- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fame and Fathers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I am still puzzling over why Ross Fitzgerald and Ken Spillman chose the odd title, Fathers in Writing, for this anthology of personal essays. Because of its academic resonance, I first assumed that this book would be a scholarly analysis of father figures in literature – or, perhaps, following on from the work of certain feminist theorists, that it would look at how different valorisations of ‘fatherhood’ are embedded in language itself. Then, once I learned that this was an anthology of Australian writing, the title led me to expect a collection of extracts from literature previously published. Or, if these were newly commissioned essays, that they would be pieces in which the difficulties and pleasures of the act of writing itself would take centre stage.

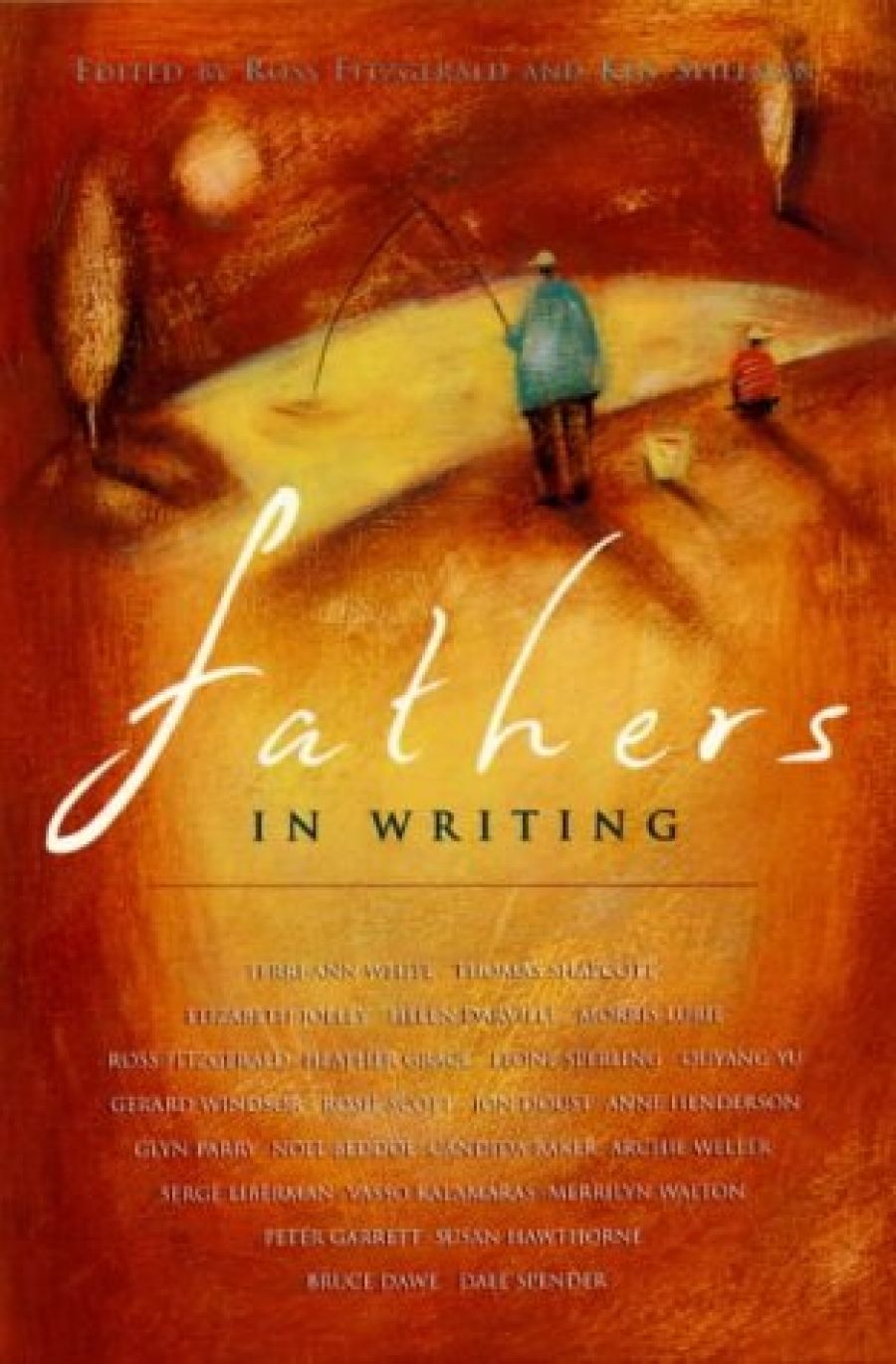

- Book 1 Title: Fathers in Writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Tuart House (UWAP) $29.95pb, 288pp

At first Fitzgerald and Spillman’s introduction seems to promise that the book will address this last expectation – that it is the trickiness of words, the disappearance of fathers behind emotion or cliché, which the authors will confront. The editors tell us, ‘Writers know better than anyone the difficulty of putting things down ... Words make pictures, but often the pictures subvert.’ But this early emphasis on the writing process swiftly shifts to the unique capacity of the Author, as a creature attuned to the vagaries of human nature, to ‘reflect on seminal human relationships’. The editors go on to claim that theirs is an ‘extraordinary gathering of the brave’, from ‘loved literary icons’ to ‘emergent stars’, all engaged in the ‘excruciatingly difficult’ task of writing about family and self.

