- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: A fight in a pub

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A fight in a pub

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 18 January 2004 the Victorian cricket team defeated South Australia in an ING Cup match. After the game, some of the cricketers and officials, including the Victorian coach David Hookes, and their girlfriends, assembled at the Beaconsfield Hotel, in St Kilda. Hookes had played twenty-three test matches for Australia between 1977 and 1986, at an average of 34.36 runs. After retiring as a player, Hookes, beside his coaching duties, had carved out a successful career as a broadcaster and media commentator. As closing time approached, security staff informed the group that it was time to leave. Approximately fifteen minutes later in the car park, Hookes received a punch from security guard Zdravko Micevic, and fell and hit his head on the ground. He died in the early hours of the next morning. Micevic was charged with the crime of manslaughter, but was subsequently acquitted by a jury on the grounds of self-defence.

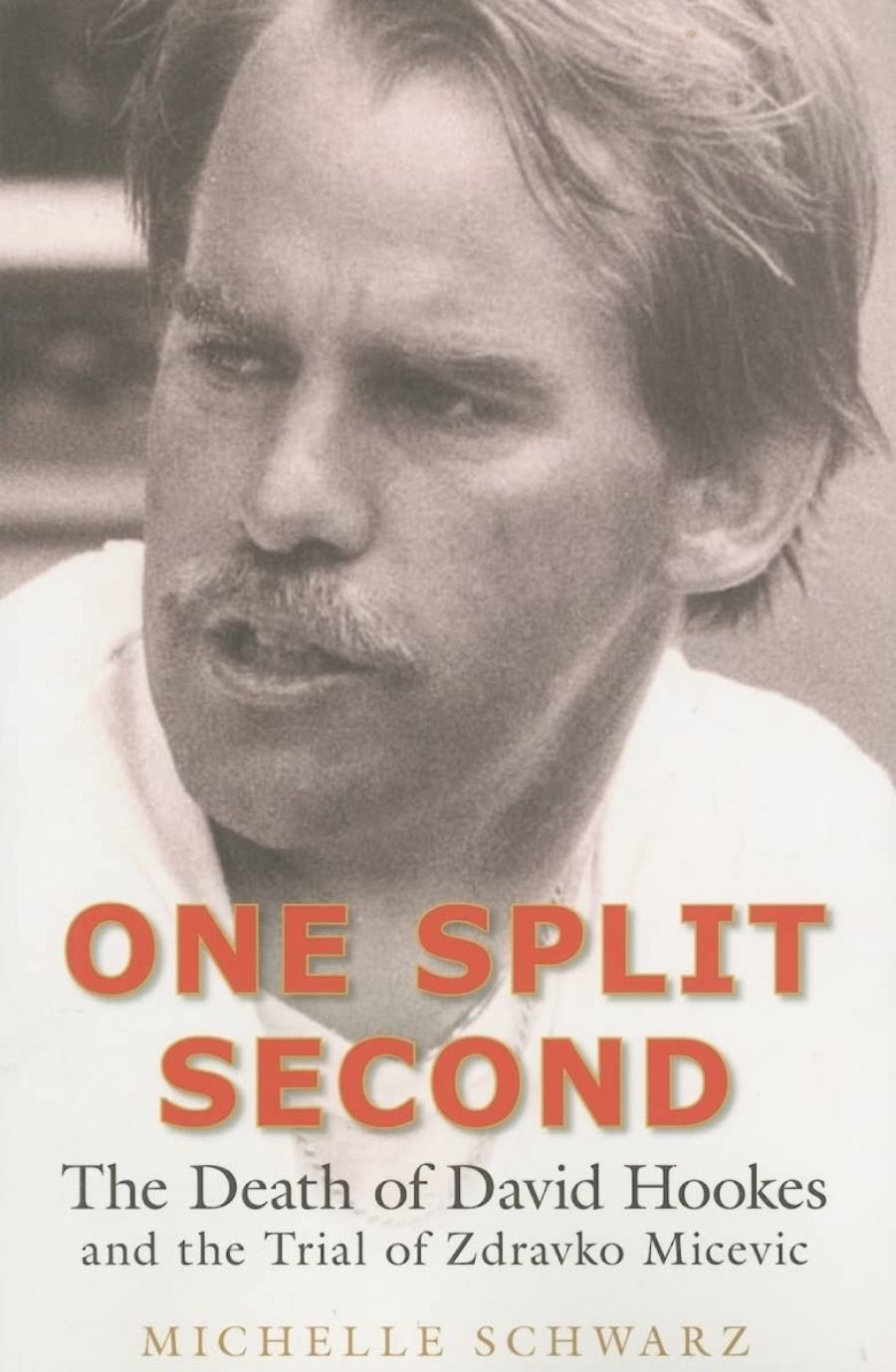

- Book 1 Title: One Split Second

- Book 1 Subtitle: The death of David Hookes and the trial of Zdravko Micevic

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $34.95 pb, 234 pp, 0868409472

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

A memorial service was held at the Adelaide Oval, screened live by Channel Nine, free of advertisements. In posters and other forums, many people who had never met Hookes expressed how saddened and devastated they were by his death. Similar expressions of loss occurred with the deaths of the herpetologist and zoo owner Steve Irwin and racing car driver Peter Brock, but not the politician Don Chipp or playwright Alex Buzo. Michelle Schwarz became fascinated by this outpouring of public grief for a celebrity. She was moved to investigate Hookes’s death and the significance of events surrounding it in providing a window into Australian society.

