- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A white-haired, white-bearded Captain George Bayly peers benignly out at us from the 1885 photograph frontispiece of A Life on the Ocean Wave. With epaulettes to his black uniform jacket, braided sleeves, a sword at his side and a ceremonial captain’s head-piece on the table beside him, Bayly looks the quintessential retired man of the sea. He looks like a man Charles Dickens should have been describing. We should be meeting him in some sea-side parlour, in some sailortown tea-palace. He looks as if he has a story to tell.

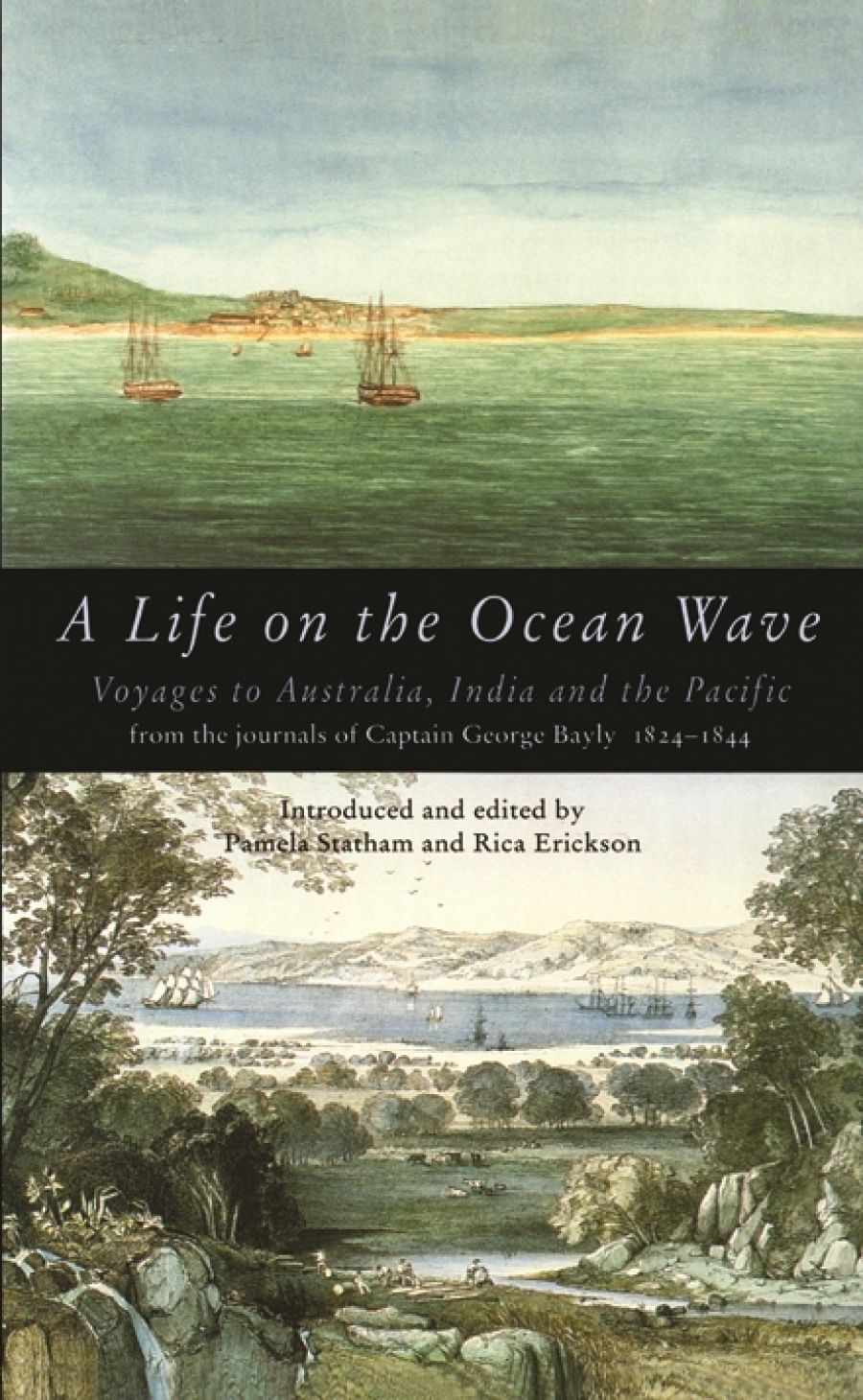

- Book 1 Title: A Life on the Ocean Wave

- Book 1 Subtitle: Voyages to Australia, India and the Pacific from the journals of Captain George Bayly 1824–1844

