- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Society

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Family is surely the house of all feeling. Yet when we are in our early twenties, if not before, part of our dream of being grown up is to imagine the day when we will leave this house. Years later, many of us realise that we never did, that the building may be prison or comfort, but it is also us. How one adapts to this sage correction by time and maturity largely determines the emotional comfort of middle life and beyond.

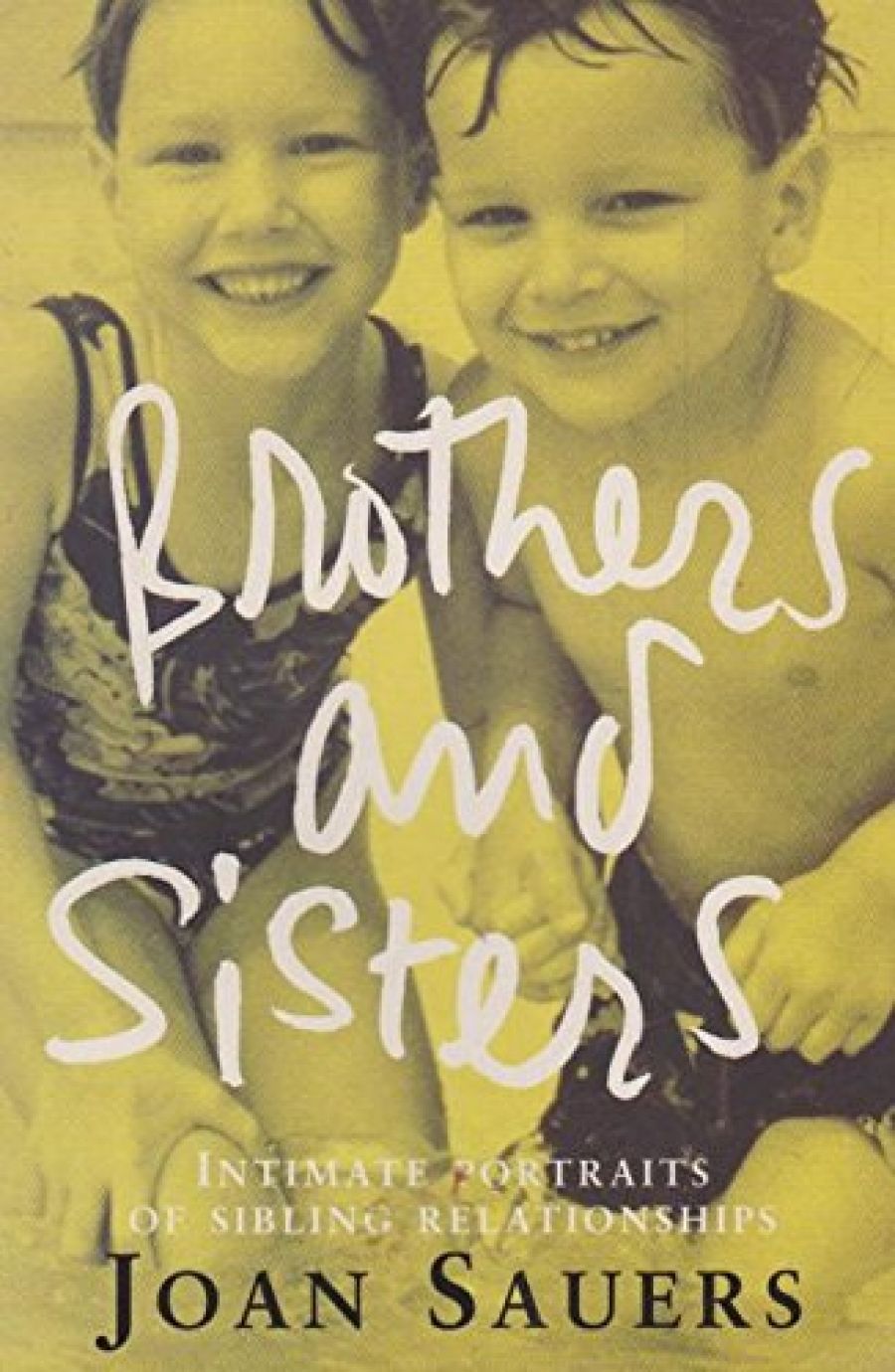

- Book 1 Title: Brothers and Sisters

- Book 1 Subtitle: Intimate portraits of sibling relationships

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann/Random House, $19.95 pb, 343 pp

