- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Both Dennis Haskell and Andrew Sant are primarily domestic poets. Family and friends comprise the milieu of many of their poems, which attempt to transform quotidiana into something of enduring interest. The chief danger of this type of poetry is that the prevalence of so many poems about family members and friends results in a poetic environment that can resemble a vast, monotonous suburb. If most domestic poets seem indistinguishable from each other in their subject matter alone, then the situation of contemporary poetry becomes further muddled when this homogeneity is bolstered by a general complacency with language.

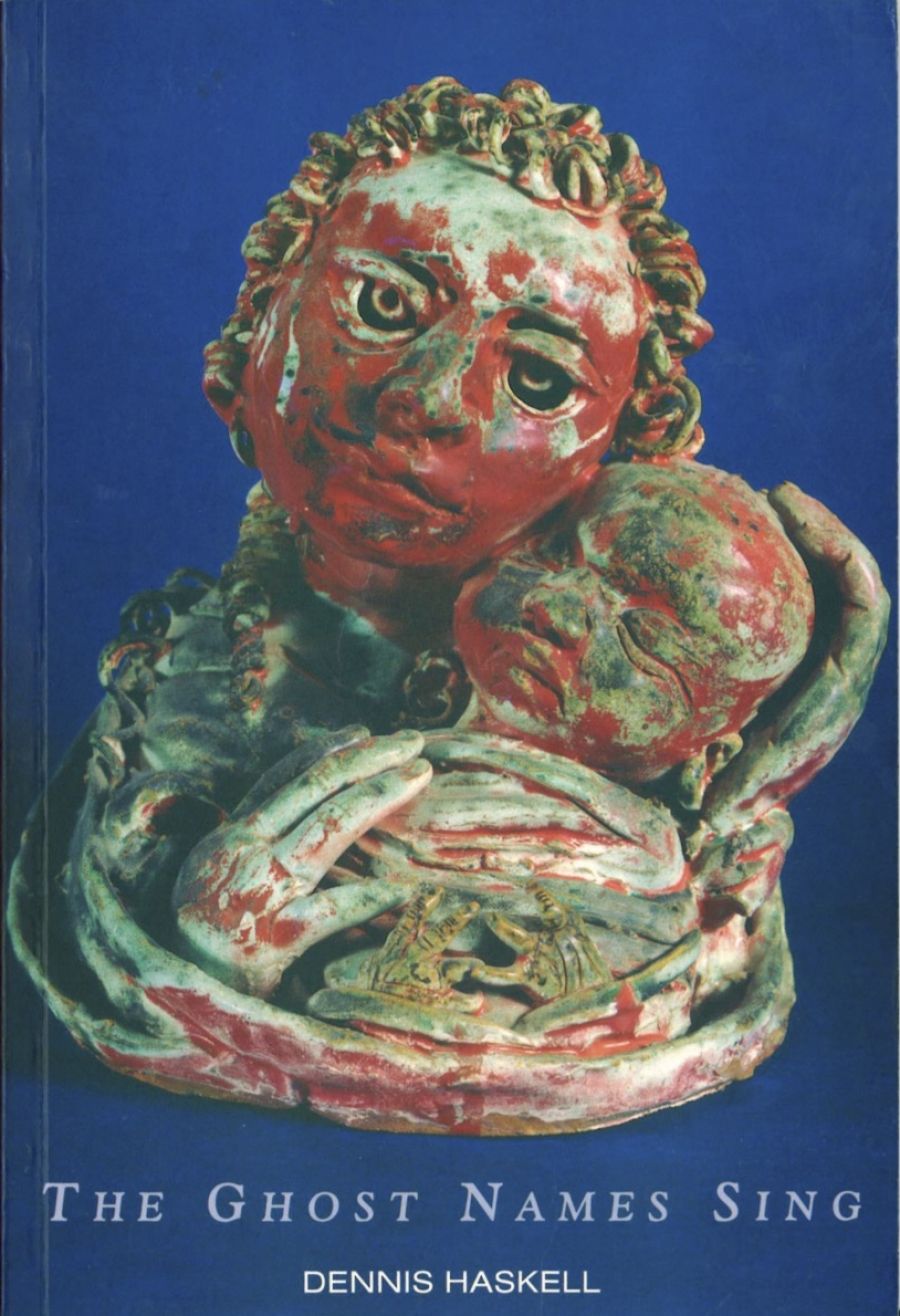

- Book 1 Title: The Ghost Names Sing

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP $16.95 pb, 78pp

- Book 2 Title: Album of Domestic Exiles

- Book 2 Biblio: Black Pepper $15.95 pb, 71pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Apr_2021/Andrew Sant.jpg

Dennis Haskell’s poetry, in particular, suffers from inadequate attention to the possibilities of language. Each of his books offers a staple of domestic poems – with the love poem and elegy prominent – as well as social and religious commentary, often presented as satire/parody or tourist/travel poems. Unfortunately, none of the poems in Haskell’s third volume, The Ghost Names Sing, are as strong as the best poems in his previous collection, Abracadabra (1993), which are marked by emotional restraint, subtlety of diction and detail, and a searching intelligence.

