- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Clarity and mastery

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Clarity and mastery

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Commendations from celebrities and authorities have become a standard feature of cover designs for books of poetry: sometimes one wonders whether the writers have actually read what they puff so assiduously. How refreshing it is, then, to find Clive James and August Kleinzahler recommending Stephen Edgar’s latest volume so perceptively. Kleinzahler’s phrase ‘voluptuous elegance’ goes to the heart of Edgar’s way with words. James’s comment will strike a chord with anyone who takes the time (and time is needed – these are not poems to skim through) to engage with Other Summers:

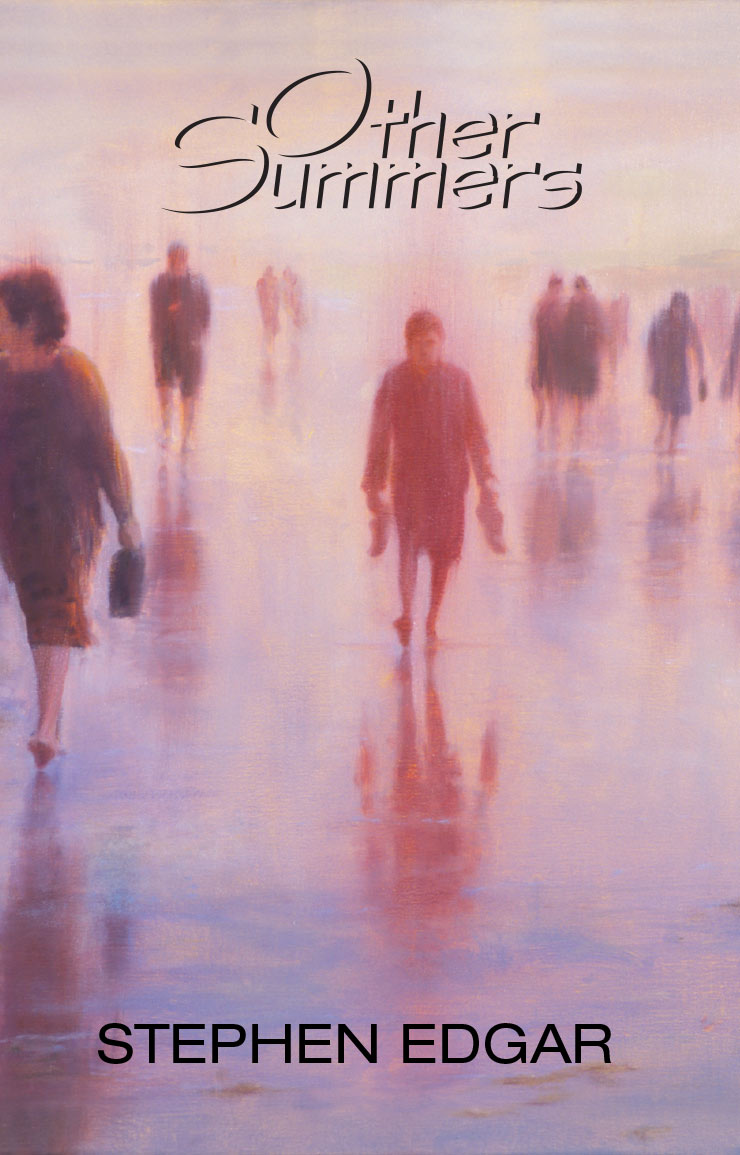

- Book 1 Title: Other Summers

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Pepper, $23.95 pb, 108 pp, 1876044543

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

… perhaps the most fascinating aspect of all is that under the enchanted lyricism, the technical intricacy and the dazzling vocabulary there is always the bedrock of good, plain, conversational speech.

Not surprisingly, the opinions of one poet about the work of another surpass or at least precede the evaluations of academic critics. Years ago, Edgar’s close friend Gwen Harwood took me to task for not knowing more about Edgar’s work than I did. ‘Read that!’ she said, presenting me with Queuing for the Mudd Club (1985) – ‘everyone should know about Stephen!’ Until recently, Edgar’s poems were not well known, except to other poets. He has not been someone to put himself about at literary festivals and readings, at least not outside Hobart, where he lived for thirty years until his recent move to Sydney. Edgar’s seclusion may have nurtured his great gifts, but one hopes that soon his work will reach the wide audience it deserves. Like Harwood, he is a wonderful reader/interpreter of his own work: that ‘bedrock of good, plain, conversational speech’ was strikingly present in the readings he gave at this year’s Mildura Writers’ Festival, where he was awarded the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal.

The language of the poems in Other Summers is striking in its range, from colloquial plainness (as in ‘English as a Foreign Language’), as the speaker tells of teaching his lover to say ‘“I love you” in Russian’:

A lover’s commonplace avowal

But rather difficult to sound

In Russian; it can be a trial

To get your tongue around.But she repeated those words over

And over till she had them pat.