In her ‘intimate portraits of sibling relationships’, Joan Sauers strikes me as one who has an ambiguous relationship with this knowledge, which is no impediment, and probably an assistance, in the compilation of such a project. Sauers, however, began with a different rationale, one she struck upon, or was struck by, after reading about the ‘Darwinian’ theory of family relationships in Frank Sulloway’s Born to Rebel. Sulloway’s theory, now fairly well known, holds that we are the product of both the conflict between a drive to support the survival of family and sibling/s and a competing drive to assert ourselves as being of primary importance. The primitive, often aggressive instincts, required for the latter, and how we resolve them with the more altruistic elements of the former, is what gives each child’s personality its idiosyncratic ‘tilt’.

There is a strong profile of personalities in Brothers and Sisters; many come from creative backgrounds, with parents in theatre or writing and therefore known to the reader. One could be picky and say that, in terms of the theory outlined in the introduction, this selection is a trifle slanted yet a certain amount of voyeurism must be allowable in such a book. There are charming glimpses of the Bell sisters, Hilary and Lucy (daughters of John Bell and Anna Volska of the Bell Shakespeare company fame) and the refreshingly natural Brown sisters, Rosie and Matilda (daughters of Rachel Ward and Bryan Brown).

Given the professions and personalities in the book, however, the possibility of artful subterfuge hovers at the edge of quite a few interviews. Hilary and Lucy Bell, who could most exploit this (Lucy is an actor and Hilary a dramatist) do not and succeed in convincing us that (as well as being as beautiful and talented as their parents) they have withstood the pressures of creative jealousy. That kind of tension, on the other hand, overwhelms the interview with twins Phil and Grant McAloon (TV script writers for Heartbreak High and GP respectively) and neither one is prepared to get off the stage.

Predictable and a little repetitive at times, this collection still offers some surprises: the Greek brother and sister, John and Taula, express a disarming resentment at childhood outings with the ‘relos’ rather than with their own parents; the big families seems stereotypically jolly until we come to the Morans, who fought a legal battle over ownership of the family farm so bitter that one brother is alienated from the others; the ‘ideal’ adopted multicultural family implodes as the teenage children must become parents to each other when their own adoptive parents divorce and re-partner.

Through many of these families runs the continuous thread of artistic and musical talent but I would want to add that, whether this is so or not, it is humour that knits siblings and family members together – and a satirical humour at that. Just about every interview in this book proves how certainty, and the arrogance it brings, is the enemy of family cohesion, and how humour prevents the condition developing. Only humour could achieve this healthy balance between feeling both fundamentally important and cosmically irrelevant, at the same time. Nowhere is this more compellingly obvious than in the relationship between Gertie and Judy, sisters who survived Auschwitz, where the second half of that message was their daily reality for years.

To the very personal portraits that emerge in Brothers and Sisters, as well as the Darwinian theory of family and sibling survival to which it is loosely annexed, should be added the other issues that naturally arise. These include the number of siblings in a family, birth order, parental methods, creative talents and backgrounds, childhood illnesses, deaths and historic happenings. This, I would argue, is nearer the total picture of the genealogy of personality. It is not quite as neat a theory perhaps as Sulloway’s, but it is nearer to life. The computation of all of these factors, alongside the acknowledged primitive sibling dynamics, is, of course, an impossible form of emotional mathematics and would doubtless prove a dreary project. Brothers and Sisters we have, in any case, all the important equations on display. I suspect that there is no exact or easy answer to why certain sibling alliances, or antipathies form; or why some are fixed for life while others, blissfully, evaporate.

Comments powered by CComment