These seem to me to be very different motives and claims – on the one hand, the work is paramount, no matter who it is written by; on the other, it is the fame and authorial status of the writer which makes each piece inherently interesting. And their lack of resolution tells, I feel, in the patchiness of this collection.

Since the publication of Drusilla Modjeska’s wonderful collection, Sisters, in 1993, family anthologies have become a staple of Australian publishing (off the top of my head, I can think of Beth Yahp’s Family Pictures, the Mother Love series, and Carmel Bird’s Daughters and Fathers). Perhaps it is unfair to dwell on Fitzgerald and Spillman’s introduction here, since the questions it raises ask much about the popularity of this genre as a whole, as well as one’s own motives for enjoying private revelations by public people.

For example, if the main focus of an anthology like Fathers in Writing is the act of writing, should the reader expect the prose to be of a uniformly high standard? And should a greater experimentation with form be expected? (Only Morris Lurie takes the plunge, in ‘Again the Old Bear’, using one-line paragraphs and compulsive repetitions to lyrical effect). If one of the collection’s main selling points is the fame of its writers, are they expected to provide the factual footnotes to, or ‘explain’, their other work? (One can only assume this is the editors’ reason for commissioning Helen Darville’s essay, but, to be fair, she raises that issue herself.) Perhaps this biographical expectation explains the flatness of tone of a number of the contributions. And finally, in such a large collection (288 pages), in which twenty-four writers are featured, if part of the editors’ purpose is to collect together a wide cultural history of fathering experiences, why is Helen Darville the only writer under thirty-five? And is there something troublesome about the assumption that writers will convey such experience best?

Unfortunately, for those of us asked to contribute to such anthologies, their continued publication and the corresponding consolidation of the Australian personal essay into a recognisable genre, have also raised readers’ critical expectations, and made the task of renewing and surprising with the essay harder. For me, Gillian Mears’ ‘The Childhood Gland’ in Sisters, and Brenda Walker’s essay, ‘Over Mountains and Black Water’ in Bird’s anthology, have set the enviable benchmark for essays about family – for the graininess and tenderness of their detail, the iconic nature of clearly observed actions, the lucidity and calmness of the thinking voice.

There are some of these moments which catch at the heart or mind in Fathers in Writing. Serge Lieberman’s description of his mother, standing by his father’s body talking to her son, the doctor, who is in this instance helpless – ‘Sergie, he’s still warm! Sergie, you saved him before! Try, try to do it again!’; Elizabeth Jolley’s description of her father’s delight in a new fridge with its ‘lake of quiet milk, blue as dusk’; and Ouyang Yu’s descriptions of his father’s application of the ‘tonic method’ of poetry (turning ‘trash into treasure by adding only one or two more simple details’) to his own life.

Yet, in this thick book, these moments do not come frequently enough. Too often, one father’s experience is taken to stand in for fatherhood as a whole, and to ‘naturally’ include the whole shop of marriage and domesticity. (Thomas Shapcott’s jibes at those who would dispute these ‘givens’ – ‘believe me, feminists’ – are not endearing.) Other essays, although the writing is engaging in bursts, are mired in the recitation of bald, biographical fact.

The essays I enjoyed most were those which stretched the concept of fatherhood out most broadly. Terri-ann White describes the early death of two gay male friends from AIDS and the fathering role taken by gay carers, placing their stories against the expectations of continuity and descent which circulate between fathers and sons, and from these instances of fracture in the ‘natural order’ asks productively, ‘What it is that appeals to men, anyway, for them to participate in the making of a child?’ I wished this essay was longer. Ouyang Yu undertakes a similar project to Paul Auster’s in The Invention of Solitude, trying to find a way to understand the secret life of an absent father. In his father, who taught himself different languages solely for the lonely pleasure of reading, Yu traces the absence of fathers in the Chinese language. Glyn Parry’s tender essay ranges from his father’s house in the Perth hills to his childhood in Wales, to his cough, possibly the result of his presence as a guinea pig at British nuclear tests in the Pacific, a cough which makes Parry ‘want to tear a pair of X-ray specs off an old Richie Rich comic for a quick diagnosis’. These thoughts lead back to the powerful parental role of nations, and cultures, and Parry’s own desire for an Australian republic.

Fathers in Writing promises much, but suffers from a lack of direction and form. I suspect, as the family anthology continues to evolve, editors will need to give the writers they invite to contribute a tighter brief.

Comments powered by CComment