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $49.95 hb, 364 pp

Indeed he does. Many stories. 350 pages of them, twenty years of them, eleven voyages of them. From 1824 when he signed on as apprentice to Captain George H. Boyd on the Almorah, to 1844 when he signed off as captain and owner of the Hooghly, Bayly writes journals. These are not the ordinary coded telegraphics of seamen’s logs. These are discursive reflections on the closed-down environment of a ship and all those foreign environments to which the ship takes him.

Bayly is no Pacific explorer and discoverer. He is an Atlantic, Indian Ocean, China Sea, Pacific, Australian waters mover of people and things. Sometimes he is on the edge of great historical events. He is at the beginnings of the Opium War in China. He holds the sword of the lost la Pérouse when the wild man, Captain Peter Dillon, is first given it by the islanders of Vanikoro where la Pérouse had been wrecked.

Mostly Bayly is like a cork bobbing along in the ebb and flow of the great people movements of the first half of the nineteenth century. The flow is the peopling of the Australian continent with convicts and free settlers, with men, women and children, with the animals – horses, cattle, sheep and dogs – that energised their settlement, with the artefacts and materials with which they built it. The ebb is the trickle back of trade through the run-offs of Calcutta, Batavia, Singapore, Madras, Mauritius, Canton, Macao.

The sea and the sky are always the backdrop to Bayly’s stories. The sea – in flat calm, in terrifying force, in magical moments of phosphorescence, playfully beautiful in its primitive state with myriads of dolphins, whales and fish – the sea is enemy, friend, servant, master. The sky in its winds and clouds is the constant portent of tomorrow.

Bayly is no poet, nor philosopher either. But since he has to manage the behaviour of men and women constantly in stress with one another in the confinement of a ship, he is a good observer. He is seeing things that will fascinate anyone interested in the making of new worlds. From off the beaches, he sees the new settlements of Swan River and· Bunbury in Western Australia, Port Adelaide in South Australia and Williamstown in Port Phillip Bay. They were raw, tough places, even places of Hobbesian tooth and claw. He has to cope with Scottish shepherds and their most precious asset, their thirty ‘collie’ dogs. He has to cope with a colonel of a regiment who goes bizarrely and religiously mad. The colonel is always trying to jump overboard, Bible in hand, hoping to be swallowed by Jonah’s whale. Then he is studiously and serenely sane the day they arrive in Sydneytown. There are ranting fundamentalists on Bayly’s ships, drunken, vindictive commanders, births by the handful, deaths by the dozens. The reader can follow trips from London to Swan River, Sydney and Adelaide on ships filled with more than three hundred convict women, more than three hundred free emigrants, and won’t know in the end which is worse.

Bayly’s journals are edited, with modest intrusions, by Pamela Statham and Rica Erickson, from unpublished manuscripts held by New Zealand’s University of Otago. The University also holds eleven of Bayly’s own watercolours of his ships and the places they visited. They are reproduced in full colour. As are some dozen other pertinent paintings. This is a Miegunyah Press production. So it is lavish. There are sixteen maps that make it more so. There is even the Miegunyah Press signature, a bookmarker ribbon.

The reader will need the ribbon. This is no one-sitting book. The editors insist that they have culled about a fifth of the original manuscripts. There are times when a reader will wish that they had culled more. Or rather, the reader will wish that the editors had swapped some of Bayly’s repetitious account for a bit more history of their own. Each of the eleven voyages is introduced by a bare summary of its details. The editors keep the contextual knowledge they obviously have pretty close to their chests. The consequence is that the reader is dragged along rather myopically on Bayly’s adventures. Bayly’s voyages are much larger than themselves. They give flesh and blood, pain and pleasure to a much larger story of maritime trade, people’s movements and the foundations of societies. This reader, at least, wanted some guidance as to what that contribution is.

Comments powered by CComment