- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Merarra is the local name for the land near Walcott Inlet in the far north-west region of Western Australia where saltwater meets freshwater, coastland meets inland. And the ‘man from Merarra’ was the last ‘full’ speaker of the local, Unggumi language, a senior lawman and famous Kimberley stockman called Billy Munro, or, in his native tongue, Morndi.

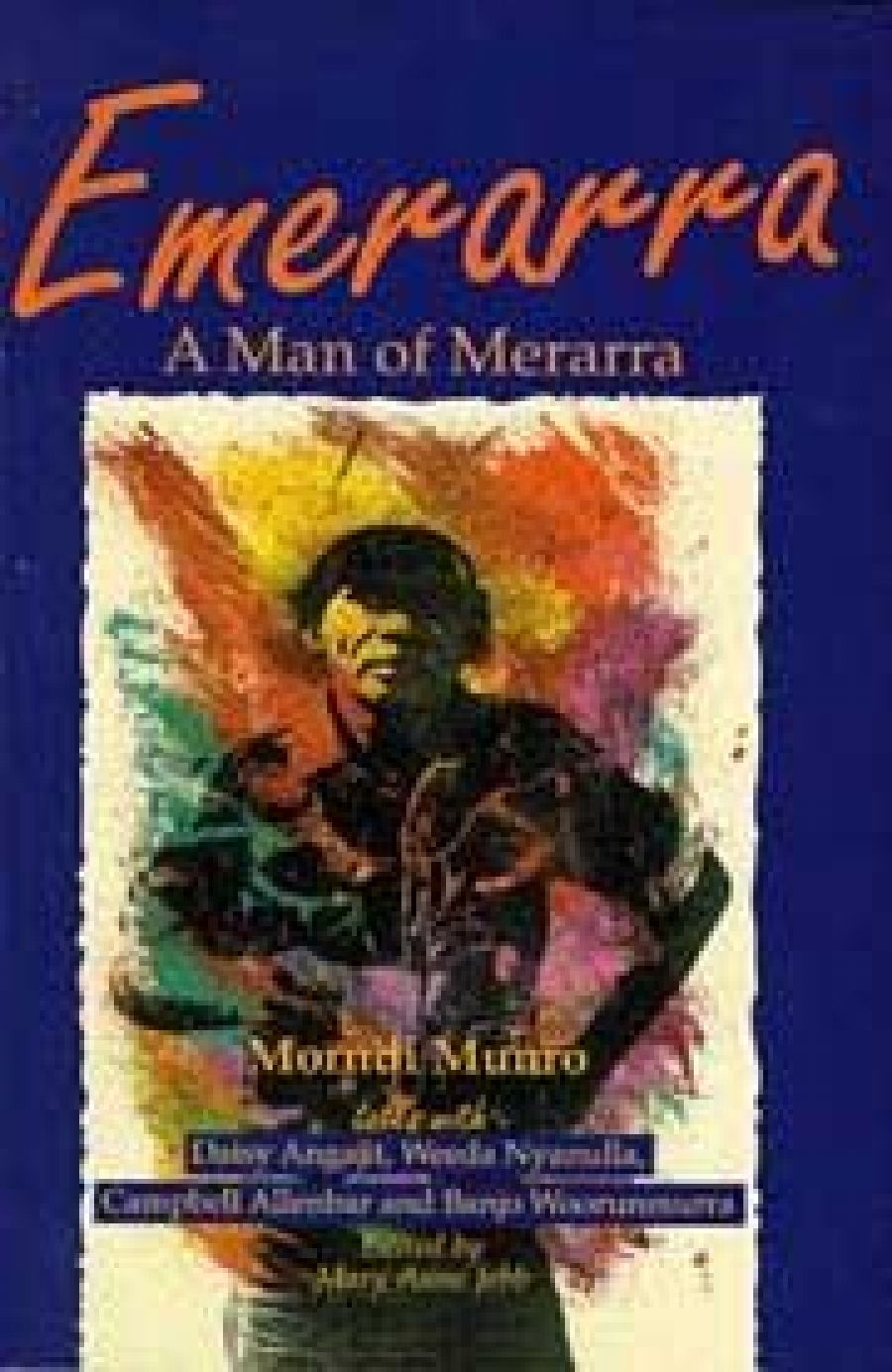

- Book 1 Title: Emerarra

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Man of Merarra

- Book 1 Biblio: Magabala Books $16.95 pb, 201 pp

Magabala Books of Broome, the people who brought you My Own Sweet Time by Wanda Koolmatrie, who was neither female nor a Koolmatrie, but nevertheless succeeded in being shortlisted for the 1995 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, and given the Dobbie Award in 1996 for the best book by a woman, have, with Morndi’s story, at last published a genuine and readable biography from the North Kimberley.

