- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Called to the bar

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

No icon better encapsulates the ethos of male culture than the pub. Sharing a beer in this bastion of male conviviality has been a defining experience in shaping Australian male identity. The pub as a cultural and social institution has attracted the attention of many historians, but none have considered the ubiquitous and yet mysteriously anonymous figure of the barmaid. Although represented in fiction and film, and up until recently, a part of the very fabric of pub culture, the barmaid remains an elusive figure in Australian history.

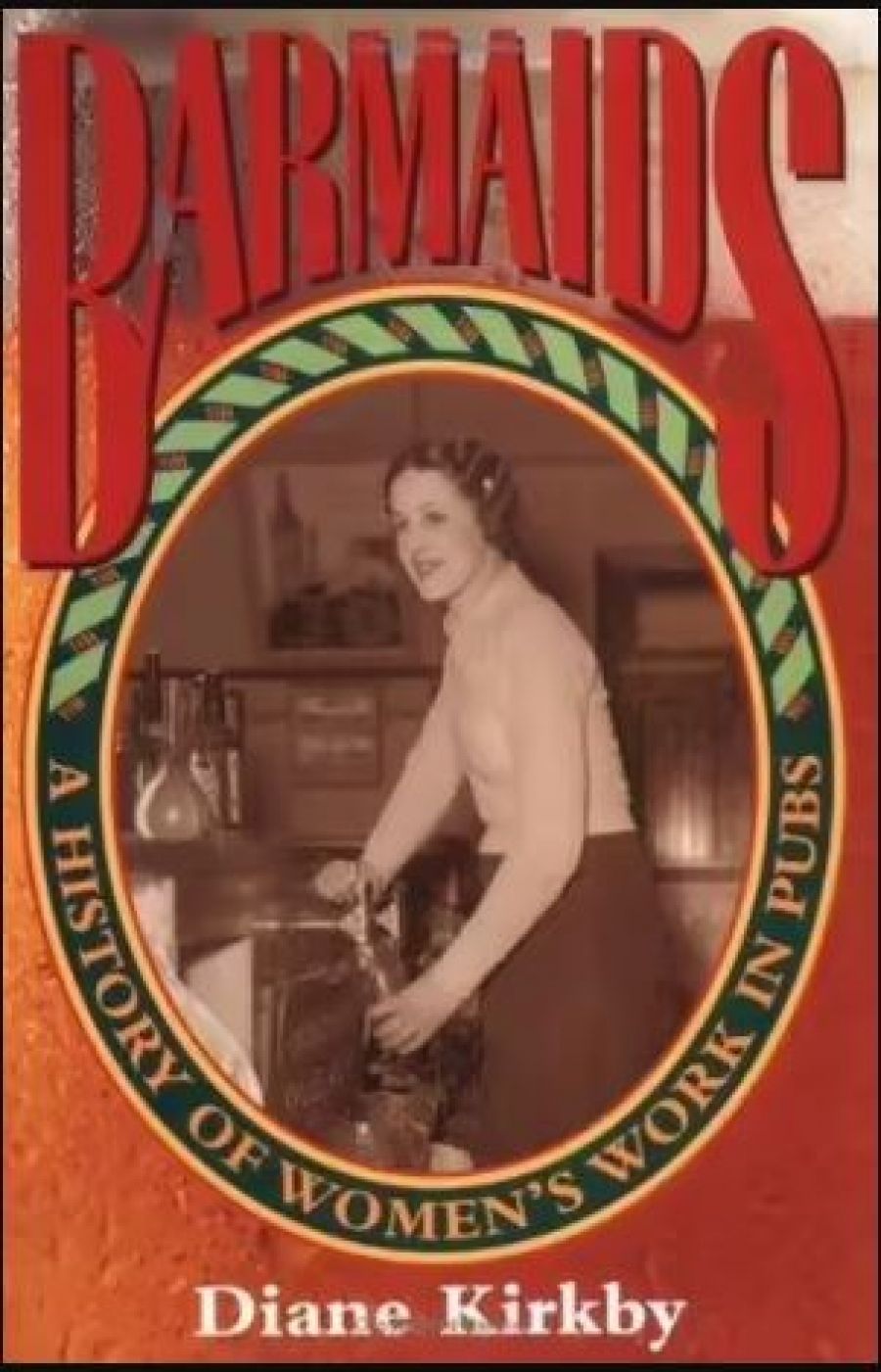

- Book 1 Title: Barmaids

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of women’s work in pubs

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press $90 hb, $29.95 pb, 256 pp

The ‘barmaid’ as we know her today arrived in significant numbers to Australia during the gold rushes. From this period and towards the end of the nineteenth century, the industry attracted women because the conditions were better than those of domestic service, although the jobs shared tasks in common. The sexual connotations of barwork developed as the job evolved. Working in the full view and scrutiny of the male gaze made barmaids sexually vulnerable and associations between the barmaid and prostitution are as old as the professions themselves. But such perceptions set a discourse which devalued the skill involved in barwork.

Through these various threads, this book deftly weaves the history of the barmaid within the wider context of women and paid work, the sexual division of labour, changes in the hotel industry, and legislative reforms which attempted to regulate hours and conditions of barwork.

One of the most compelling aspects of this book is the way in which it captures the ambiguous attitude of so many organisations towards the barmaid. Barmaids were to endure the slur and smear of their character in their workplace. The strongest opposition to women in bars came from temperance groups, who saw barmaids as simply seducing men. Early feminists were more ambivalent about how to view them. They considered their work ‘unworthy’, but they supported women having a right to earn a living. Barmaids were perceived as having an unsavoury character, complicit in man’s addiction to the demon drink. She at once became the male symbol of women’s desires and women’s symbol of economic independence. Unions like the Liquor Trades Union were also less forthcoming in their support as they were concerned to protect the interests of male workers.

In these narratives, a dynamic sense of change over time is captured with economy and subtlety. While the Depression made barmaids vulnerable, there were shortages during the war. The six o’clock swill changed the drinking culture of men who frequented pubs: no longer were they the leisurely drinking houses, but hot houses of pressured drinking. With the introduction of licensed clubs and with women frequenting these clubs, hotels had to compete with them. In the late twentieth century, a greater variety of pubs emerged with a more professionalised image.

Another impressive achievement of this book is the way it brings coherence to a fragmentary history. The gaps in Barmaids come from the paucity of sources on the subject. The testimonies of different classes of barmaids would have shown how they perceived themselves, and thrown into relief the variety of experiences they endured as workers and as women. The specifics of barwork, and how this shifted over time, could have also fleshed out this picture more fully. While the racial element is touched on in relation to Aboriginal and white relations, the impact of post-war migration, so significant in shaping eating and drinking habits in post-war Australia, is another important dimension to this history. The pubs and the barmaids who served and sustained marginalised groups, like gays, blacks, and immigrants could have offered a counterpoint to the traditional working class pub and its cultural matrix.

This is an exemplary and exciting study of work and leisure and of how the workplace is a site where meanings of gender, sexuality, and notions of citizenship are defined, shaped, and reshaped. Kirkby’s interrogation of the fascinating and rare photographs provides an important and illuminating narrative to compliment the written text. The changing nature of the status of the barmaid is beautifully encapsulated and is foregrounded against the backdrop of a society and industry which are constantly in flux. In the past, barwork was an extension of the domestic labour women have performed to serve men. Barmaids persuasively reminds us that although this work has been paid work, it has been undervalued and sexualised and in this respect, shares much in common with other work women continue to perform behind and beyond the counter.

Comments powered by CComment