- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Part guru, part factoid, Gough Whitlam shows every sign of enjoying his retirement from politics. Thanks primarily to Sir John Kerr, Sir Garfield Barwick, and Sir Anthony Mason. And of course, Malcolm Fraser.

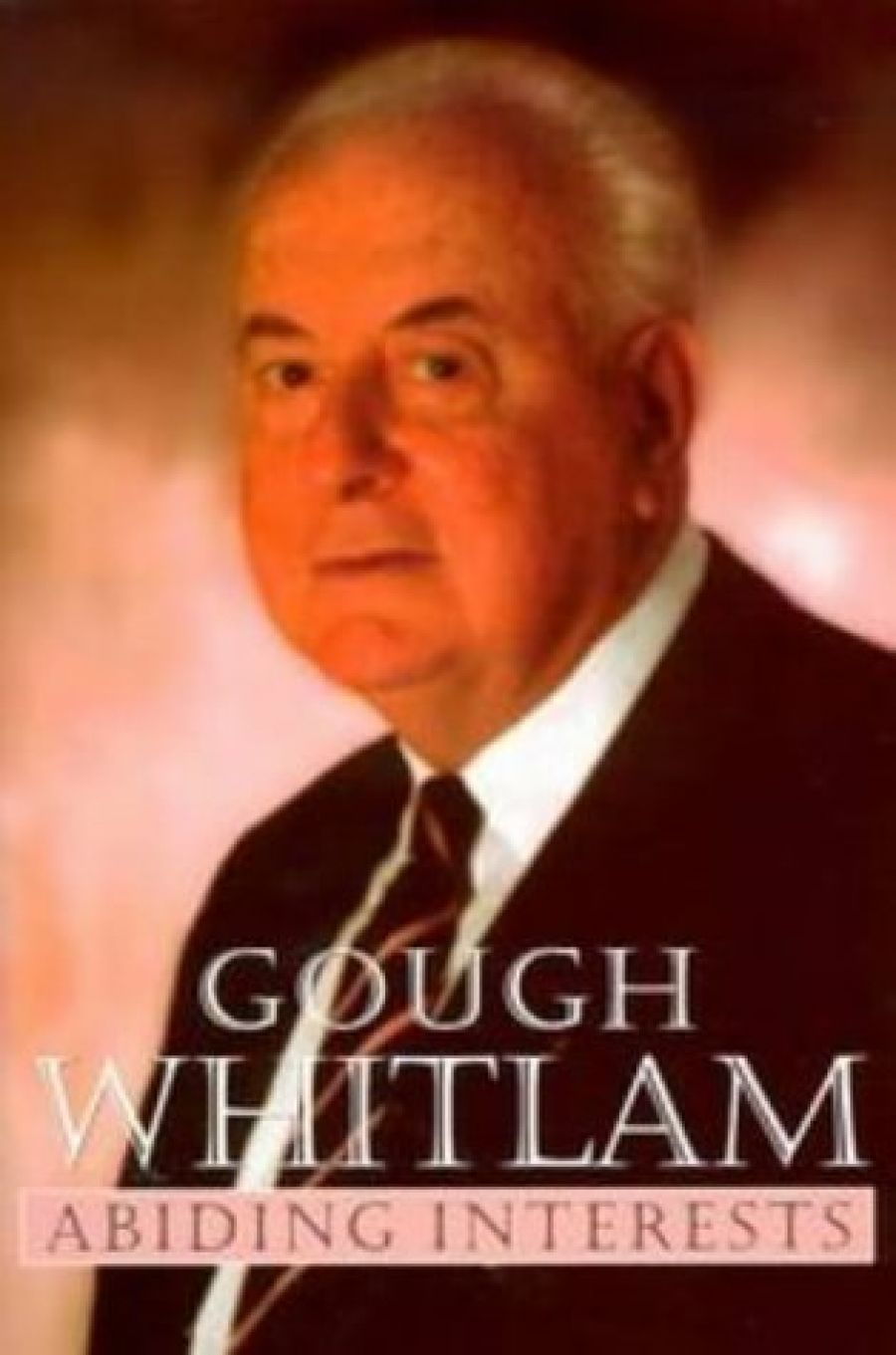

- Book 1 Title: Abiding Interests

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $29.95 pb, 339 pp

Former Governor-General John Kerr and former High Court chief justice Garfield Barwick get a working-over in Gough Whitlam’s Abiding Interests. However the ‘third man’ – former High Court judge and later chief justice Anthony Mason – escapes criticism.

