- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Playwright and professional poéte maudit, Barry Dickins launched this collection as part of La Mama’s thirtieth anniversary festivities. Dickins, it is reported, was not in a festive mood. In an unusually begrudging and self-absorbed frame of mind, he allegedly failed to extol the selected plays and went so far as to hint that one of his own tautly sprung specimens should have been included.

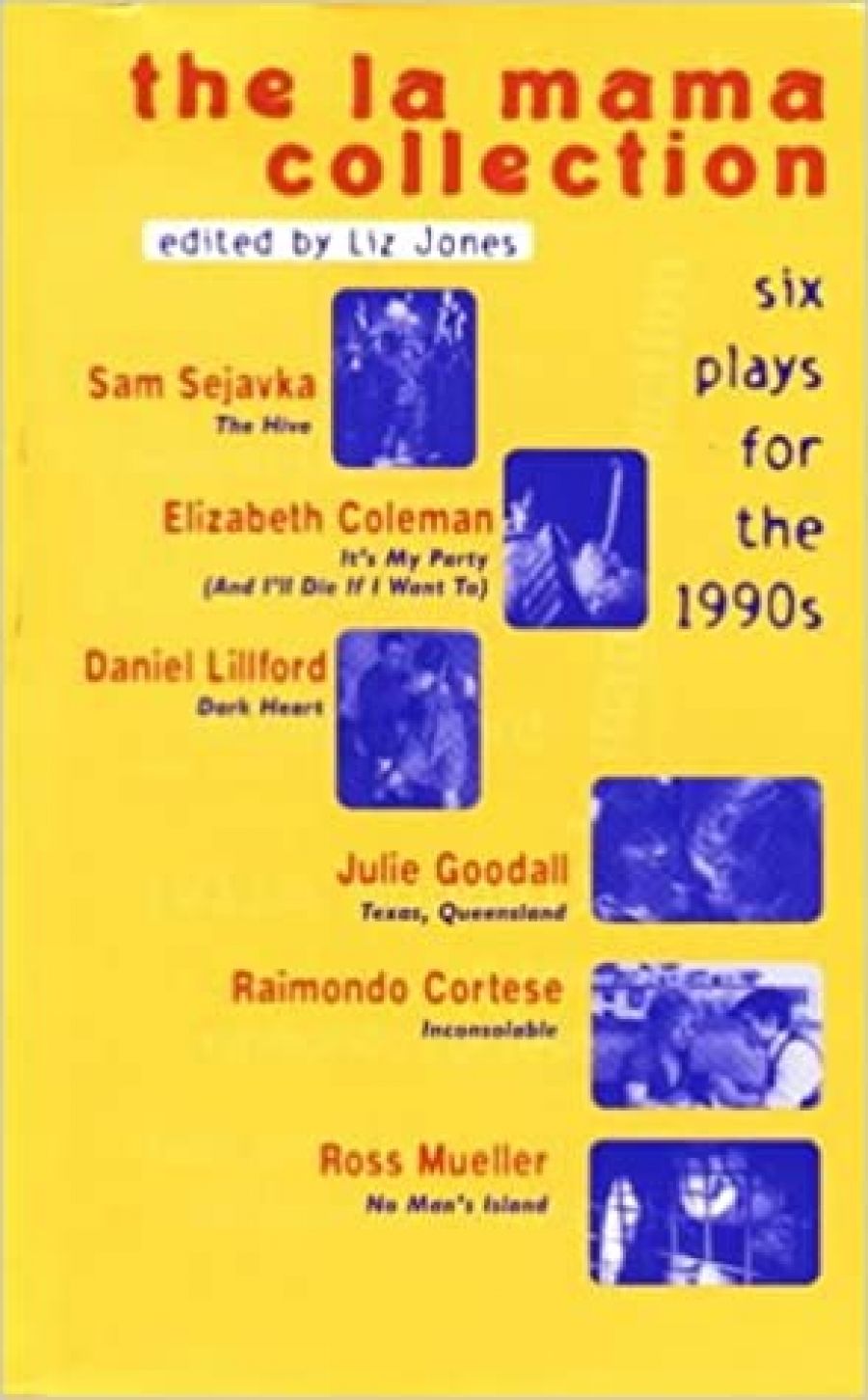

- Book 1 Title: The La Mama Collection

- Book 1 Subtitle: Six plays for the 1990s

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency Press, $21.99 pb, 310 pp

None of these remarks stems from an elder’s envy and churlishness. Much worse than ‘ageism’ (which it entails), neophilia embraces, and is in part dependent on, cultural and intellectual amnesia. As such this strong phenomenon has a non-cultural and anti-intellectual dimension, relying entirely on self-invention and instantaneity.

Neophilia enjoys intimate links with (and most likely is one manifestation of) the vast technological changes over the last few decades which have altered our perceptions of time and space, as part of a process labelled ‘postmodernity’. David Harvey, in his excellent The Condition of Postmodernity sees the postmodern as a temporal loop in the lunatic march of contemporary capitalism.

