- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1992, Fang Xiangshu collaborated with Trevor Hay, a mandarin-speaking Melbourne academic, on a non-fiction book, East Wind, West Wind, an account of Fang’s escape from China to begin a new life in Australia.

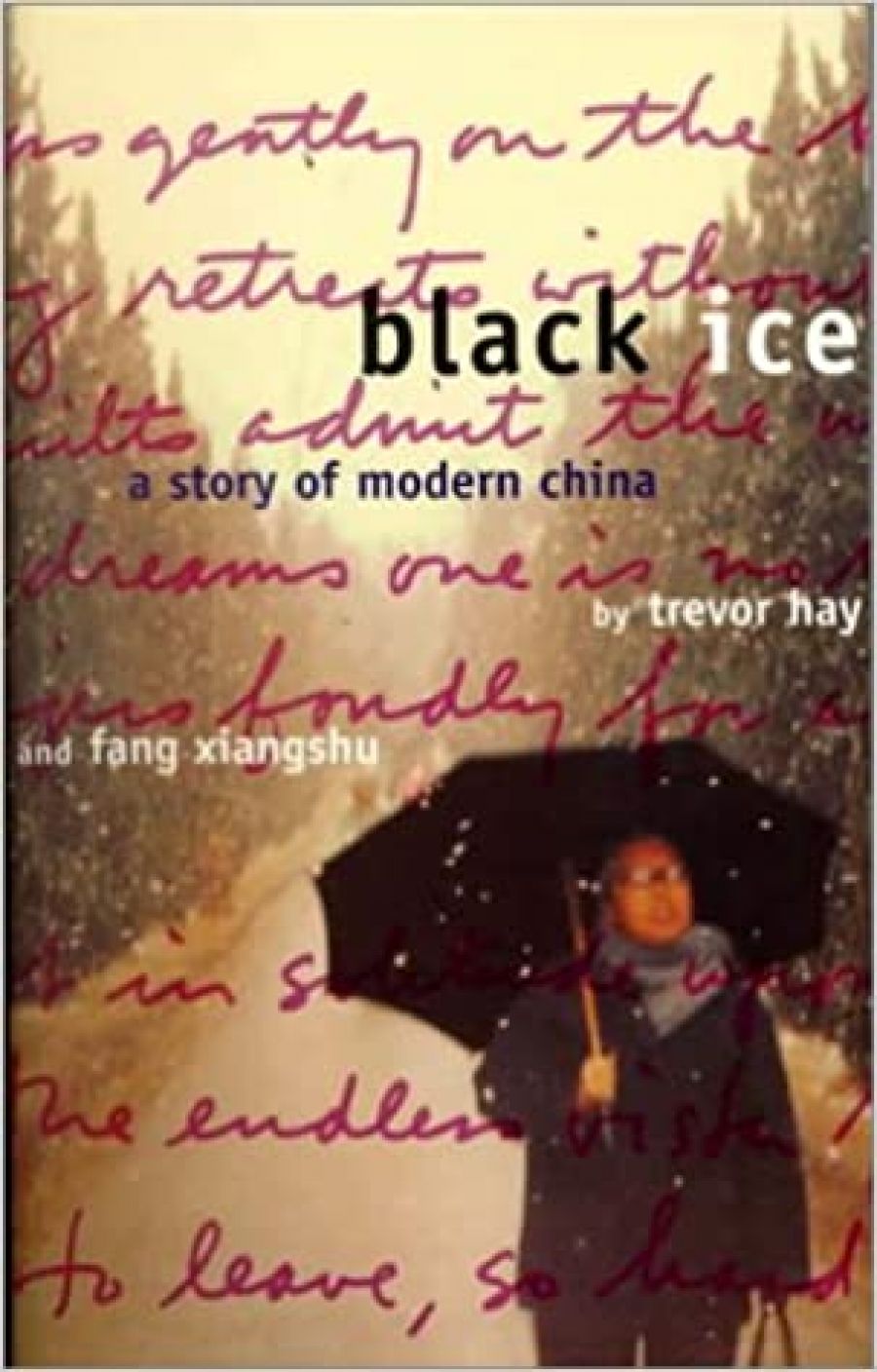

- Book 1 Title: Black Ice

- Book 1 Subtitle: A story of modern China

- Book 1 Biblio: Indra Publishing, $18.95 pb, 182 pp

East Wind, West Wind was a fascinating book for more than one reason. It showed that the sort of tactics used to break people’s spirits during the Cultural Revolution were still being used in the allegedly more open society of the 1980s, and it also gave a first-hand account of how it felt to be a teenager (Fang was born in 1953) in the time of the Red Guard terror.