The voice is authentically that of Morndi himself, as I can attest, having, as his lawyer in a common law claim to title to land, spent many hours with him in the last few weeks of his life, in early 1993, when I first read this history. Morndi had given me the manuscript, assembled by Mary Anne Jebb, from the tapes she made of Morndi’s talks with her and with others, also former clients of mine, whose names appear on the title page as collaborators in the authorship of this book.

Because of the respiratory disease which was killing him, Morndi chose to instruct me by taking me from the facts contained in the manuscript, to the tapes, to further talks between solicitor and client, in order to save his breath. Dependent on an oxygen tank which stood by his bed in his nearempty house on the edge of the marsh in Derby, he would ask me to visit him several times a day: ‘We talk little bit now – little bit later’. In between times he would try to rest. His breath came with agonising difficulty, and our sessions were punctuated by coughing spasms, which caused me to make frequent trips to the bathroom to empty pots full of phlegm he expectorated. His courage and determination brought tears to my eyes, even as my guts turned over – to use his expression.

I declare this interest in order to explain my views on the book, which are that, as far as it goes, and with some reservations, for example about the editorial comment on the lawman’s use of the term ‘tribe’, Jebb sides with anthropological use without explanation or justification, contradicting Morndi, it is an excellent Kimberley history.

In February 1993 Morndi sent me to find Mary Anne Jebb so that by listening to the tapes she held – the ‘project’ had been funded by an Australia Council grant – I might catch up faster on his life-story, and spare his breath. The purpose of this was that we would produce the affidavit to be used as evidence in court to prove Morndi’s title to land – a sworn document, admissible even after his death.

I found Mary Anne Jebb in Fremantle on 1 March 1993, but I did not succeed in getting access to my client’s tapes. ‘There are more and more ways of owning information,’ said Jebb. This refusal produced an unexpected effect – as it forced me back into Morndi’s company in a race against time.

Morndi died in mid-April 1993. According to Jebb, grieving relatives withheld his book from publication until 1997. Now it has appeared, it is instructive to read Jebb’s ‘Afterword’ and ‘Background notes’, particularly on the subject of ‘editorial intervention’ and the editor’s task of selection. It begs the question of what happened to the tapes. Where, now, is the rest of the material that was denied Morndi’s lawyer and gathered under the auspices of an Australia Council grant as part of a social history? Jebb writes: ‘there is a great deal that we said and not included, and even more that is known and not said for many reasons.’ There is, for example, no mention in the Afterword, of the last great drama of Morndi’s life – his participation in the Kimberley land claim in 1993.

Of the four ‘trustees’ of the Morndi biography project, that is, the controllers of the use to be made of the tapes, two are former clients of mine – plaintiffs in the land claim – and one of those two is Morndi’s ‘son’ who brought me a copy of the manuscript in early 1993. But two, who are persons without standing to claim land in their own right, are members of the Kimberley Land Council, the organisation which, fully-funded while the plaintiffs were unfunded, launched an attack on the land claim of the Kimberley elders between 1992 and 1994. That is, the ‘trustees’ of Morndi’s literary estate were members of a group opposing him in the courts, and controlling the use of information he had provided.

I tell this story to demonstrate two things: one, that as far as it goes this is a fascinating personal history – accurate, direct, and terrifyingly vivid. The other, that it is a carefully edited history, from which certain key information has been deliberately omitted. As far as it goes, and provided that readers are aware of this fact, these questions about control of intellectual property do not detract from this biography of a spirited Australian, but merely add to its fascination.

Comments powered by CComment