme remains elusive’ and the precedent value of his decision remains unclear.

In making his determination in this case, Justice Gray took guidance from Justice Dyson Heydon that the trier of fact is not involved in ‘the finding of historical facts on a balance of probabilities, but the assessment of the value of a chance’. What an evocative phrase that is: the value of a chance. How little chance Trevorrow ever had. Equally powerful is this exchange between lawyer and plaintiff:

Burnside: Could you tell His Honour where you think you belong?

Trevorrow: Nowhere.

Better decisions by author and editor could have improved this useful book. Choosing the past rather than present tense would have made the prose less awkward. The credibility of the courtroom scenes, otherwise carefully built on records and fact-finding, is undermined by Buti’s imagining, in his words, ‘the conduct and thought process of Justice Gray’. He portrays the judge musing to himself on free-range chickens, Christmas, Habakkuk, sport, birth pangs, Remembrance Day. He guesses what His Honour is thinking in response to witnesses and evidence throughout the hearing. It diminishes the author’s research.

Buti notes that trials operate ‘according to procedure shaped by soulless bureaucracy’. It might be argued that there is something bleakly recursive about trying to ameliorate wrongs wrought by bureaucrats in the past by working within the bureaucratic legal system, when both cause and ‘cure’ are products of colonialism.

Symptoms of colonialism’s ongoing impact include dispossession, dysfunction, addiction, family pain. These scourges are abundant in My Longest Round, a headlong rush of first-person reminiscence. At times the text reads like slam poetry in rich Aboriginal English, Carr’s voice unspooling in a rush of memories and digressions. Late in the book, Carr confides that he has brain damage; he is uncertain whether it has been caused by boxing, innumerable street fights, alcoholism, substance abuse, or a combination of these and other factors. He died in April this year, adding poignancy to this testament.

Portrait of boxer Wally Carr at Ern McQuillan Senior's gym at Wilson Street, Newtown, New South Wales, 7 November, 1976 (photograph by Ern McQuillan, via National Library of Australia PIC Online access #PIC/14701/20)

Portrait of boxer Wally Carr at Ern McQuillan Senior's gym at Wilson Street, Newtown, New South Wales, 7 November, 1976 (photograph by Ern McQuillan, via National Library of Australia PIC Online access #PIC/14701/20)

The first third of the book, outlining his rural upbringing, is eloquent social history. The threads of Carr’s story become significantly harder to follow once he moves to Sydney and starts boxing. He fought in every weight class from featherweight to heavyweight and won titles in six divisions, but too many of his hundred bouts are referenced. Focusing on the most important fights would have uncluttered the narrative.

The pungent vernacular, one of the book’s strengths, is rarely explained. A reader who doesn’t know the definition of brasco, roscoe, swy, or ‘bing and swing’ may wish for a little more assistance from Carr’s co-author, Gaele Sobott. Carr also has a habit of listing names as if flicking through a teledex. Figures as diverse as Johnny Lewis, Christopher Flannery, and Kerry Packer are mentioned in passing, without explanation of their role in society, along with scores of others. Newtown halfback Paul Hayward is referred to numerous times, then disappears with no acknowledgment of his early death or his conviction for smuggling drugs from Thailand.

In the latter part of his boxing career and for years afterwards, Carr was a pool shark, pub Lothario, heavy user of drugs (he thinks he lost the most from marijuana use: ‘the yarndi stole my dreams’), and chronic drinker. His health was in tatters, he had depression and was sometimes homeless. Somehow in the last portion of his life he transformed himself, shut down his addictions, and strengthened his bonds with family members. After following him through the tumult of his sporting career and subsequent saturnalia, it is a pity the reader is not rewarded with insights into how Carr rectified his life, and any reflections from those final years.

On the day Carr’s parents were due to marry, his father committed suicide; his mother was seven months pregnant at the time. Carr believes he inherited this damage. ‘I felt like the 22 [sic] bullet that travelled through my father’s brain, just kept on going through my mother’s life and through my life causing injury and pain.’ It is a powerful individual expression of the generational trauma endemic in Indigenous communities.

Buti refers to the legal concept of novus actus interveniens, ‘snapping the causal chain’. In 2008, Kevin Rudd delivered the Apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples. In the following ten years, the number of Indigenous children in out-of-home care doubled. What will be the long-term impact for this generation of children, and what are the wider ramifications for Australia if the causal chain of cultural dislocation and familial fragmentation is not snapped? Larkin’s poem offers a grim clue in its concluding stanza: ‘Man hands on misery to man. It deepens like a coastal shelf.’

Comments powered by CComment