- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seriously Shallow

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Popular fiction is often character-driven. An immediate distinction between these heavily-populated novels would be that if I met the main protagonist of Scott’s book I’d want to have coffee with him whereas if I met Aitken’s I’d want to slap him.

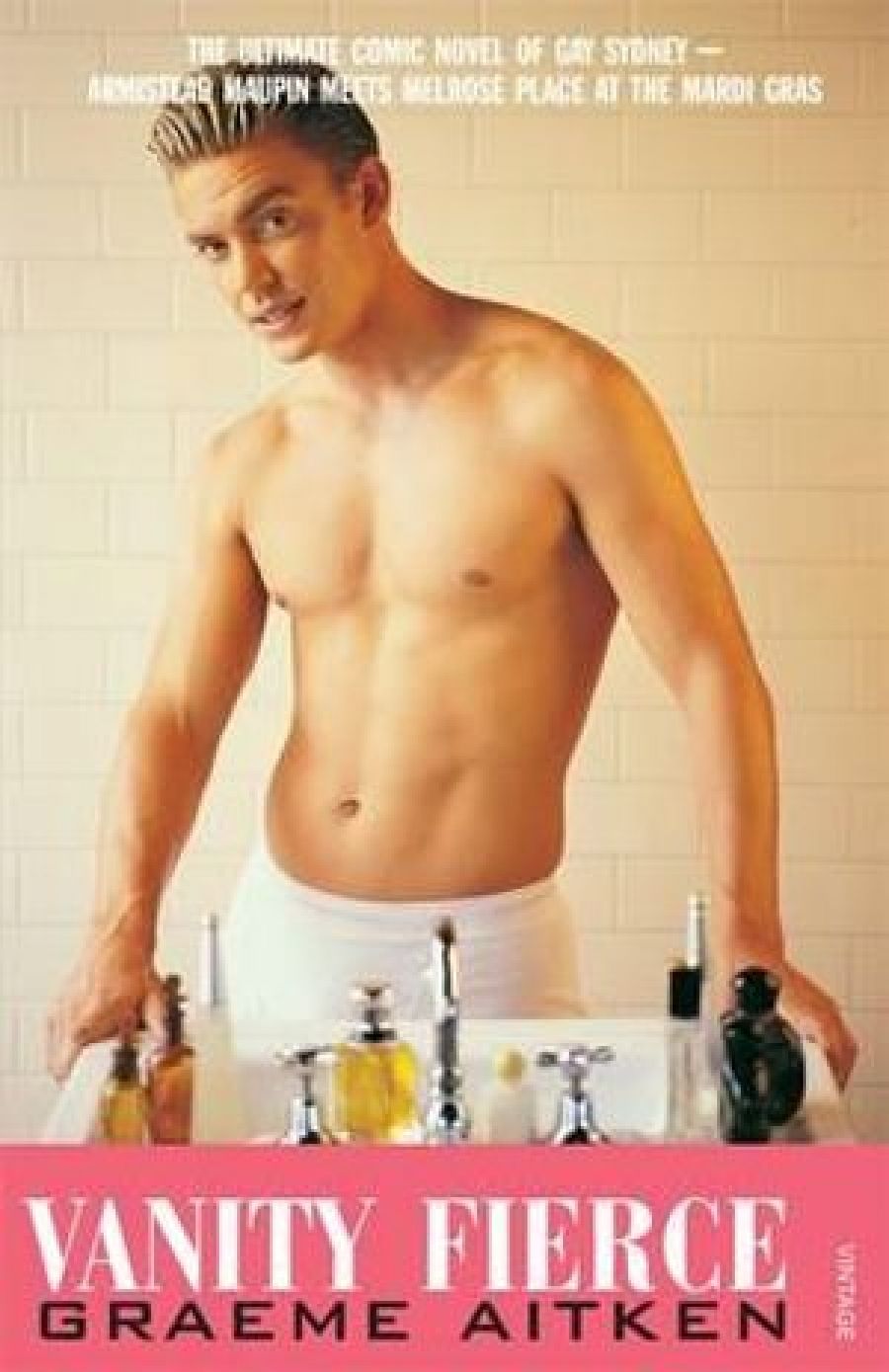

- Book 1 Title: Vanity Fierce

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage $16.95 pb, 518 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/vanity-fierce-graeme-aitken/book/9780091837167.html

- Book 2 Title: Gay Resort Murder Shock

- Book 2 Biblio: Penguin $16.95 pb, 344 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2021/Archives_and_Online_Exclusives/gay resort murder shock.jpg

