- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

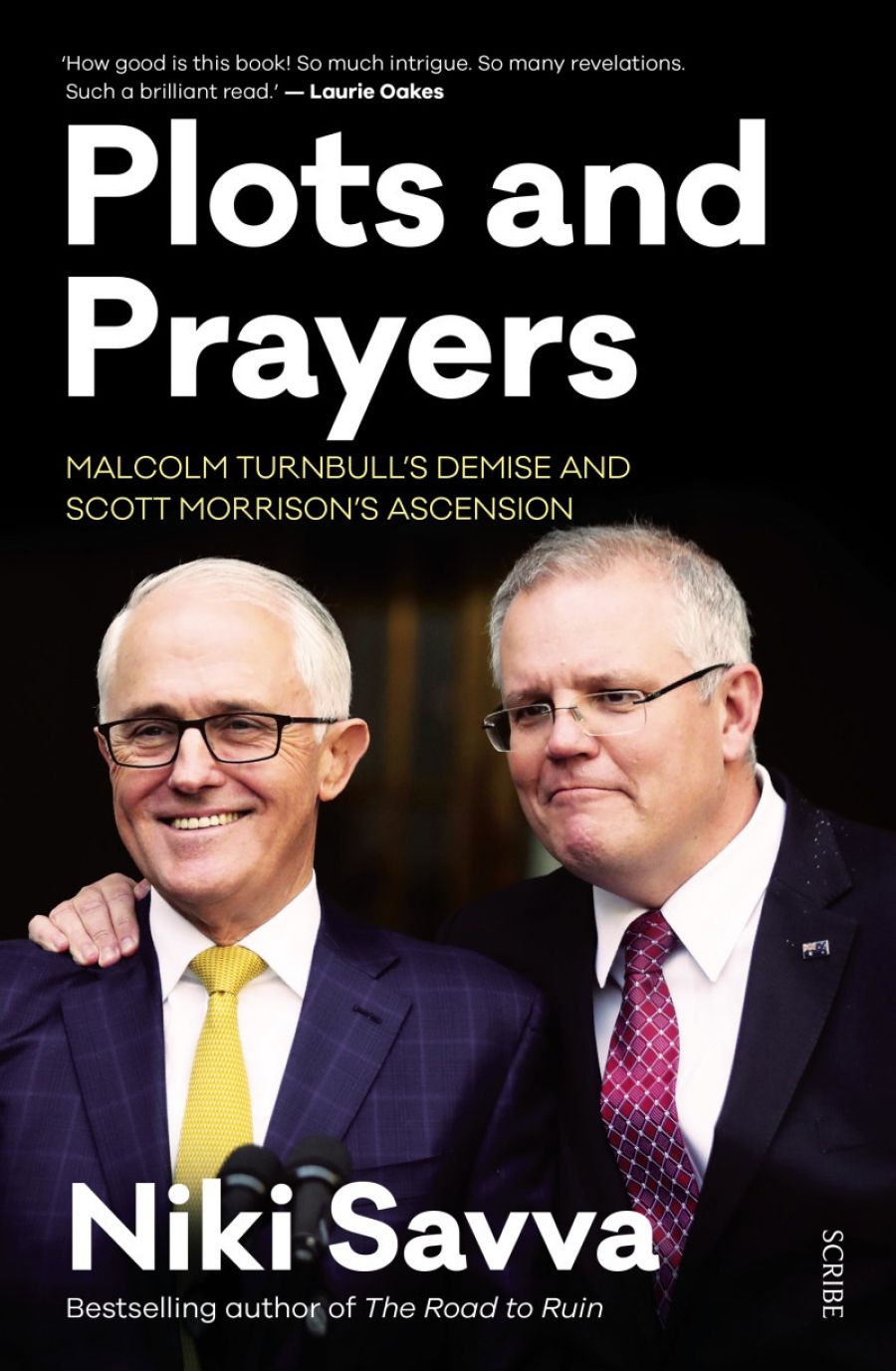

- Custom Article Title: Paul Williams reviews <em>Plots And Prayers: Malcolm Turnbull’s demise and Scott Morrison’s ascension</em> by Niki Savva

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

It’s a challenge to navigate the maze of books published after an election as winners and losers pore over the entrails of victory and defeat. It’s even more challenging when that election delivers a result almost nobody expected. Who’s telling the truth? Who’s lying to protect their legacy?

- Book 1 Title: Plots And Prayers

- Book 1 Subtitle: Malcolm Turnbull’s demise and Scott Morrison’s ascension

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $35 pb, 408 pp, 9781925849189

This book’s strength is Savva’s ability to get most if not all voices on the record. Indeed, there are more than a few Liberals willing to share salacious details that would, frankly, shock anyone who still believes that a politician’s enemies are found only on the other side of the house. Apart from post-coup confessions of anti-Turnbull plotters that would make even Machiavelli blush, there is, for example, the description of Prime Minister Scott Morrison by the now-retired Michael Keenan as an ‘absolute arsehole’. Similarly, Christian Porter ‘did not think Morrison was a team player’, while Finance Minister Mathias Cormann ‘had seen Morrison up close now, and, in his opinion, Dutton was better’.

