- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia in the imagination of its first European mapmakers was a curious place where odd creatures dwelt. Now that a metropolitan culture emanates from cities to encircle the continent with farms, roads, towns, and nature reserves, the spaces marked ‘exotic’ have shifted. But they’re still here. I know, because I’ve recently moved from Melbourne to Tasmania. Why are you doing this? Asked West Australian colleagues when we talked at a conference in south India. Tasmania’s a great place for a holiday, but how could you live there? It’s so far from everywhere, and you’ll have no one to talk to.

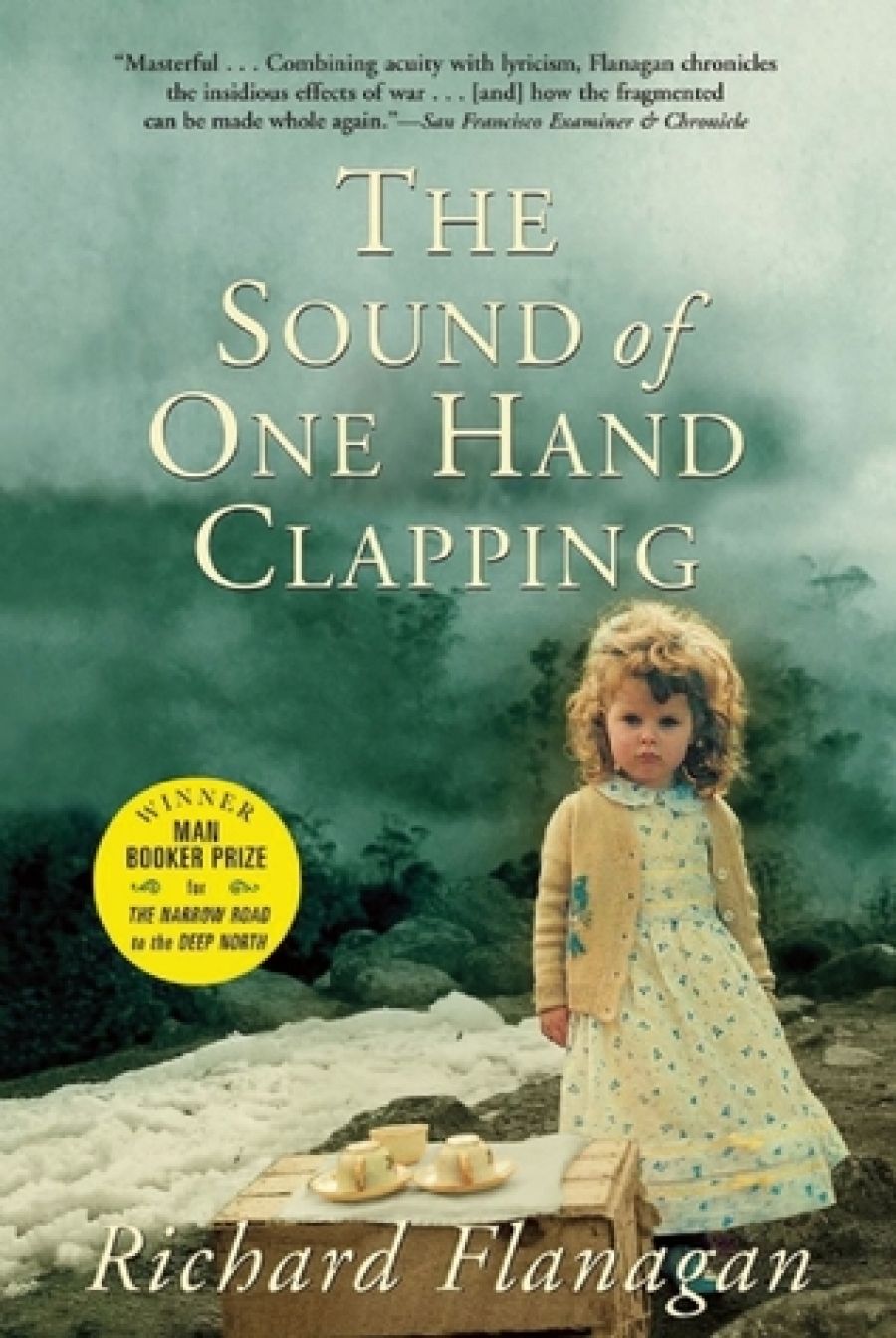

- Book 1 Title: The Sound of One Hand Clapping

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, 425 pp, hb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/qbZRq

Difference, as I know, is a rich soil for story. Think about film and writing in twentieth-century America, and something Southern must soon crop up, either by Southerners or set on their turf. The same may be said now or shortly of Tasmania, and Richard Flanagan will be one of the reasons.

In his second novel, The Sound of One Hand Clapping, Richard Flanagan enters a terrain of story unexplored in fiction with the exception of some fine short stories by James McQueen. This is Tasmanian settlement as experiences by war-scarred Central Europeans set to work in the 1950s on hydro projects which might have made industrial sense in Ruhr Valley but, deep in these cold remote mountains, the dam-building seems to take on a life of its own, the end result a folly unbearable in the human price extracted.

One of the novel’s unforgettable moments tracks Bojan Buloh in 1990 ‘to the place he had vowed never to return’, the dam at Butlers Gorge ‘whose concrete felt entwines with his very flesh’ Bojan had first come there in the early 1950s as a refugee from the mountains of Slovenia where as a child in the alps, he inadvertently crossed into the zone of evil. Climbing a pine tree to hide from an approaching German column led by Slovenian fascists, he sees the ambush of the derelict border house, sees the partisans shot as they flee. All killed except one. Made to dig a hole and climb in. Buried to his neck. Head kicked ‘back and forth like some weird fixed football until the partisan was dead’.

