- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Displaced heroes

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Displaced heroes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Adrian Hyland spent many years living and working among indigenous people in the Northern Territory. His affection for and affinity with the people and the country are immediately evident. But whatever possessed him, in his first novel, to write in the voice of a young, half-Aboriginal woman? It is a testament to his skill and finely balanced writing that more has not been made of this fact, and that the reception to his novel has been mostly positive.

- Book 1 Title: Diamond Dove

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $22.95 pb, 330 pp, 1921145307

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

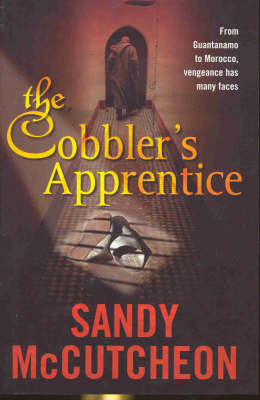

- Book 2 Title: The Cobbler's Apprentice

- Book 2 Biblio: Scribe, $32.95 pb, 416 pp, 1921215003

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Could it be Blakie, the crazy, crystal-worshipping sorcerer who lives on the fringes of the Moonlight Downs community – or Earl Marsh, the owner of the neighbouring Carbine Creek Station, who is intent on acquiring the community’s land? Impetuous and fearless, Emily storms through her investigation, hurtling through the town and aggravating people.

Hyland’s depiction of the Warlpuju people of Moonlight Downs is sensitive and respectful. He goes to meticulous lengths to draw the line between what is real and sacred, and what is a figment of his own imagination. He does a wonderful job of describing the rhythm of life in the Moonlight Downs community, as well as the rough realities of the near-by town of Bluebush, where racism and violence mix with liberal amounts of alcohol.

The land itself is at the centre of the novel; not only because its ownership is the catalyst for murder. Emily’s father, Jack, has passed on to her a fascination for rocks and topography, while her childhood friend Hazel shows Emily how her people are connected to the land and how to approach its mysteries through their Dreaming.

The painting was earth-coloured, ochre washed, with wings and wheels and white flowers. But shot through with the odd bolt of blue-grey, like the blurred image of a diving bird …

So deftly had the arrows been incorporated into Hazel’s design that they looked like the tracks of some ancestral being.

‘This is so amazing, Hazel. What is it?’

She came up beside me, her bare feet padding over cool stone.

‘Don’t you recognise it?

‘Should I?’

‘Diamond dove,’ she whispered.

Diamond dove. Again. The dreaming and its multitudinous manifestations – people and places, creatures, songs – was [sic] beginning to emerge as the motif of my return to Moonlight.

With all these different threads woven into the narrative, Hyland still manages to keep our attention firmly on the feisty Emily. Being situated between two cultures makes her the object of suspicion and misunderstanding from both sides, but in the course of her novel she starts to understand more about how this conflict is positioned in her own life, and how she can make peace with it.

Her relationships with Jack and Hazel are the most intriguing of all, full of unsaid things and unwritten rules, but the novel is peopled with compelling characters. Sometimes they don’t sound quite right – ‘Same obstreperous little bugger you always were’, the local policeman says to Emily – but for the most part they are well drawn, making for involving, engrossing reading.

The same cannot be said for The Cobbler’s Apprentice. This is unfortunate, because Sandy McCutcheon has written a novel with a fascinating premise, one that is quite plausible in the current political climate.

Samir Al-Hussaini, a young Palestinian boy, has escaped from Guantanamo Bay, aided by two inmates he thinks are fellow jihadis. Sent to Cuba for training, Samir is then transported to Morocco, where he is to ingratiate himself with a ‘traitor to the cause’, known to him only as Moul Sebbat. Once he has infiltrated Sebbat’s inner circle, Samir is meant to assassinate him, using himself as a human bomb. But things go horribly wrong for Samir’s minders when he discovers that he is being manipulated by Mossad and the CIA, and turns the tables on them. What he does next makes for chilling reading, giving us a whole new way of looking at the term ‘weapon of mass destruction’.

My biggest struggle with this novel was that, despite being billed as a thriller, its pace was surprisingly lethargic; the intricately plotted narrative unravelling much, much too slowly. Most of the book is given over to McCutcheon’s skilful scene-setting (perhaps a legacy of his playwriting career). He has obviously spent a lot of time researching his facts, but he is so intent on describing the details of the plot that the action loses momentum and any sense of urgency. This in turn makes the characters fade into insignificance. McCutcheon does try to flesh them out, but they are always completely secondary to the story. It becomes hard to care about or be compelled by them; when some of the ‘good guys’ die, it barely produces a ripple in the narrative.

Samir, riddled with doubt one minute, coolly intent on destroying his deceivers the next, is by far the most well-rounded character. He is a child who has grown up too fast, encouraged to become a martyr like his brother, trying to reconcile his religion and his political situation with his feelings of fear and regret. I would have liked to know more about him, but the more two-dimensional characters constantly diverted attention away from him.

This is all the more regrettable because the events that transpire and the scenario McCutcheon is positing are topical for contemporary readers and should garner more of an emotional response. The political machinations are believable enough, but without any compulsion for the reader to be involved in the story, reading becomes a purely intellectual exercise.

To a large extent, Emily and Samir are the victims of their situations; the violence they are exposed to comes from external exploitation and manipulation. The worlds they inhabit contain people who have no qualms about using brute power and deceit to gain the upper hand. They respond to this reality in vastly different ways, but in both there is an inner conflict born of displacement.

In Hyland’s Emily, that conflict is explored as much through her previous history as through her present adventures and relationships. In contrast, while the genesis of Samir’s anger and his evolution into a jihadi are equally well charted, the depiction of his transactions with other characters lacks depth. Ultimately, these protagonists’ interactions with secondary characters make the difference in their effectiveness and emotive power – and consequently in the novels themselves.

Comments powered by CComment