Although Haskell has been praised for his craft, his lines seem more flaccid and prolix than a careful poet’s lines should. His gestures toward rhyme tend to limit themselves to rhyming the last word of the poem with a word one line, or a few lines, before it. Such a technique has the potential of making the language sing but can also weaken an already mediocre poem: ‘the mind understandably squirms:/after us there’s worms’. Haskell’s heedless use of cliches further betrays his supposed adeptness at the craft of poetry: ‘the heat thickens’, ‘The conversation thins’, ‘the dates creep up on me one by one’, ‘I’ve ached to think back/to when I first glimpsed you’, ‘she … carried an air of defiant silence’. Such unarduous writing in a poet’s third collection is disconcerting.

However, The Ghost Names Sing does include some modest successes – ‘Unsuccessful Interview’, ‘On Thinking about the Probable Re-election of Richard Court’, ‘Evening Flight’, and ‘The Second Going’, which demonstrates Haskell’s gift for satiric parody and ends with real flare: ‘And what bankrupt millionaire, his turn come at last/Slouches towards the Terrace to be scorned?’ (though ‘The Baked Style of Unemployment’, a parody of ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’, seems redundant). Because a poet’s effort to affirm the importance of the mundane requires an extraordinary sensibility driving it, these poems are mostly just ordinary. Where love poems, elegies, family poems, and social commentaries can locate the momentous – and even the glorious-in the everyday, Haskell’s casually familiar’ poetry ultimately falls short of the potential of his subject matter.

Andrew Sant, on the other hand, writes intellectually and linguistically compelling poems that deftly wed structure to subject matter. The poems in his fifth collection, Album of Domestic Exiles, offer a skilfully ‘controlled abundance’ and invite and sustain repeated readings. As the book’s title suggests, Sant is interested in the psychological and emotional effects of various types of exile, as in the work of Elizabeth Bishop, whose poetry Sant ‘s more than superficially resembles. The book’s title sequence consists of eight short poems

focusing on objects exiled from domestic use – LPs, candles, black-and-white snapshots, Mussolini’s umbrella. Sant considers the poignancy of feeling perpetually unsettled rather than the pathos of it (political exile is absent in this collection, which, after all, is an ‘album of domestic exiles’). This angle brings the poems closer to individual experience while avoiding sentimentality, convenient expressions of emotion, and hackneyed language, so that Sant surfaces with personal poems of universal import.

In his examinations of exile, Sant illuminates the experience of displacement in numerous poems – ‘Haute Locale’, his mock ode to the United States, that ‘generous ally, home of the free/cliche’; ‘Elegy for the Queen’s Head’ (‘Let’s face it, since she’s licked, / … The rest’s expressly philatelic.’); and the more serious ‘Voyage’, a dramatic monologue about ‘Britain’s child migration scheme’, a euphemism for the export of unwanted children. Although Sant is serious about exile, he is devoted above all to his art: when ‘everything is leaving’, ‘Language, I find, is home.’

This preoccupation with language is manifest throughout the collection. Sant’s well-turned lines advance an often-complex syntax that enhances the rhythms of his poetry. ‘Tactic’, a thirty-six-line poem consisting of two sentences, never strains under the syntactical manoeuvres that keep the poem moving; and ‘Profit and Loss’ is admirably textured yet lyrical:

the accounts are windswept;

where memos flew, gulls blessed with subatomic guile encounter walls that are not there, swoop through

and up beyond the roof, a perch of air; the absentminded managers, sportsmen all, have blown their cover

… and can’t be seen though it’s still early afternoon,

Sant’s best poems demonstrate Bishop’s low-key yet scrupulous style; and like Bishop, Sant seems equally comfortable in traditional forms and in a contemporary verse libéré (freed verse), as opposed to the prose hacked into lines that many poets call free verse. Sant’s rich verbal layers and cadences are almost always compelling, and many of these poems reveal the ‘whorls and rips’ made possible when an exceptional facility with language collides with everyday subjects.

Comments powered by CComment