This was a story told by the man who had been that boy waiting in the tree for the cover of dark after the soldiers marched off. No one ever heard from Bojan how for hours he sobbed silently, ‘staring down at that head erupting from the earth at a broken angle, like a snapped flower stem’. What happened to those like Bojan who fled their European homes for an Australian future? asks Richard Flanagan. What happened to people who arrived in the Tasmanian forest with memories saturated in blood?

The Sound of One Hand Clapping is an intensely disturbing book. As a historical critique, it questions the policies which separated refugees from any environment where normality might heal the wounds of war, and kept them confined together in remote isolation as constraining as a prison. On a more general level of social critique, the novel points to ways in which Australia’s commercial and industrial interests have been (and are being?) served by a diaspora of damaged people easily seduced from elsewhere by a desperate desire for freedom.

And yet, in the moral tale played out in the novel there is some hope. It comes through Bojan’s relationship with the other major character, Sonja, his daughter. Sonja was three years old when her mother, wearing a scarlet coat and a dress edged in lace, walked out of the construction camp at Butlers Gorge and disappeared into a snow storm. Flanagan’s telling of Sonja’s childhood offers some of the novel’s best prose. The child, engaged with the unstable world around her, is given a vividness of perception unavailable to her father, closed-off from conversation and endlessly at the bottle (an understandable situation but potentially tedious to the reader who may tire of Bojan’s drunkenness before his loyal daughter does).

Flanagan structures his fiction as a chronological sequence taking place in 1989-90, and constantly intercut with flashbacks. There are elements of the oral storyteller in this, a penchant for circling round events, digressing, moving at oblique angels. Sometimes the narrative moves slowly and threatens to overwhelm the reader with baroque prose; then the pace changes, and the engagement is there again. The novel is haunting, and I shall wait eagerly for next year’s release of the film Flanagan has already directed from a script based on the novel. Another mode of story from the highly talented Tasmanian with an enviable range of skills.

Comments powered by CComment