- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cricket

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gideon Haigh is turning into something of a one-man industry on cricket in Australia. Following highly successful books on the Packer revolution, Allan Border’s reign, and a recent defence of the Ashes, he has now turned his attention to the crucial years 1949 to 1971 when Australia went from being undisputed world champions to a side being overtaken, not merely by England but for the first time by South Africa, which would shortly be expelled because of its practice of apartheid, with the so-called Third World countries showing that they would not remain beaten for much longer. It opens, in other words, with Donald Bradman about to depart and ends with the ruthless sacking of Bill Lawry and the arrival of Ian Chappell as new captain.

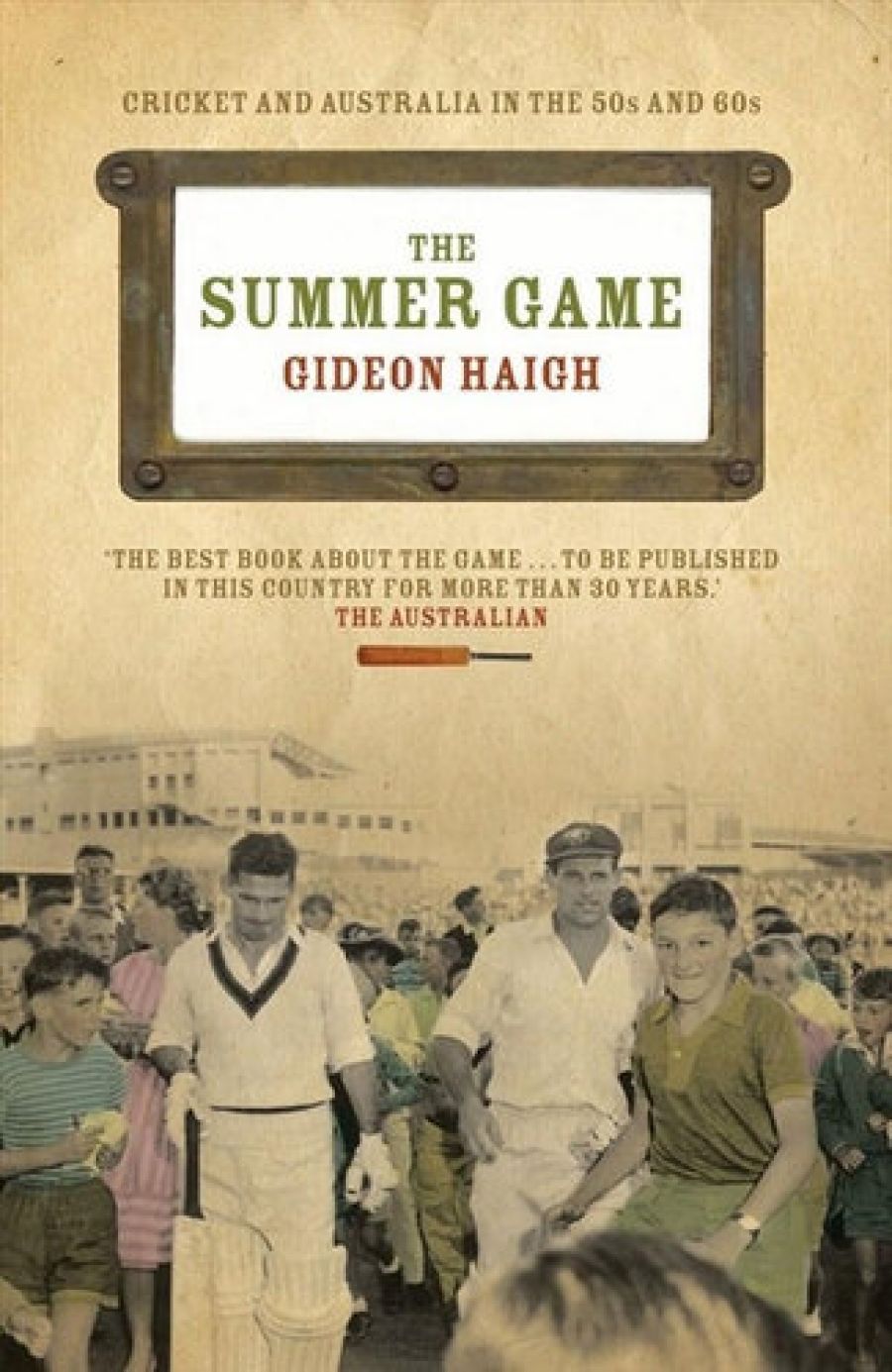

- Book 1 Title: The Summer Game

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australian Test Cricket 1949–1971

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing $39.95hb, 356pp,

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/AqoYN

That makes it a kind of prequel to the story of World Series Cricket and the temporary eclipse of Australia as a cricketing power during those years. The book clearly foreshadows this. Haigh’s interest is, as always, in the culture of the sport as well as mere results and he intercuts accounts of individual tours with commentaries on what it was like to tour in the 1950s and the vagaries of cricket administration. As he says, his interest is ‘people and period rather than games and scores’ although there is a very useful list of the results of every Test played during the period.