Vanity Fierce is, among other soggily undigested genres, a gay Tom Jones, combining the coming-of-age, coming-out, coming-to-terms, and coming-in-anything-that-moves modes, both picaresque and episodic, with the rhythms of soap opera and soft porn-romance. Stephen, the golden boy narrator, expends fifty-six pages telling us how fabulous and irresistible he is before moving in to William Street, Sydney and the gay subculture. By page eighty-one, Anthony (Ant) has become his quarry. By page ninety-six, he’s sworn to save his anal deflowering for Ant. By page one hundred and seventeen, he’s grilling Ant’s ex. By page one hundred and sixty, he’s begun plotting against Ant’s new boyfriend, Carson. By page one hundred and eightysix, he’s seduced then rejected Carson because he’s paranoid about HIV infection. By page two hundred and twelve, Carson and Ant are buying an apartment. By page two hundred and twenty two (startlingly titled ‘Part Two’), I couldn’t care less.

The challenge, as Austen and the creators of My Best Friend’s Wedding well know, is to create a likably-misguided interfering schemer who is taught by others, and by comic complications, to be themselves and grow up. And, as sitcom and romance writers know, it can be exquisitely suspenseful to have a besotted protagonist playing just-good-friend to their love/lust-object while plotting eventual conquest. The inert bulk of Aitken’s novel, however, alienates readers by constricting them so tightly to Stephen’s point-of-view, and in four hundred pages, he’s barely learnt even to second-guess Ant’s emotions.

Depending on your patience, there are big-canvas compensations. There’s an engaging cavalcade of dramatis personae and stock scenes: Strauss the wisely-sardonic old queen, Blair the obligatory fag-hag, lubricious losses of virginity, the odd romantic moment, some comic set-ups, a moveable junkfoodfeast of sexual partners who never live up to Stephen’s expectations, a roster of fellow narcissists obsessed with age, body hair, physique, skin tone, fashion, and an aerobic regimen of sexual exercise. There are moments when the narrative opens out on self-knowledge, or into inklings of empathy, that almost make the long repetitive corridors of banal self-psychologising and self-delusion worthwhile.

His handling of characters living with HIV/AIDS is informed without being safe-sex-brochure-y, emotionally raw without becoming mawkish and very nearly successful in its Bildungsroman progression towards maturity and understanding. It is, all in all, far too effective for the intercalated narcissistic satire to be experienced as anything other than diffracting and distracting, artificial bathetic light relief like excerpts from the new Peter Allen musical. This problem becomes literal in the book-within-the-book, Carson’s memoirs, regularly disparaged by our narrator. While this allows us to temporarily escape Stephen, it is an unhappy device, since Carson’s writing skills are no worse than Stephen’s, and as with most sections of Vanity Fierce, it is badly in need of surgical editing for length, pace, stylistic tics, and exaggeration. Worse, it’s when Aitken attempts a semi-serious critique or commentary on the enclosed world his characters protectively excrete that the tofu tedium of his prose becomes clumsy rather than merely uninspired.

Scott ditches pretense at ethnographic satire and does better, slicker, funnier and faster what Aitken can only manage intermittently and incoherently. Gay Resort Murder Shock centres round Marc, an unwillingly ageing accidental opera-queen detective, more Hettie Wainthrop than Inspector Morse. He escapes the roar of inner Sydney flightpath life only to stumble upon a conspiracy (or three) involving a homophobic fundamentalist Christian group (led, naturally, by a gorgeous pastor), a newly-developed Queensland gay island resort, a posse of American A-list gay tourists, a decapitated drag queen, underdressed hospitality staff, gruesome murder, a pushy dyke journalist, a conniving ex-rent-boy, and you get the idea. A freebie holiday as a Community Liaison stand-in becomes a sitcom-gone-wrong as Marc and Paul (his self-obsessed sidekick with the well-stuffed quiver of one-liners) try to track down the culprits with little finesse and fewer leads. It’s a romp with neat cul-de-sacs for set-pieces (the café culture, the fag-baiting closetfag, the double-bind of escalating alibis, the red herring, the suspenseful botched search for clues) but most are effectively and seamlessly integrated. While the nuts’n’bolts of plot mechanics and cross-wired backstories so vital to the detective mode are less surreal and sure than in the prequel, One Dead Diva, it remains an enjoyable read.

Both novels, however, have a major structural flaw, the climax and denouement are neither so funny nor risky nor satisfying, coming neither as shock nor fusion nor detonation, and both are cover-blurbed as fitting within the Armistead Maupin Tales of the City mould. Neither lives up to the comparison.

Oscar Wilde once said (and often proved) that ‘Seriousness is the only refuge of the shallow’. These very different gay (no, Virginia, ‘queer’ is different again) novels offer you a choice between the shallowly serious and seriously shallow.

Comments powered by CComment