- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

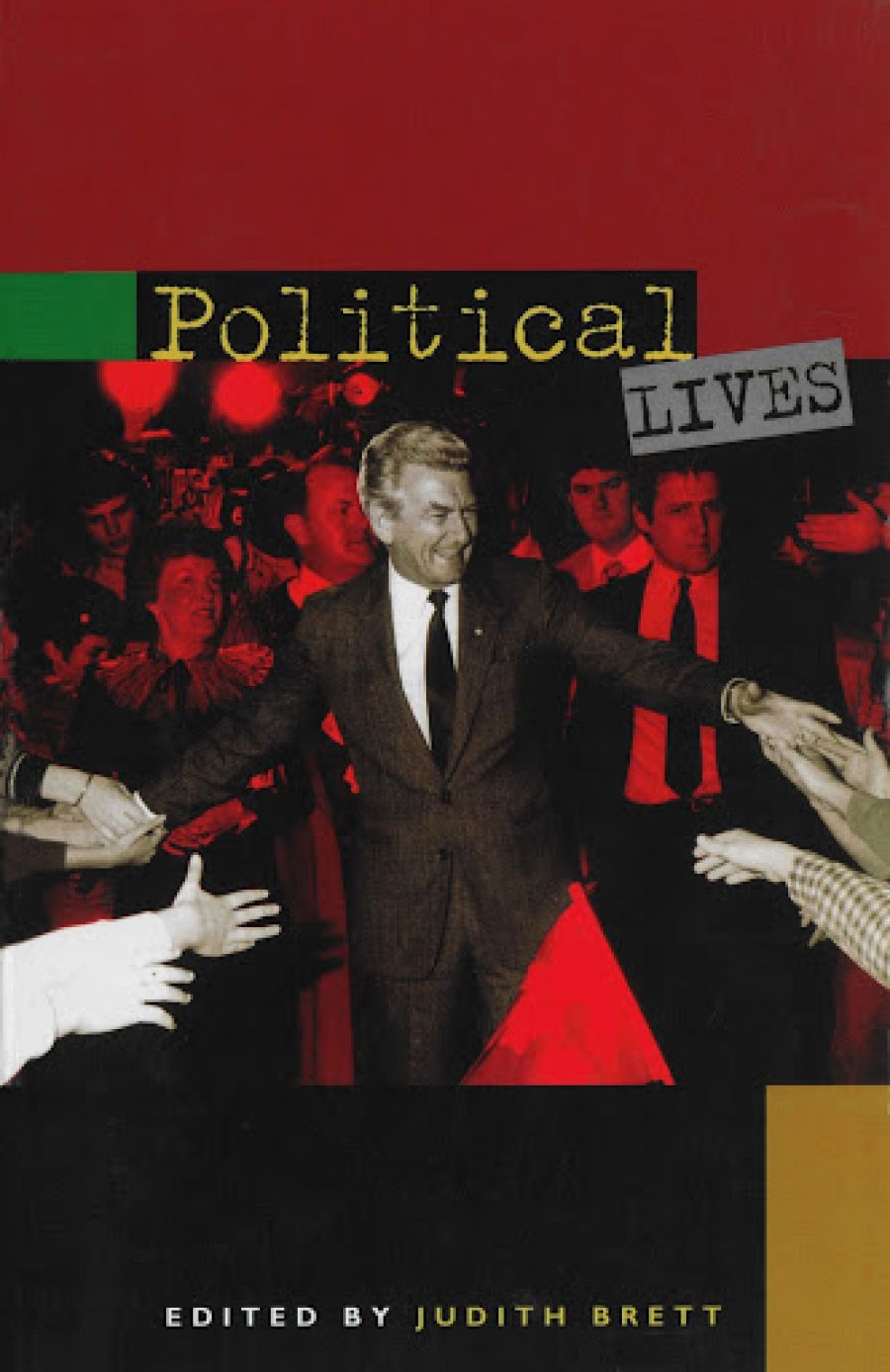

The photo is opposite page eighty. I suspect from the faint fluff in the hair that it’s late 1972. It was taken in the office by a photographer from the Australian News and Information Bureau, a group who were not your art-portrait photographers. The sitting would have been over in a minute; the subject didn’t spend time posing.

- Book 1 Title: Political Lives

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.95 pb, 181 pp

Judith Brett, in her introduction, carries out a pre-emptive strike against the reviewers, necessary in a climate where, she says, ‘to use psychoanalytic ideas in an Australian published book, it seems, is to make one’s book fair game for mockery’. I’m quite happy with psychoanalytical insights making a contribution to biography and for that matter to contemporary political commentary, but they have to hold up. When they bring muddled and pretentious language into the biography, they deserve to be treated with robust scepticism.

Brett, as an exemplar, praises the late Alan Davies, one of the most interesting writers on politics in Australia, whose first book, Private Politics, was highly intelligent and stimulating. But Davies was a meticulous writer and, just as important, modest.

Brett does concede that ‘Common sense, religion and literature are all important sources for the understanding biographers need to bring to their subjects’ emotional lives’ – so far, so reasonable – but then goes on, ‘but they are not systematic, and so do not provide a systematic guide with which to control reflection and intuitive hunches’.

What Brett is claiming here is that psychoanalytic insights provide a kind of grid that can be laid over the map of the subject’s life, which will make everything clear. It is another version of that dreary management consultant psychology which professes to isolate what makes a leader. Using the grid is scientific, not an intuitive hunch. I don’t find the claim credible and this book does nothing to justify it.

There are eight chapters: Brett herself on the Tasks of Political Biography and Menzies’ England; another writer comparing Hawke and Keating, and also on Gough Whitlam, Malcom Fraser, Arthur Calwell, Paul Hasluck, and President Suharto.

The writers are almost totally dependent on journalism and other biographers for the material on which they erect their rickety structures. What is missing is any depth in political background. This is not to demand they have to talk about the details of motions passed etc., but rather that the writers uniformly show no understanding of the reality that political interaction in a lifetime, and even over shorter periods, mould and change personalities, as much as their childhood. The passage of so many politicians from the left to right should be instructive.

James Walters’ rather bad-tempered treatment of Gough Whitlam demonstrates all the limitations of this dependence. Deeply influenced by headline writers, Walters’ views of politics is a very uncomplicated, one-dimensional one. He takes ‘Crash through or Crash’ as though that were the sum total of Whitlam’s politics. In Walters’ vision, Whitlam emerges from his bedroom every morning with his fangs bared, seeking to devour. The reality of the political life of Whitlam is that he didn’t always get his own way and that on many occasions he accepted that. In the ALP patience is just as important as anger. There are times for both. But Walters, fixated on childhood, reduces a complex adult character to a petulant child.

Brett did say that religion was an important source. Of all the leaders, Arthur Calwell was the one most profoundly formed by his religious beliefs, growing up in the rigidly dogmatic Jansenist world of Irish Catholicism, with its sense of being right and that right never changed, an environment that made John Knox look insecure. In 1943 Calwell could no more change his mind on the immorality of conscription than he could abandon the Pope. But Lindsay Rae only mentions Calwell’s being Catholic, as a group discriminated against.

Narcissism is the key word, recurring like a mantra, which on examination boils down to the deep thought that political leaders have high self-esteem, not a blindingly new insight. The trouble with ‘Narcissism’ is that it is like ‘Pyschopath’ in criminology which tells us that a certain kind of criminal is anti-social. Again no great discovery.

Comments powered by CComment