- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

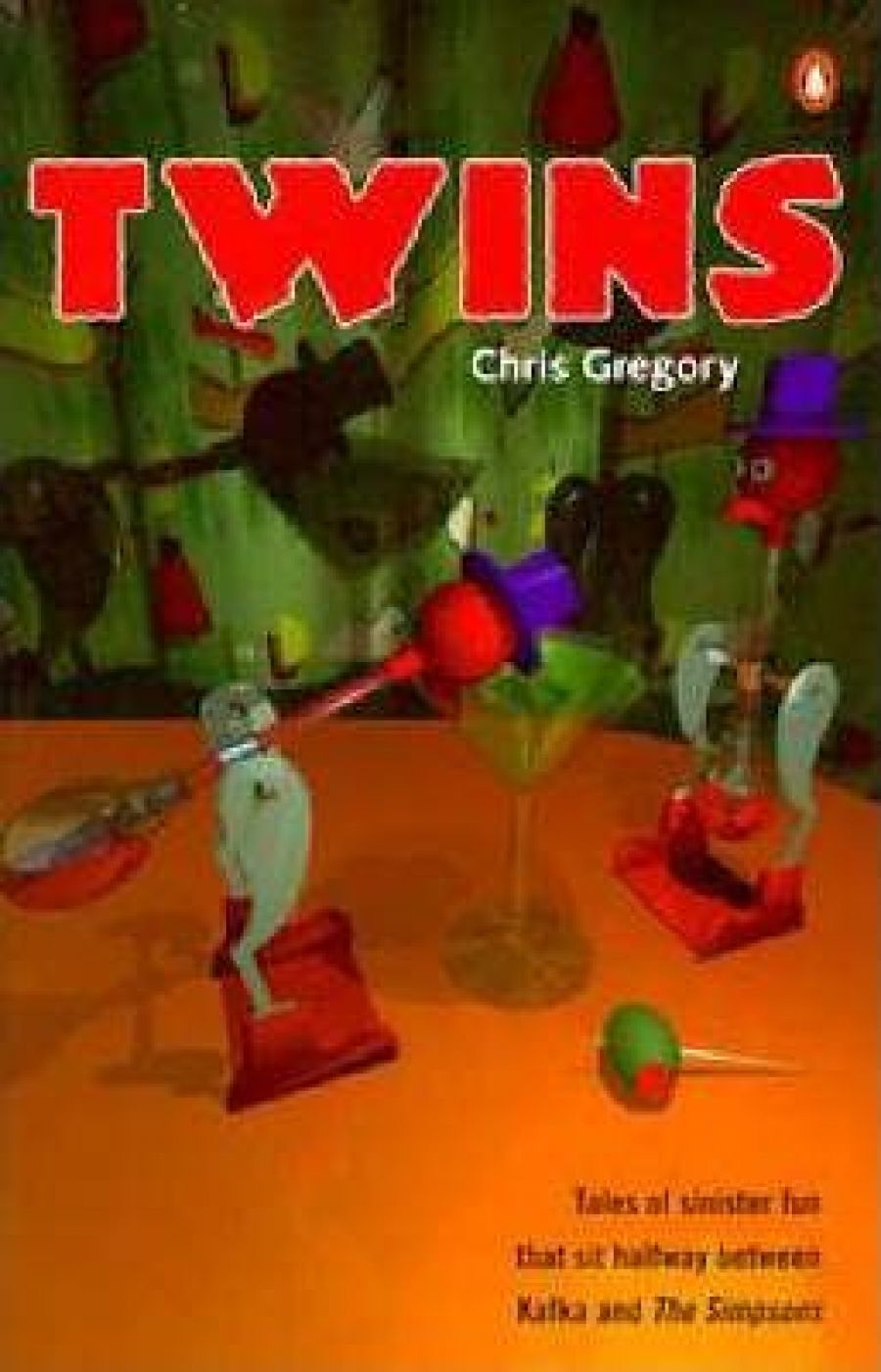

Incorporating photographs, diagrams, idiosyncratic typography, and even a list of references, Chris Gregory’s Twins is a media kit as much as a short story collection. It beings with a kind of parable about reading:

- Book 1 Title: Twins

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin $16.95 pb, 272 pp

Is this an admission of disappointment, with both novels and the adult world? If it is, the blankly ironic tone prevents us from taking it too seriously – it seems to suggest that beyond ‘adult realities’ and the character-driven conventions of novelistic fiction is a more interesting world, anyway. By exchanging the tight, tailored form of the modern short story for a looser combination of observation, narrative and cultural references, Twins seeks to introduce us to this world.

