- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

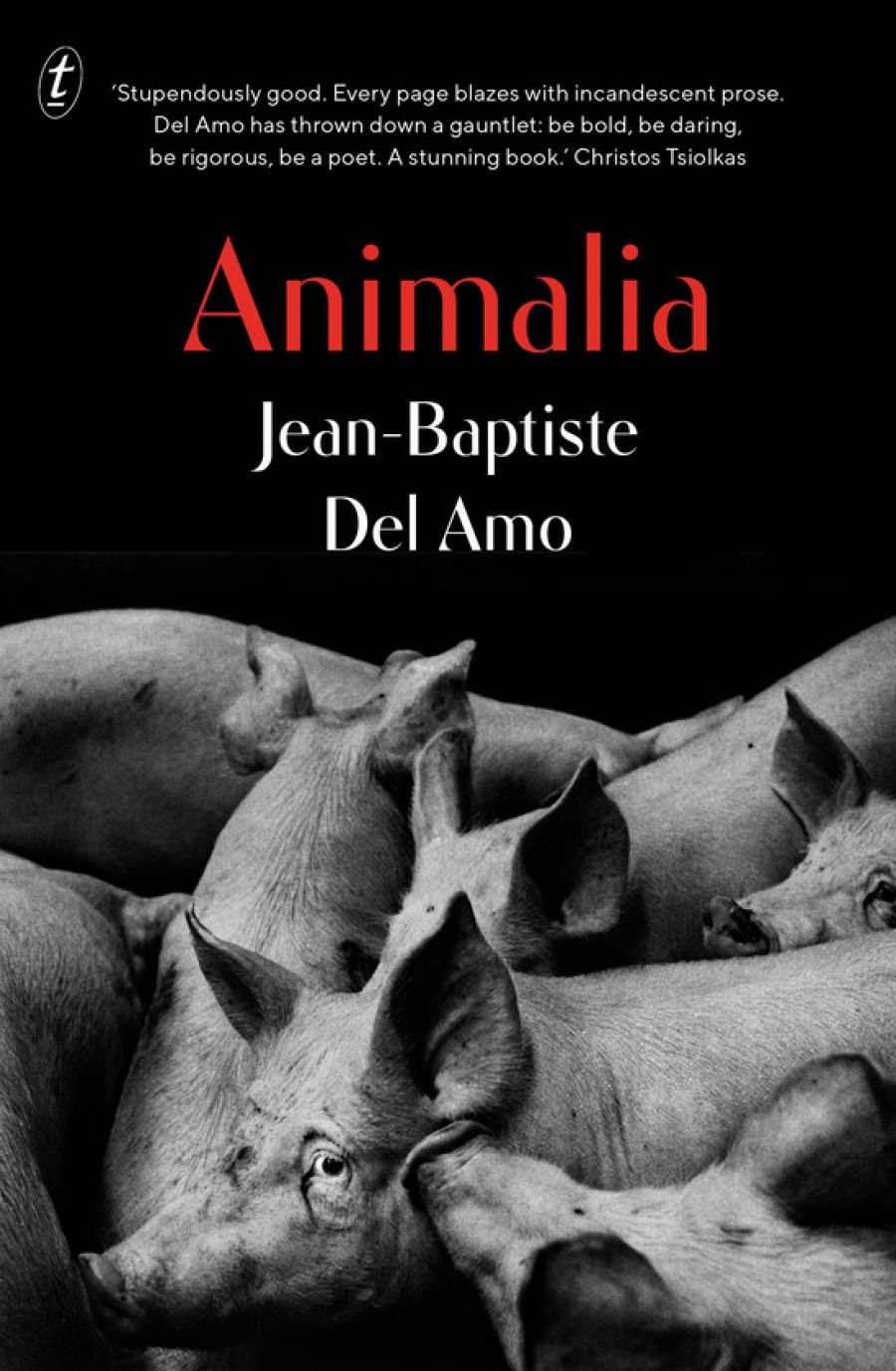

- Custom Article Title: Phoebe Weston-Evans reviews <em>Animalia</em> by Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, translated by Frank Wynne

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If you’re squeamish, this book probably isn’t for you. Each page delivers shocking or mundane violence and descriptions of guts and gore so frank they become a kind of poetry. There is clear relish in Del Amo’s depictions, and there is nothing gratuitous about them; he brings us rivetingly close to each fold of decrepit skin, the agonies of labour ...

