- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wayward Memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Mortal Divide is an anti-oedipal odyssey, Joycean roman à clef, migrant memoir, and Orphic mini-epic. Nemerov’s self-reflexive Journal of a Fictive Life is one of its inspirations. George (Yiorgos) is a first-generation Greek translator working at the Multicultural Broadcasting Service. Victim of the media machine, he begins to hear and see things that aren’t ‘real’, including his spectral double Yiorgos Alexandroglou, and plunges videoleptically into dreams whenever he closes his eyes.

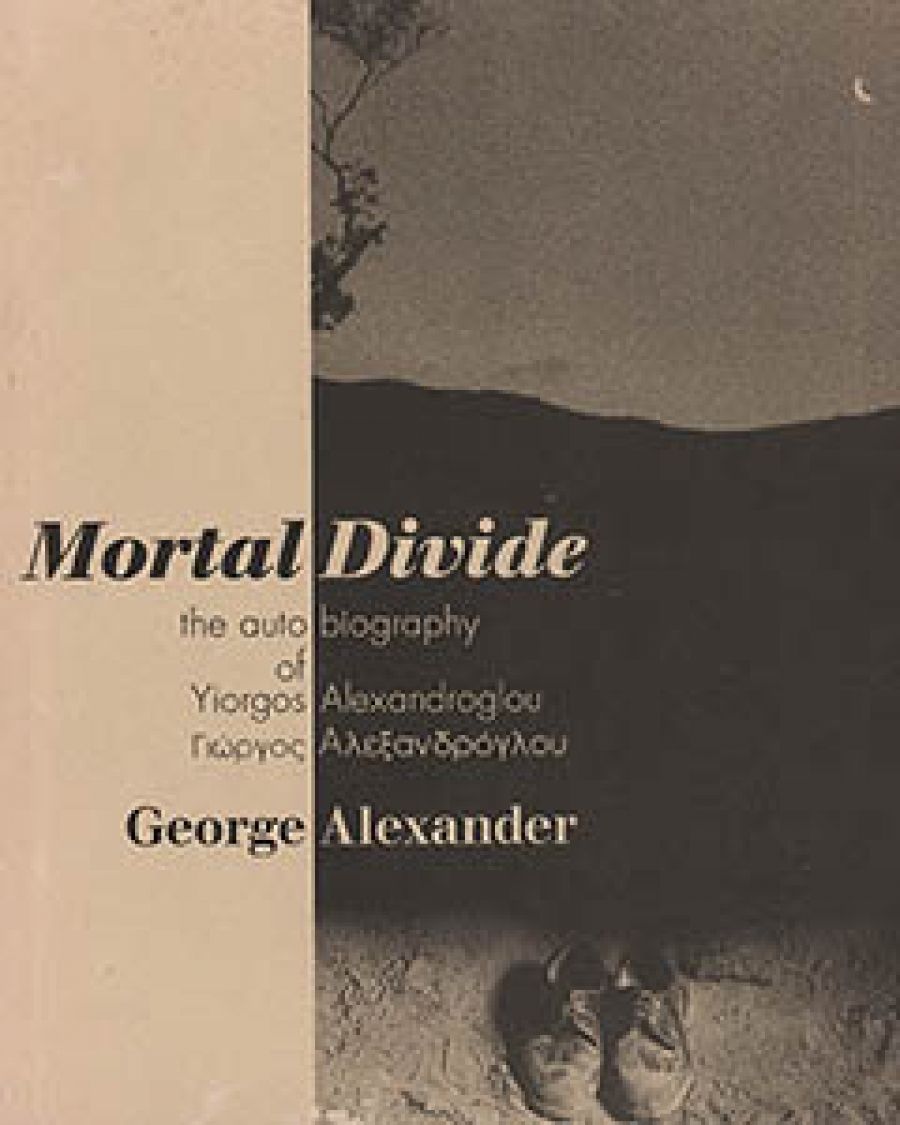

- Book 1 Title: Mortal Divide

- Book 1 Subtitle: The autobiography of Yiorgos Alexandroglou

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandl and Schlesinger $19.95pb, 192 pp

If he could grow up, he would, but George has escaped the Mediterranean boyhood tradition, ‘a time during which you become a man’ and the penis is mightier than the pen. Fearing that he is losing that ‘Arnold Schwarzenegger feeling – a hard-on everywhere’ – George’s marriage to Alys begins to fall apart, while Alys embarks on a relationship with Third Wave black-leather feminist artist Zoe, who also happens to be George’s ex-lover.

Mourning the death of his father, Kyrios, from whom he has inherited a package of memorabilia, George time warps to the rembetika bars of Perth, hence to Kastelloritsos, a Greek island off the coast of Anatolia, so small it never appeared on maps, an island on a ‘penumbral margin’ between competing cultures, the Turkish and the Greek:

In this arid bombed-out logos, Eros attempts to overcome Thanatos, and memory scraps together a history, despite the fact that no one remembers back further than forty-eight years. Seduced into his own erotic fantasy, George experiences an epiphany which (no surprise) ends with the mysterious death of the lover, thereby adding to George’s guilt about ‘rifling through her soul for erotic storytelling’. On trial is George’s ego, busily creating a dreamworld for his own transcendence.