One Split Second, though not a long book, contains forty-seven chapters. Schwarz combines documentary sources, interview material and more philosophical musings about Hookes’s death and Micevic’s subsequent trial. She did not include some of the interview material, because they were too exposing in their expressions of grief. The respective chapters examine one or two issues in a clear and straightforward manner.

First and foremost, Schwarz provides an account of the workings of Australian courts and the legal system. The prosecution claimed that Micevic had been the aggressor, and had pursued a blameless Hookes before hitting him with that fatal blow. The defence claimed the opposite: the cricketers, led by Hookes, had initiated the hostility, and Micevic, after being punched twice in the stomach by Hookes, threw a punch in self-defence, which unfortunately resulted in his death. Hookes had a blood alcohol reading of 0.14, almost three times over the legal driving limit. Schwarz quotes an expert who maintained that, because of the amount of alcohol he had consumed, Hookes’s senses were dulled and he was unable to react in time to protect himself from the fall.

Schwarz explains and demonstrates the manner in which rival barristers mount their sides of the case and the devices they utilise in breaking down the evidence of hostile witnesses. In evidence that Schwarz describes as being ‘like gold for Micevic’s defence team’, Wayne Phillips, coach of the South Australian side, testified to the less than perfect behaviour of the cricketers in general, and Hookes in particular.

Special praise is directed by Schwarz to Detective Senior Sergeant Charles Bezinna, the investigating officer in charge of the case, for the respect and decency he displayed to each family and party involved in the case. Bezinna was acutely aware of the misery and suffering experienced by everyone involved. He helped to allay the fears of witnesses prior to testimony, and advised Micevic’s father on when it would be best to approach Hookes’s brother, Terry Cranage, to express his regret and sorrow for what had happened. One of the most moving paragraphs in One Split Second has the two men shaking hands after the verdict was handed down, and Micevic gently placing his hand on Cranage’s shoulder.

Schwarz draws attention to alcohol as an insidious but important part of Australian and cricket (if not other professional team sports) culture. She reproduces data showing that, in 2003, 135 people died in assaults where alcohol was a factor. Each year, there are 3500 alcohol-related deaths, and 85,000 people hospitalised from alcohol-related injuries. While hoping that something will be done to counter Australia’s problems with alcohol, Schwarz is keenly aware of how difficult it would be to challenge the power of the alcohol industry, and laments its extensive sponsorship of sport.

The media played a major role in shaping the public mind following Hookes’s death. Being one of their own, Hookes was portrayed as a paragon of virtue and Micevic as the devil incarnate. Approximately a year before his death, Hookes had separated from his wife and acquired a new girlfriend. According to Schwarz, he had other love interests. In the immediate aftermath of his death, most elements of the media sought to maintain the fiction of Hookes’s happy marriage. This deceit was eventually exposed by Melbourne broadcaster Derryn Hinch.

More significant was the vilification of Micevic. At one stage, Schwarz says, ‘As I read through newspapers and transcripts of radio shows, I increasingly had the image of an animal trainer throwing chunks of meat to a pack of hungry feral dogs. The media was catering to the most prejudiced and base sentiments in the population.’ She also refers to the biased reporting during the trial: negatives concerning Micevic resulted in headlines, while negatives about Hookes ‘barely received any coverage at all’. Micevic was the target of hate mail and death threats (his legal team also received death threats). His car was vandalised and the family home firebombed. He and his family were forced to move. Schwarz maintains that race – the fact that the cricketers were Anglo-Saxon and the security guards recent migrants living in Melbourne’s western suburbs and earning low wages – was the elephant in the room that no one wanted to see.

Schwarz has a twofold explanation for the public expression of grief following Hookes’s death. The first is sociological in orientation. Persons and leaders who ‘we’ traditionally trusted have been found to have feet of clay. There is no longer a sense of community. Society has become what sociologist Emile Durkheim would describe as anomic; that is, dominated by a sense of normlessness. People feel a need to believe in someone or something. In Australia, such reverence is given to sporting personalities. David Hookes fitted this bill. His death was strongly felt by many, and the collective grieving it prompted created a sense of community. The dark side of this feeling was the vilification of the person seen as responsible for his death.

The second explanation is psychological. Schwarz maintains that the death of a celebrity, especially in tragic circumstances, brings home to us our own vulnerability; the sense that life is subject to random events beyond our control. This conclusion, and her attempt to distil the meaning of the human experience, is the least convincing feature of One Split Second. Throughout our lives we all experience the death of a friend or a family member, many of whom die ‘before their time’. We are upset by such events not because of our own mortality but because these people no longer figure in our lives. This is nowhere better illustrated than in the various interviews Schwarz conducted in researching this book. The anguish expressed by those close to Hookes – especially those who were present on the night of his death, including Micevic – typifies the way those ‘intimately’ associated with death endure its tragedy. Schwarz’s ability to capture this is what gives One Split Second its special edge.

Comments powered by CComment