- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Scholar and patriot

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Scholar and patriot

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the eve of the recent history summit, Education Minister Julie Bishop told an audience, which included some notable historians, that history was not peace studies, nor was it ‘social justice awareness week’, nor, for that matter, ‘conscious-raising about ecological sustainability’. History, she declared, was simply history: though when she went on to assert that ‘there was much to be proud of in the history of Australia’, it did seem that she might have an agenda of her own tucked away in her ideological handbag

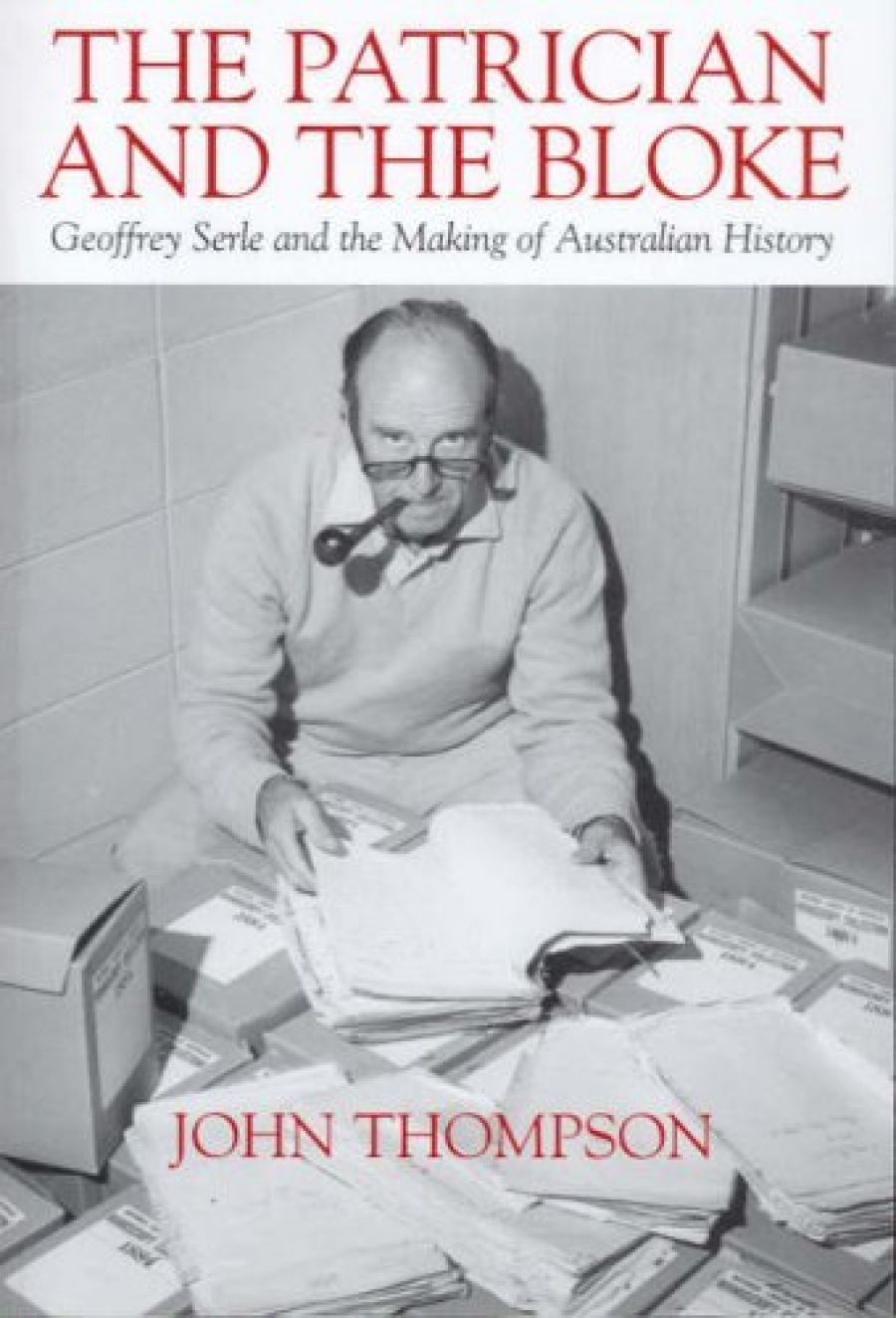

- Book 1 Title: The Patrician and The Bloke

- Book 1 Subtitle: Geoffrey Serle and the making of Australian history

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $34.95 pb, 397 pp, 1740761529