On trial also is the Oedipal narrative, and the power of various other fathers: Seinfeldian figures of detective Belaqua Toth and a Freudian psychoanalyst, Dr Nemerov, are assigned to supply the glossary on the central narrative. Howard Nemerov, ‘Chicago MD, with a golf-pro hair fix and an asymmetrical Zorro moustache’, advises George to take the Writing Cure, fall into life rather than art, ‘normalise’ his relationship with his absent but heroic father, assume patriarchal responsibility. To my male-oriented taste, Mortal Divide charts a man’s mental breakdown with an appropriately self-obsessed thoroughness. But perhaps the story of Alys and Zoe could have had a few more pages to breathe. Some readers will feel that the women are too much the projection of a cuckhold’s paranoia: Zoe seems predatory, Alys seems manipulated. Perhaps Alexander’s dialogue falls short of embodying more complex creatures, but Mortal Divide is more than a social realist text, and George is very much the unreliable narrator.

The women seem real enough when Alexander writes the text, when he modulates from action and dialogue to interpretation, when the picture frame extends to larger psychological and social formations. Clearly, the critical interpretive text originates with the women who suffer the anti-hero. Alys, for example , is a significant anchor in the critique of Greek Machismo: from a ‘solid’ Anglo family, an impatient agent of (post-colonial) assimilation, a post-modern and cultural relativist who won’t indulge George’s paranoia and multi-cultural nostalgia: ‘Alys says forget about it [the Name]. The Name of the Bloody Father. Why undermine this Anglo power that could protect me? In Australia, she believes, no name is foreign.’

George believes that the Name ‘is the distance I must travel to make friends with myself’. George cannot ‘kill’ his double Yiorgos, but to reconstitute authenticity via memoir or an SBS documentary is itself a death of experience, and leaves the mind divided from the body.

Alys’s advice helps George to redeem himself. It is her home George dreams of returning to, of finding a path back to. But the cure for George’s ideological mindset is both travel (departure and arrival) and writing (recovery of experience from the flux). Writing letters home to his daughter Toto in Bondi, George comes to terms with the beauty of the ‘domestic cage’ he has left. The father-daughter relationship is beautifully told. The nostalgic modernist fathers the naive post-modernist channel-surfing for the next coolest thing, angling Dad for more RAM. She is the child who fathers the man, keeping contact with George while he is overseas, his absence redeemed by modern communications.

Toto inherits her mother’s strength, escapes her Greek grandmother’s victim role as abandoned wife and migrant and, above all, breaks the misery of family inheritance; she is the shining hope that Larkin was wrong when he wrote ‘They fuck you up, your Mum and Dad’.

Mortal Divide investigates the process whereby a mind ‘dreams himself into a man’ and realises Pasolini’s belief that ‘the real truth is never in one dream, but several’, an autobiography’s multi-faceted telling of many stories. George’s roots go so far back, and have no clear narrative source, can never ‘start’, so what emerges is a miniaturised scrapbook of relatives: the mother, the step-father, and the grandfather George is named after. Time and place is telescoped, chaotic, and ambiguous: Greek, Egyptian, Turkish, Italian, nationless, anarchic. Between the absent father and the son, myth and projected desire plug the gap in a broken narrative, and variegated truth pulls it apart again.

Morphing through ‘witness’ positions in what Deleuze and Guattari describe as a schizoidal culture, this book is a Cultural Studies essay of omnivorous proportions. Quicker than the particle transporter in Star Trek. Elsewhere is everywhere: Bondi Beach is suddenly Port Said, Cottesloe is Cairo. The world-theatre is diasporic, where we can be taxi drivers by day, Greek gods by night. Alexander writes that ‘those that left the village merely shifted and relocated its borders’. Kyriakos is the cook and the gambler who embodies the multicultural fruit-salad pizza. His migrant English becomes ‘Mangluage’. The ‘original and best’ pizza is a lost recipe, Modernism is haute cuisine, and ‘Food is the nation’s petri dish’.

Sad and magical at the same time, constantly reflecting on its own significance from a hundred wave-inflected angles at once, raki-sodden with pathos and a late Byzantine morbidity, George’s meditative search for one’s ancestors and author(ity) figures is doomed: for once Dad’s found the Ur-text, it dissolves back into ‘digital diversity’, where experience is rationed and packaged, and no cultural tradition valorises any other. Nevertheless, George’s ethnic other refuses to be commodified, turned into kitchen-kitsch, or killed off (assimilated).

The value of Mortal Divide is in its bold pace, visual density, and dignified humour. The book’s zero degree of reality consists of an intimate cosmopolitan ideal, with familiar domesticities. Far from ‘falling into art’ too solipsistically, the Gypsy and the family man, husband and wife, the physical and the theoretical (the Second Language), child and parent, negotiate the middle ground. Mortal Divide is ‘autofiction’ without narcissism. The text is beautifully complemented by Peter Lyssiotis’ mesmeric photo-montage.

Comments powered by CComment