- Book 1 Title: Animalia

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 424 pp, 9781925773767

The poetic, sensual treatment of the minutiae of deliquescence and dissolution climaxes with the drawn-out decline of the father: ‘in the faecal magma of the abdomen, a silent army emerges’. Del Amo never passes up an opportunity to describe the body’s afflictions, from mild pruritus to rectal prolapse. French prides itself on having le mot juste, the exact word for the specific thing. Frank Wynne, in his brilliant and faithful translation, matches this sometimes tortuous effort blow for blow, conveying the French original’s Adamic pleasure in naming.

While part two begins in summer with a communal washing scene and hay harvest, any hint of optimism is soon quashed: ‘Even the children seem only to remain children for the blink of an eye. They come into the world like livestock, scrabble in the dust in search of meagre sustenance, and die in miserable solitude.’

We are taken to the battlefields of World War I with Marcel, a distant cousin who comes to help on the farm, but first we experience war through the animals. Requisitioned from the farms, transported to the rear, they are butchered to feed the soldiers, who are themselves butchered by the war machine. On these killing fields, the paroxysm of depravity, indifference, and cruelty reaches biblical proportions, with comparisons to Gehenna and the fourth plague of Egypt. Micro-history meets world history with Marcel’s return, one of millions of gueules cassées, facially disfigured servicemen. His silent trauma is inflicted on Éléonore, who is powerless to protect their son, Henri, from his violent outbursts.

Nothing is in stasis; things morph from one state to another in a continuous cycle of growth, decline, putrefaction, death, and renewal. In the earlier sections, people dig wells in the earth with their bare hands and pigs forage for grubs in the layers of pigeon excrement and leaf litter; while in the latter, the telluric connection is lost, severed by concrete and a cocktail of industrial chemicals. By 1981 the smallholding is an industrial pork farm and the anus mundi that is the pig shed produces a ceaseless flow of fetid effluent. The fumes and sludge permeate the men’s skin and lungs, no matter how vigorously they scrub themselves, and seep into their waking dreams and sleeping nightmares, oozing in and out of every orifice. We join Henri (now in his sixties), his sons, and their complicated family which deals with its own set of traumas: alcoholism, physical and mental-health breakdowns, silence, incest, deceit.

After nearly three hundred pages of violence and misery, the comprehensive downfall of the final section, ‘The Collapse’, comes as a kind of relief, and the thread of animal–human metamorphosis, in the lineage of Franz Kafka and Marie Darrieussecq, reaches an intense culmination. Here, a level of personal anger pierces through Del Amo’s otherwise quiet voice. We are struck by the cycle’s nauseating senselessness; the toxic legacy of the chemical compensations devised to counteract the genetic deficiencies deliberately created in the pursuit of cheap meat.

It is difficult to compare the grim violence of the first half of the text with the depravity of the second, yet there is certainly a warning against any nostalgia for the bucolic life on the farms of yore. Animal and familial brutality are presented as umbilically linked, the violence of industrial farming embedded in ancestry, transmitted through some inescapable, atavistic magnetism.

Animalia, the first of Del Amo’s four novels to be published in English, continues a steady line of French literature of physical and existential disgust from Rabelais to Houellebecq. It is as magnificent as it is bleak: a sickening and strident alert. In a moment of lucidity, seeing his reflection in a pig’s pupil, Henri delivers an ominous warning: ‘The eye was in the tomb and stared at Cain.’ I wondered whether Animalia is about animals or humans, the body or the mind, our inner lives or our relationship with nature. It seems to be about all of these elements and how they are at once isolated and entwined, bound in language that searches to map and understand them through their complexity and exactitude.

Comments powered by CComment