At age eighty-one, Gough Whitlam is still maintaining the rage against those he blames for the dismissal of his Labor Government on 11 November 1975. The initial – and most significant – chapters of Abiding Interests are devoted to a ‘review of’ and ‘clues to’ what the former prime minister terms ‘the coup’ of November 1975.

In referring to a ‘coup’, Whitlam has in mind Kerr’s decision to dismiss his government on 11 November after receiving advice from Barwick. Abiding Interests contains no references to the CIA or MI6. Whitlam still alleges improper practice on the part of Kerr and Barwick – but not Mason (who also provided advice to Kerr). However, Whitlam is not into conspiracy theories, so beloved by the likes of John Pilger.

To the author, the constitutional crisis of 1975 was sparked and resolved (wrongly in his view) by Australians.

In Abiding Interests, Whitlam re-states his familiar position that ‘in 1975 the Senate did not reject the budget; it simply refused to vote it up or vote it down, or vote upon it at all’ and that ‘the entire contest of October–November 1975 was about which side would retreat from its chosen ground’.

The central argument in the first fifty pages of Abiding Interests is that by 11 November 1975 ‘at least four Liberal senators were on the verge of voting to end the political crisis’ and that ‘in 1995 for the first time, two of them went on the public record to say so’. He names names – Eric Bessell (Tasmania), Thomas Drake-Brockman (Western Australia), Condor Laucke (South Australia) and John Marriott (Tasmania). In coming to this conclusion, Whitlam relies heavily on Paul Kelly’s November 1975 (1995). However, like Kelly, Whitlam comes to judgment by ignoring important evidence. Victorian Liberal Alan Missen was the senator most uncomfortable with Malcolm Fraser’s decision to block supply. In writing Alan Missen: Liberal Pilgrim, Anton Hermann had access to the late senator’s personal diary. In 1975, Missen reflected that he had no intention of crossing the floor to vote against the Coalition and pass supply unless a solid core of colleagues were prepared to support him. In a contemporaneous diary note, he wrote that ‘nobody’ would do so. As we know, hindsight changes perspectives – even about courage.

Using as his source Bill Hayden’s autobiography, Whitlam writes that at 10am on the morning of the dismissal, Kerr phoned Fraser ‘and stipulated the conditions on which he would make him Prime Minister’. Neither Kerr nor Fraser has denied that this conversation took place, but they differed as to what was said.

Gough Whitlam, citing Bill Hayden, accepts Malcolm Fraser’s (belated) acknowledgment that he knew in advance that the dismissal was likely. But, once again, this ignores the evidence of David Smith (as told to Paul Kelly) and Bob Ellicott (as told to me). Smith (Kerr’s official secretary) was in the Governor-General’s office when the conversation took place and Ellicott (then shadow Attorney General) was with Fraser when Kerr’s call was made.

As the author points out in the foreword, his current abiding interests extend beyond the events of November 1975. There is material aplenty on UNESCO, heritage and environment, health and national infrastructure. All are areas in which Gough Whitlam has been personally involved – either as activist or commentator – since his resignation from the House of Representatives in July 1978.

Abiding Interests is a significant achievement especially for an octogenarian. The book explains why the author has attained his guru status among both the ‘maintain the rage’ club of circa 1975 and young Australians alike. And there is much material to please many a factoid. For example, the Queen’s one-time private secretary is referred to as ‘Sir William Heseltine PC (1986), GCB (1990), GCVO (1989), AC (1988), BA(WA)’. Have facts, will cite.

Had the dismissal not occurred, a federal election would have been held in late 1976 or early 1977. It’s likely that Gough Whitlam would have led Labor to a heavy loss of the kind that occurred in December 1975 and again two years later. Due to Kerr’s decision, Gough Whitlam left the Lodge as a martyr – of the political kind.

Gough Whitlam’s current guru status depends substantially on his perceived role as a political victim. In other words, his prestige is an unintended consequence of Kerr’s decision (as advised by Barwick and Mason) of almost a quarter of a century ago. Read all about it in Abiding Interests – brought to you by courtesy of the dismissal.

Comments powered by CComment