Fang was no hero. He was so afraid that at age fourteen or fifteen all his fair fell out, and this, together with his ‘bad’ family background made him a target for mockery and beatings. His father was declared an enemy agent and sent to labour camp, his mother was declared ‘the imperialist running dog’s stinking daughter’, and Fang, like other school children, was forced regularly to denounce his parents for ‘spreading poison.’

East Wind, West Wind was powerful, bluntly written, sometimes clumsy, but none the worse for that, though inevitably it never achieved the popular success of Wild Swans, a product so carefully polished, packaged, and promoted.

Now Fang, again in collaboration with Trevor Hay has recycled some of his material in a novel, Black Ice. Rather mysteriously, Hay is listed as first author and Fang second, instead of the other way round as in their previous collaboration, but the story line is, one supposes, largely Fang’s. Until she changes it to her nom de guerre, his heroine has Fang’s mother’s name Fang Wen, and he dedicates the book to his mother, because she ‘always wanted a name like Black Ice’.

The novel covers something over sixty years in Fang Wen’s life, most of it lived under the revolutionary name Mo Bing, Black Ice ‘a name that demanded respect, perhaps even fear, so different from ‘Jade Cloud’, or ‘Fragrant Orchid’.

Fang and Hay create Mo Bing as a young Communist cadre, working as an undercover agent in Shanghai in the last years of the civil war. Her life then follows a familiar but always engrossing pattern, mirroring the ups and downs of the Chinese state itself: a decade or more of idealistic and dedicated work following the declaration of the People’s Republic in 1949, hints of things to come in the Hundred Flowers campaign, the frightful years of the Cultural Revolution when Mo Bing, ardent worker for the Revolution becomes an enemy of the people and is denounced by her own son; rehabilitation, disillusionment, old age, her whole life ‘an unused piece, a fragment left over from the time the gods had tried to repair a hole in the sky’. The authors say the work is not a translation, or a memoir or biography: ‘This is a novel conceived and written in English, rediscovering for English literature authentic Chinese cultural and linguistic forms.’ It is a style a little unaccustomed, a little awkward sometimes to western eyes, but with a great feeling of authenticity, and graced often with poems, from the classical to the revolutionary.

The Cultural Revolution scenes, a time when the nation’s young were seized with some sort of collective madness, are sickeningly familiar. Where the book does break new ground for most foreign readers is in its accounts, brief but deeply interesting, of the undercover work done by Communist cadres in the mid forties; the scenes of village life, coarse jokes and all; and in particular, the little known struggles between Nationalist and Communist factions in camps for Chinese prisoners-of-war during the Korean war.

The Chinese Volunteer Army (so-called) fighting in Korea was theoretically made up of dedicated young Communists. In fact, Nationalist sentiment among the prisoners was still running strong, and in the camp in which Mo Bing’s husband, Li Nanting, found himself (the novel is also his story) bloody clashes took place between those who wanted to take up the American offer of going to Taiwan, and those who insisted on repatriation to China. Chinese killed Chinese, with the utmost barbarity, with the Nationalist faction dominant. Li Nanting and other prisoners who wanted to go back to China were given a lesson in what might happen if they persisted in their obduracy. After one night of bloodshed, the prisoners were taken to a tent and ‘each in turn was made to halt before a trestle table on which stood a bloodied basin containing three hearts for the motherland’.

Black Ice is an uncomfortable read and a salutary one. It is a useful addition to the literature about China which, one hopes, is dispelling some of the extraordinarily simplistic and romantic views of earlier years.

Comments powered by CComment