- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Veronica Brady is a highly respected critic with long and distinguished experience in the academic and literary worlds. She understands as well as anyone, I am sure, the mysterious workings of the imagination – how a feeling, an image or an impression may strike a spark capable of igniting a flame that fuses often contradictory thoughts and experiences into the ‘little room’ of a memorable poem. So it must have been a deliberate, though to my mind regrettable, decision that made her concentrate on Judith Wright’s life as a conservationist and campaigner for Aboriginal land rights almost to the exclusion of everything else – poetry included – in this ample and painstaking biography.

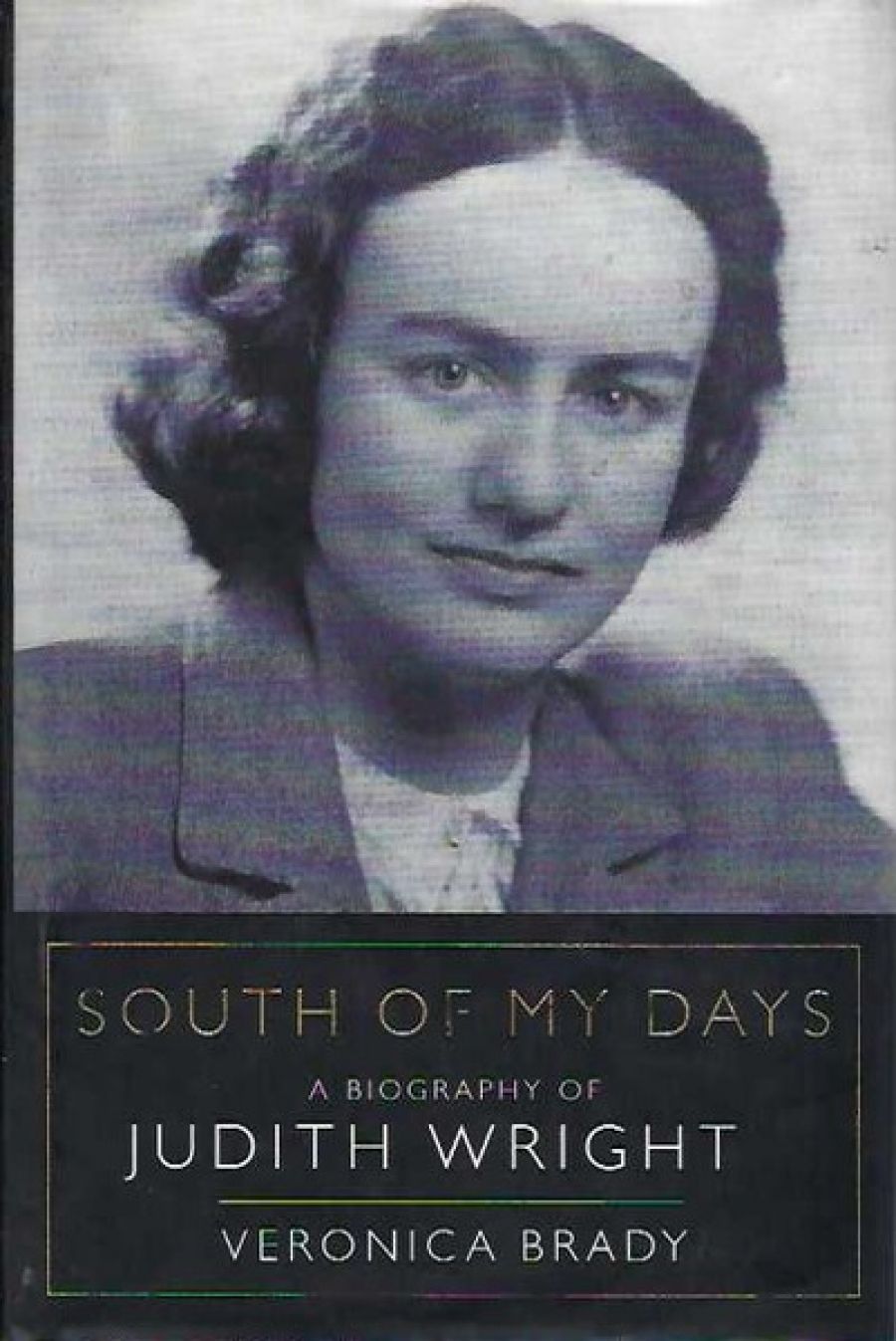

- Book 1 Title: South of My Days

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Biography of Judith Wright

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, $45 hb, 586 pp

Admittedly, Brady quotes generous slabs of Wright’s poetry – 1,500 lines or so according to my rough computation – as well as extracts from her prose works, chiefly The Generations of Men and The Cry for the Dead. Yet in almost every instance, Wright’s poems are used to illustrate her experiences, beliefs and above all the development of her lifelong concern for the environment and the plight of Australia’s original inhabitants. Their status as poetry is hardly if ever considered.

For many of Wright’s admirers, among whom I must include myself, that would seem a sad reversal of priorities. The only way in which I can make sense of the scope and ambition of this long and minutely detailed study is to read it as an account of Wright’s emergence from her family’s solid, largely conventional pastoralist background into a committed conservationist and champion of Aboriginal land rights. In the course of that journey writing poetry seems, at least in Brady’s account, to have retreated into the background – a sentiment Wright herself confirmed in several statements and comments quoted in South of My Days. In the latter half of her career most of her energies seemed to have been taken up by committee work, by meetings, conferences and action groups all devoted to the imperatives of an increasingly apocalyptic view of contemporary society – acquired in part, no doubt, from the philosophical inclinations of her husband, Jack McKinney.

Brady – and by implication Wright herself – may be correct in their implied estimate that the problems of the modern world are too pressing for poetry. If the fragile fabric of the earth is under immediate threat, if we Australians lead our daily lives in the shadow of an. obscene injustice against those whom we dispossessed and brutalised, then poetry may well be mere frippery – or else justified only when serving higher ends.

On the other hand, much of the verse quoted in these pages transcends the inevitable simplicities of propaganda – no matter how morally justified and responsible such propaganda might be. The opening lines of ‘Australia 1970’

Die wild country, like the eaglehawk,

dangerous till the last breath’s gone

clawing and striking. Die

cursing your captor through a raging eye

may, as Brady states, have been ‘inspired by the sight of the brigalow country ... being cleared by bulldozers and tractors with chains’, yet their fierce passion and Old Testament eloquence raise the poem to a higher, more abstract and general plane of significance than Brady’s self-imposed limits are capable of embracing.

I see two particular consequences flowing out of the methods adopted here. One is the avoidance of the evocative. Brady’s writing is clear, serviceable, if at times a little wordy, a fit instrument for incorporating galaxies of detail – about bureaucrats, politicians, meetings, manifestos, campaigns, congresses and the like, and also broad historical and political circumstances. It is, in short, the type of diction one would expect to find in the biography of a public figure.

The other consequence is, for me at least, more troubling. Brady is, I suspect, too close to her subject. South of My Days admits almost no dissent. It demands wholehearted agreement with its clear division of the world (or at least of contemporary Australia) into those who have seen the light and those – right-wing politicians, mining magnates, property developers – who dwell in perpetual darkness. To take but one minor instance: Wright’s campaign in the early 1970s to prevent Concorde flying over Australian soil is accorded the same weight, respect and importance as her participation in other, to my mind much more important, ecological issues. It pains me to say this about Brady, whom I like and respect, but having reached the end of South of My Days I was left with the sense that her enthusiasm for Wright’s enthusiasms has prevented her from striking that indispensable critical distance which every biographer needs.

Comments powered by CComment