- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

This eccentric, laborious book is designed to correct what most of us think about the 1967 Referendum. The popular belief – the authors call it a myth – is that the Australian people then voted to acknowledge citizenship by giving Aborigines the vote, and that this was a Commonwealth thrust towards, crucial, deeper involvement in Aboriginal affairs.

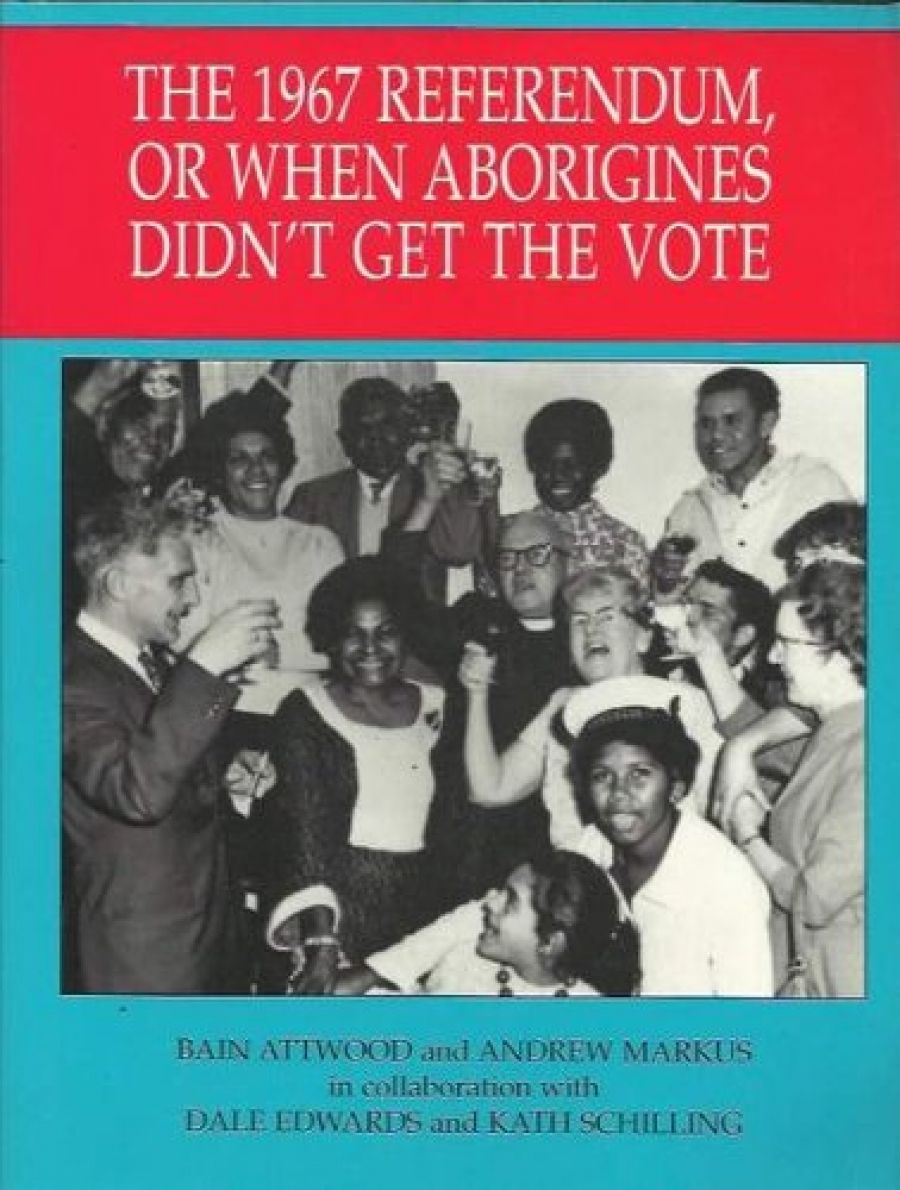

- Book 1 Title: The 1967 Referendum, or When the Aborigines Didn’t Get the Vote

- Book 1 Biblio: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, $25.00 pb, 154 pp

First, Aborigines were always Australian citizens simply by virtue of being born on this continent and coming under the Nationality and Citizenship Act. The Minister for Territories Paul Hasluck pointed this out to the anti-slavery campaigner Jessie Street in 1959. Hasluck went on: ‘But to ascertain what rights Australian citizens, including aborigines, have and to what disabilities they are subject, it is necessary to look at the general law.’

Secondly, the general law varies from state to state, which is to say that in some states Aborigines had had the vote for decades. Federal legislation in 1962 provided all Aboriginal adults with the vote of Commonwealth elections, but with one provision: enrolment and voting were not compulsory. Aboriginal people, unlike other people, were to have the option of whether or not they placed their names on the electoral roll.

The general issue was equality before the law nationwide. And the other constitutional anomaly was the atrocious fact that Aborigines were not counted in the census. To this extent they were not citizens; in keeping with the Constitution drawn up in the era of terra nullius, they had been erased from public life. So the 1967 Referendum became, in many ways, a campaign about saying ‘Yes’ to the full implications of the Aboriginal presence. The 1967 campaign distorted some constitutional realities and technicalities while gathering into itself a whole movement of social thought and feeling.

It’s at this point the authors might have made their book much more interesting than it is. They are very sharp about how the campaign glosses over several issues at once. They give a useful account of how the different organisational strands of the campaign – the Aborigines, the Churches, Labour Movement, Labor Party – converged on the mythical view of the issue. They also point out that some crucial campaigners – such as the tenacious A.P. Elkin, Professor of Anthropology at Sydney – did get the issue into precise focus. All this is pointed enough, but it is sufficiently argued as social history.

The other corrective to the myth about the significance of 1967 is the fact that the federal government had long had the powers to assist Aboriginal affairs, if it so wished. A ‘Yes’ vote in the referendum promoted high hopes that it would do more, and yet the Menzies and then the Holt governments did not, which greatly disillusioned many of Aboriginal campaigners until they took the struggle into Tent Embassies and land rights. And yet, despite the state differences, a national policy was emerging from 1945: it went under the now disgraced term of ‘assimilation’. By not rooting its argument deeply enough in that story this book falls short, and often comes across as an historical quibble.

Yet it is not, finally. It’s a laborious tabling of some of the complexities of an important moment in recent social history. It has seventy-two pages of commentary, and another seventy-odd pages of documents, and is freshly illustrated by photographs and cartoons of the period. It’s a good book for school libraries, and a moderately interesting one for those who want some of the deeper background to what John Howard likes to call the mess of Wik.

Comments powered by CComment