In English, though – well, she could never

Quite manage to say that.

Only an exhibitionist or an artist firmly confident of both his medium and audience would dare to use words such as ‘proprioception’, ‘anfractious’, ‘embowment’ and ‘stridulent’. But Edgar is no exhibitionist. The movements into the register of such polysyllabic arcane diction have the effect of jolting the reader into thought, making us ponder the strange materiality of these words in their poetic contexts. How many of us have forgotten the peculiar delight of encountering a new and strange word, going to the dictionary to check its meaning and etymology, and then committing it (or not) to memory? Such language is sparingly and economically invoked; many of the poems reflect their creator’s erudition, but the effect is never intimidating, because of the seductiveness of the voice and the sheer power of Edgar’s vision.

‘Proprioception’, which introduces the second of the volume’s four sequences, is a case in point. The word is used only for the title, but knowing what it means adds a dimension to the poem’s layered meditation on the subjectivities of balance. It moves from an exquisitely precise and witty picturing of ‘kids on skateboards’

as they careen,

Curvet and caracole

A wheeled mock dressage through, between,

Among pedestrians and keep their hold –

Or sprawl in a four-letter wreck and roll,

to the self-abandoning moment of rapture when the speaker looks up to experience the aerodynamic mystery of a wheeling crane, and thence downward and inward, to his reflection on the dynamics of grief and loss: ‘Still at the empty table you make space / For where she sat and tread the kitchen’s bounds / As though two wrote that choreography …’ This elegiac voice is the dominant one in Other Summers. Characteristically, the sense of a striving for detachment is heightened by the use of the second person, where we might have expected ‘I’. It is difficult to be certain, sometimes, whether those ghostly presences, which are more real to their creator than his sense of self-identity, are actually or figuratively dead to him. Does it matter? That the reader wishes to know something that is withheld is testimony to the way these poems embody the absent lover, whether through the loving observation of the known body in ‘The Immortals’,

Look, on her hand’s back are the clues to grief,

Whatever she may think – those patches like

The remnants of a suntan, veins as blue

As any sky could wish …

or the finely tuned eroticism of ‘The Kiss’:

And that first night you slid the purple shift

Over her shoulders and

Peeled gently downwards, leaving her to stand

In Aphrodite’s gift,

And sinking with her garment to the floor,

Made moist the shining fold you knelt before.

This is one of a suite of ten poems called ‘Consume My Heart Away’; at a first reading, I did not appreciate the intricate patterns of theme and image which run through the whole. The human inhabitants of this summerworld sometimes appear almost incidentally, as in ‘The Sounds of Summer’, which begins with a bravura piece of synaesthetic description. This way of embodying the natural world in all its sensuous particularity seems to owe something to Harwood’s exploration of the language of nature in ‘Carnal Knowledge’ and in her late Pastorals.

Edgar’s work shows a Romantic fascination with colour, shade and light, and with the challenge of recreating them through language. I almost missed the moving tribute to Harwood, in ‘Living Colour’ (‘Just as the poet said she’d thought her home, / The blessed city, till she was born to bless it …’). This remarkable poem explores the idea of colour as a way of lifting fascism out of a monochrome past into the technicolour present, where its power is seen in all its sinister immediacy.

This is some of the finest lyric poetry to have been written anywhere in recent times. Through sound and structure, Edgar’s work reflects lessons learnt from music as well as from poetry: there are echoes of a range of singing masters, from Dante to Donne, from Larkin to Hope and Harwood. Perhaps the first thing which strikes the reader is his sheer delight in form, structure and rhyme.

Old-fashioned? Surely not, for in most of these poems form exists in delicate equipoise with a passionate and highly individual vision of the world. The range of this vision is impressively wide, from the elegies for lost lovers to gentle tributes to parents, from political and social satire to gazes into the realm of nightmare. The poems from ‘The Labyrinth’ invert the experience of quotidian space and time, re-seeing the familiar and the known as though from another dimension, envisaging the horror of dis-integration. Here, as elsewhere in this volume, the irruption of an arcane word into the line of plain speech jolts the reader’s sense of security in the reading process, drawing him into the experience of the speaker:

An empty flask, a ragged coat laid by,

A notebook or a mobile telephone.

At some point all apparently surrendered

To the anfractuous fallacy and turned

Leftwards or right to seek the fabled zone …

Stephen Edgar’s writing is analogous to the activity of the photographer in ‘Photography for Beginners’: both have the ability to fix and freeze the apparently ordinary moment, to subject it to a gaze which renders it strange, and so impels the viewer/reader to ponder the contingency and fragility of the very act of recording. The difference, of course, lies in the humane clarity of the poet’s vision, and in his mastery of an art of multiple perspective.

Comments powered by CComment