Mark Davis’ argument in Gangland that Australian cultural life is ruled over by a mafia of elders most certainly does not hold true m the theatre. I would argue that our theatre is in the grip of a paedomania or an amour juvénile, and that this is holding back the stage arts. Amnesia equals ignorance: ignorance of international and local tradition, imperviousness to classical and modern dramatic literature.

All writers, all artists, require an informed sceptical milieu, avenues of perspective, within which they can develop their art hand in hand with their self-critical faculties. Neophilia can canonise callow aspirants, can seduce them into thinking they have shot straight from the head of Zeus. I believe serious damage could be inflicted on a whole generation of writers, not only in the theatre. By propelling half-developed artists to stardom, the media and publishing houses are tempting fates in a philistine and meretricious fashion. However, such is the headless gullibility of our public and the despotic power of promotion, many of these half-talented ‘stars’ will remain ‘stars’.

The day I commenced writing this review The Age’s ‘Metro Arts’ featured a large article-interview with the new playwright Tony McNamara which accepted his instant stardom and built upon it, thus deliberately manufacturing a glittering commodity. The confection of instant stardom satisfies the most pathetic cravings of the public and media (vicarious fame and increased earnings) and is moreover at one with the craven Americanisation of Australia.

There is no evidence so far in McNamara’s modest achievements to warrant such a lofty elevation. His play The John Wayne Principle, recently seen, is exceedingly clever, fairly funny, but empty. It lacks a moral axis and trivialises some of the most sobering issues of our time by letting avaricious baboons off the hook.

The easy laughter and huge final applause with which the theatre’s middle-class patrons rewarded McNamara’s passionless nihilism and chic cynicism filled me with a double despair: the audience had fallen for the ‘star’ hoax, and they too lacked a moral axis.

The point of all this is this: it takes an individual of abnormal character to grow as an artist through uncritical fawnings. I hope very much Tony McNamara is one of these. The reviews of his play, including those in The Age, I should add have largely been critical.

Now to the plays – with the exception of Sam Sejavka’s The Hive, all of them possess a naturalistic style, hence conforming to the prevailing Edwardian idioms of much Australian theatre. To its credit The Hive demands dynamic staging, transformational ensemble acting and surreal soundscapes, but regrettably, for me, devotes itself to the vapid English doggerel writer, Rupert Brooke, for whom even this play cannot raise an iota of interest.

It’s My Party (And I’ll Die If Want To) sees Elizabeth Coleman having a good stab at gallows humour. The idea of a father, about to die suddenly, summoning all his family together for a final pow-wow is a sound one, but defeated by stock characters remaining stock to the end, despite revelations of a single daughter’s pregnancy and a son’s gaydom.

Daniel Lillford’s Dark Heart is a kidnap-ransom drama whose tensions too readily devolve into melodrama – by which I mean that the emotional steam generated by language is out of all proportion to the depicted action. As well Lillford has difficulty controlling words and accent and tone. Characters veer irregularly from American to Australian to Irish in their speech and behaviour, rendering them neither credible nor incredible.

Texas, Queensland, Julie Goodall’s effort, is, I fear, melodramatic, set in peanut country, and redolent of Louis Esson, Henrietta Drake-Brockman and other pioneers. Instead of dead timber, or gibbers, we have craters. The mother in this one yearns for a long-lost illegitimate daughter, and her single daughter is once again preggers.

Raimondo Cortese’s Inconsolable features two dismal yuppies circling one another tentatively, existentially, over cups of caffe latte and cigarettes. I could find very little drama in this, but lashings of sensibility.

Finally, we come to the No Man’s Island of Ross Mueller, a prison play which must have come up splendidly in production as it has been much praised. For me it sat confined to the page, again melodramatic, stock in its simmering homoeroticism and themes of paternal brutishness and lost sons. I imagine the production injected more humour than is evident here. Apart from a soupçon of Foucault, this play makes no advances on those of Jim McNeill and other cellular playwrights. When finished, I wondered where were the worlds of Kafka, Genet, Arrabel, or that of Robert Hughes’ The Fatal Shore?

In their inferior moments these plays display immunities to the most theatrical in the dramatic literature to tradition and crucially, to modernism: elements of the amnesia of neophilia.

An underlying naivety pervades the works. It’s as if the writers were starting from scratch. And in a sense, they are. The neophiliacs of today might well become the necrophiliacs of tomorrow.

With robust pruning, the avoidance of sentimentality and steaminess in production values, these plays would come up adequately on stage. Nevertheless, they do embody a sad retreat from the dramaturgical sophistication and playfulness of the 1970s: of which recent tradition the playwrights seem recklessly or solipsistically oblivious.

In opting for the youngish and new Liz Jones has been true to the presiding forces in Australian theatre society, and her choice seems admirably representative of what this tide and surf is throwing up. I don’t see what else she could have done: all else at the moment languishes peripherally.

Comments powered by CComment