The early part of the collection finds Gregory compulsively, if comically, undermining himself. ‘Mabel Ambrose’s Head’ is a mock-historical crime story, interspersed with absurdist details that move us abruptly from the nineteenth century to the present-day: a servant girl character reappears as an actor on Chances, ‘the first woman to give birth to a fruit bat on national television’. Trying to imagine Australia’s fist inhabitants in the story ‘Mock Chicken’, with Gregory’s narrator ends up with ‘people much like myself, with similar preferences and tastes’. He confesses that the ancient Australian landscape he describes ‘owes more to my memories of the landscape of cartoons than to anything I have read on the subject of Australia during the Pleistocene epoch’. Wittily parading his ignorance, and rendering history as disembodied fact or mythic cartoon, Gregory moves toward the great mean of postmodern style: humorous banality. This produces some deft observations – ‘The chicken is an elegant and highly sophisticated piece of modern technology’ – but a gradual sense of malnourishment in the reader. Inane parody is undoubtedly a valid, even faithful response to contemporary world, but don’t readers nevertheless deserve more than disconnected ‘explorations’ of televisual subjectivity?

Fortunately, the story ‘Teratology’ makes a great leap forward. It concerns Siamese twins, with one twin telling of his feelings of resentment and envy towards his other half, a well-endowed simpleton. The divided body of the twins is a kind of mocking stand-in for that staple of existential dilemmas, the divided consciousness. ‘We really have very little in common,’ we are told, just after the details of their mutual masturbation contract are disclosed. Their conjunction enforces a strange intimacy, and comically reflects a masculinity in conflict. As the simple twin plays with his ‘friends’, a collection of deformed Barbie dolls, the other gives himself over to proud, isolated self-analysis, though his monologue cannot help but return compulsively to the fact of their uneasy co-existence.

Teratology is defined as the study of monstrosities, and it is indeed a form of teratology that underlies Gregory’s humorous focus on banality. His stories twin the banal with the monstrous, as though they belong to each other like Siamese twins. Of course, banality is itself often monstrous, as the most mundane consumer items – like the aforementioned chicken – can testify. Thus the role of teratologist provides Gregory with a mission, and ‘the Cold War, cheese, Godzilla, piano lessons, shopping centres, [and] Walt Disney’ all prove worthy subjects for teratological investigation.

Some of Gregory’s best pieces deal with the inner child, or rather its monstrous twin, the Id. ‘The 5000 fingers of Dr T’ recollects a childhood spent watching monster movies, and their formative effects:

I thought that the television should look after me, or at least take on some responsibility for my upbringing, and in many ways it did ... My parents had their own plans for my future. All I wanted to be was the guy who wore the Godzilla suit and got to stomp all over a miniature Tokyo.

This aspiration is realised to an extent in a later story, ‘Salaryman’, which describes working as a graphic designer in an advertising firm. The frustrations of the position, with its

‘nominally creative behaviour’ lead to hilarious attempts to reveal his bosses ‘as they truly are, as the parasitic rulers of a city built from sacrificed flesh’. With this story and the final one, ‘Jackie Chan,’ Gregory seems to find his style: simple narrative that uses a web of associations to develop oblique, complex apprehensions. The chimerical Jackie Chan gives rise to a meditation on the narrator’s feelings for this virtuosic and global figure; through this meditation the story seeks in sly fashion to fit together the local and the global. It seems an appropriate aspiration with which to close the collection, which explores a fragile yet ubiquitous sensibility, that of the child-like urban consumer and flâneur.

Comments powered by CComment