If there is one recurring theme in this book it is the constant incompetence and tactlessness of the sport’s administrators. It is not a new concern; it goes back as far as 1912 and the controversy over whether the Australian Cricket Board or the players themselves should choose the manager for the England tour, culminating in six of Australia’s finest cricketers including the captain Clem Hill refusing to go on the tour. But even allowing for a different atmosphere and assumptions about authority in the 1950s and 1960s, this account of the behaviour of the administrators makes astonishing reading.

It opens with the inexplicable omission of Keith Miller from the team to tour South Africa in 1949 (he was afterwards included as a replacement when Bill Johnston and Ray Lindwall suffered injuries) and closes with the Board’s request to the players that they play another Test in South Africa in 1970 – in return for which they offered them the princely sum of an additional $200. Ian Chappell led what eventually became a united revolt against the Board, which paved the way for the advent of World Series cricket seven years later. The period under consideration was marked by a steady decline in the real wages of players. In 1952–53 they were paid seventy pounds per home Test match, five times weekly earnings. Between 1954–1955 and 1968–1969, average weekly wages more than doubled, but the base Test fee increased just nineteen per cent.

Players could not write on any match in which they were participating, and wives were not allowed on tour. Where nowadays it’s extremely difficult to get players like Border and Mark Taylor to retire, the opposite was true in this period and the list of talent prematurely lost to the country’s Test side is a considerable one: in the 1950s, Saggers, Moroney, Ridings, Haddrick, and Ian McDonald and George Thoms, both of whom pursued medical careers. Others went to England to play cricket professionally and some stayed there. Twenty years later, players like McKenzie and Allan Connolly were still exhausting themselves cricketing all year round and making far more money playing for English counties than Australian Tests but with the inevitable result that their careers ended prematurely. Haigh points out that between 1964 and 1967 an entire Australian XI was lost to the game when it still had good cricket left in it: Burge, O’Neill, Thomas, Craig, Mclachlan, Sincock, Veivers, Philpott, Hoare, Gaunt, Shepherd, Potter and Bob Simpson. The oldest of these players was thirty-one. The gifted Bob Cowper had retired at twenty-seven.

Haigh is sympathetic to the players’ cause, but he is sometimes benignly conservative, describing 1950s Australia as feeling like

the happiest, healthiest, sunniest and most fortunate country on earth. It was a land of negligible foreign debt, one percent unemployment, spiralling wool prices and booming factory output, a land with the world’s shortest week and five per cent annual GDP growth.

He doesn’t, however, mention – there, at least – the White Australia policy, the attempts to outlaw communism, the Stolen Generation, or the fact that the employment was almost entirely for males. He notes our role in the Korean war with seeming approval. To be fair, though, he does concede later, in discussing the West Indies, the fact that

Australians might have barely acknowledged their own black population, denied them the vote and broken up their families, but they saw nothing incongruous about applauding a coloured cricket team.

Haigh’s hero is Sir Robert Menzies, who plays a prominent part throughout most of the period, personally intervening to provide financial assistance, ensure that a passport arrived on time or beer was available at embassies on sub-continent tours. Haigh observes,

It has always surprised me that those who purport to analyse Australia’s longest serving prime minister are so incurious about his fascination for cricket: devotions and hobbies are so often an index of personality.

I had always assumed it was merely one more example of his love of all things English. In my Labor-voting household, I was brought up to believe, in fact, that Menzies developed his passion for cricket quite late in life, retrospectively as it were, but this account would suggest that this was an unfair shibboleth.

Despite his dismissal of ‘games and scores’, Haigh does in fact offer a crisply written account of on-field activities as well as off, spiced with highly entertaining anecdotes and quotes from the players themselves. He interviewed dozens of the participants and there is an extensive bibliography at the back of the book. There are no footnotes, however, and I would have liked to have known the authority for some of the quoted statements. All in all, though, the book is great reading and great value for any cricket lover.

Comments powered by CComment