Savva has some cheeky fun with her subjects. Chapter Three, detailing the marital woes of former Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce, is titled ‘Barnaby’s doodle’. Later, Joyce’s then media adviser Jake Smith, allegedly carpeted by an increasingly irascible boss, wonders ‘how the deputy prime minister gets his staffer pregnant, and somehow it’s the fault of the gay guy?’

Savva doesn’t shy away from the gravity of what transpired last August when another Australian prime minister was cut down in revenge as much as in fear of electoral defeat. We learn how Christopher Pyne, a Turnbull ally, openly wept as he returned home after the coup, and how Dutton’s friend Luke Howarth described that week as ‘pretty shitty’. Savva uses colourful quotes not only to triangulate evidence but to humanise politicians so often perceived as robotic.

It’s critical, then, that Savva, a self-described ‘conservative leftie’, doesn’t overtly take sides, even though readers will probably hear a sympathetic timbre for Turnbull, and will catch a whiff of contempt for Turnbull’s initial challenger, Peter Dutton, for Turnbull’s arch-nemesis, Tony Abbott, and for Mathias Cormann, whose desertion of Turnbull late in the game (after pledging loyalty) sealed his leader’s fate. Even here Savva is fair. She asserts, for example, that Turnbull was a good prime minister but a terrible politician. In what may surprise some people, Savva attests to Dutton’s personal likeability and the fact that he was – at least until the August putsch – better liked in the party room than Morrison, with more friends across the factional divide.

It is, then, the constitution of Morrison the man, and not just any alleged role in the coup, that forms the kernel of this book. For Morrison, the key to success during that week in August, and at any subsequent general election, was to appear to the Australian people as a ‘cleanskin’ – a man loyal to Turnbull and with no blood on his hands; a man reluctantly drafted as a compromise ‘centrist’ candidate between the left-leaning Julie Bishop and the hard right’s Dutton.

It’s the unpicking of this carefully crafted perception that will probably prove this book’s most enduring legacy. Savva offers, for example, strong evidence that Morrison – and, if not Morrison, then Morrison’s ‘numbers men’ Alex Hawke, Stuart Robert, Steve Irons, and Bert van Manen – countenanced his prime ministership long before the Dutton spill. Savva concludes that Morrison did not initiate the coup and confirms that Morrison, who had worked so well as Turnbull’s treasurer, would never challenge his boss while Turnbull held the job. But Morrison was free to move when Turnbull quit after being presented with forty-three rebellious signatures (more than half the party room of eighty-five). It seems that Morrison and his lieutenants were ‘ready for [the spill] and took full advantage of it. They will not admit to plotting, but they will admit to preparing and planning, and then only in that final week, or, in Morrison’s case, the final days.’

Critically, Savva’s account of that planning paints Morrison as a keen political animal. Hungry for power, this allegedly real Morrison is far removed from the popular perception of ScoMo as a ‘daggy dad’. Morrison, Savva argues, gamed Dutton with aplomb, directing around ten of his supporters in the first spill – just enough but not too many – to vote for Dutton (whom Morrison disliked, with the feeling reciprocated) to inflate Dutton’s support so that Turnbull would be sufficiently destabilised (and his prime ministership crippled), while filling Dutton with a false sense of security. In the second spill days later, Julie Bishop in the first round received just eleven votes (no fellow West Australian voted for her), Dutton thirty-eight, and Morrison thirty-six. With Bishop eliminated, Morrison defeated Dutton narrowly, forty-five votes to forty. Had just three MPs changed allegiances, Australian history would have been very different.

The execution of the Dutton spill is therefore revealed as a shambles, and Savva’s account of shifting party loyalties reveals not one or two Liberal parties but as many as four, including three mutually suspicious conservative tendencies: the ‘delcons’ (delusional conservatives) among the hard-right Abbott group; the Dutton-led mainstream conservatives; and Morrison’s evangelicals. While presenting yet more evidence – if anyone still needed it – of Abbott’s white-anting of, first, Turnbull and, second, Morrison himself, Savva cogently argues (contrary to political commentary at the time, including by this reviewer) that Dutton was not Abbott’s ‘trojan horse’. Instead, given the growing distance between Abbott and Dutton (Dutton was never going to reward Abbott with a ministry, Dutton says), Savva describes Abbott as Dutton’s ‘stalking horse’: Abbott would ride back into the Liberal leadership after Dutton inevitably lost the 2019 election.

Savva, after writing her first book So Greek: Confessions of a conservative leftie (2010), said she had only one book in her. Then, after writing the well-received The Road to Ruin (2016), she told friends and family ‘to feel free to slap [her] if [she] ever looked like writing another’. It will be a loss to political journalism if this third volume is Savva’s last.

Comments powered by CComment