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Geoffrey Serle (1922–98) has been hailed as ‘the doyen of Victorian historians’, a description which, while he would have appreciated the compliment, might have irritated him, as he very much identified himself as an Australian. Thompson places him in the context of a cohort of historians, products of the Melbourne University History Department, who were among the pioneers in the evolution of Australian history in the universities and schools after World War II. The influential Max Crawford, assisted by Kathleen Fitzpatrick (whose stylish lectures were legendary), had done much to shape the intellectual culture of the department, and after the war they were joined by the young Manning Clark, who taught his first Australian History course there in 1946. Serle, a student in that class, was captivated. Other future historians to fall under the spell of Clark included Ian Turner, Hugh Stretton, Ken Inglis and Geoffrey Blainey. In 1950 Serle, returning from Oxford, joined the department and in the following year took over the teaching of the Australian History course that Clark had placed his stamp on. In 1961 he made the academic journey to the newly founded suburban Monash University, where John Thompson, like myself, was to be one of his students. The lineage from Crawford to Clark to Serle and his Melbourne contemporaries, and the colonising thrust to Monash, were to become part of the mythology surrounding what became known, rather grandly, as the Melbourne School of History.

Serle grew up in suburban Hawthorn, and, apart from the interruptions of war and Oxford, he was to live there for most of his life. Indeed, he was known to say in jest, ‘Stuff Victoria and Melbourne, I am an Australian and a Hawthorn man’. His father, Percival, was a literary figure, whose major achievement was the two-volume Dictionary of Australian Biography, published in 1949, while his mother, Dora, was a painter of some distinction. It could be said that he chose his parents well, finding himself, the youngest of three children, in a lively household where culture was taken for granted. Scotch College, under its enlightened headmaster Colin Gilray, made its contribution, giving him what he described as ‘a good and demanding education’.

After one year at the university, the army snatched him up. He declined the Duntroon option, and was content to serve as ‘cannon fodder’ in the Signals Corps. By 1943 he was in New Guinea and had risen to the exalted rank of corporal. But later that year he suffered a severe shrapnel injury, and after a slow recovery returned to civilian life in mid-1944. Whatever tedium and suffering war service had inflicted on him, Serle was to rate the army experience of ‘knocking around’ with men from all walks of life as a vital part of his education as an historian. As one of the cohort of ex-servicemen who stormed the battlements of Melbourne University at war’s end, he threw himself into the maelstrom of radical student activism with a newfound confidence. Thompson characterises him as ‘solid rather than brilliant’ and ‘a man of conscience and principle and a good citizen of his university’. It was ‘a time of personal flowering’. A Rhodes Scholarship took him to Oxford in 1947, and on his return the career unfolded with what, in retrospect, might look like inevitability, but which, at the time, had its uncertainties.

Oxford is a case in point. At a time when postgraduate studies had little presence in Australian universities, the progress to Oxford, Cambridge or, at a pinch, London was a natural one for young scholars. However, Serle, eager to immerse himself in research, rather ambitiously decided to enrol for the DPhil in preference to the more usual choice of a tripos degree. He enthused about the subject of his thesis to his friend Stephen Murray-Smith: ‘It’s going to be great fun – bodyline, news coverage, Bruce’s spats, Jack Lang & the bondholders, Egon Kisch etc. Brit.–Aust. relations 1919–1939, theme Australian nationalism.’ In the wake of World War II, it was a timely subject, and it already foreshadowed Serle’s later investment in what came to be known as the radical nationalist tradition, but with all the diversions of Oxford life and the temptations of travel, he found himself in a rush to complete the thesis. His examiners had reservations about the finished work and suggested he resubmit. It was a blow, but he accepted the challenge and reworked the thesis, winning the examiners’ approval . The experience encouraged a certain diffidence in Serle about the quality of his own work; he confessed that his subject ‘needed a subtler pen than mine’.

The thesis was never published, which is a pity. As Thompson remarks, in exploring ‘the landscape and the permutations of Britishness in Australia’ it broke ground ‘that has remained too little worked, partly for reason of fashion and partly because other questions assumed greater urgency’. One needs to be reminded that Serle was writing during the era of those streamer-festooned farewells at the wharf, when the great white liners bore us from our provincial outposts to the cultural metropolis. The Stratheden on which he sailed was also carrying, in seven crates, the ingredients for Princess Elizabeth’s wedding cake, a gift from the loyal Girl Guides of Australia. It is nice to imagine that Norm Everage, who, as Edna has often told us, was in dried fruits, might have had something to do with that.

Once established in his academic career, Serle turned to the other half of the British equation, researching the character and impact of the gold-rush generation of immigrants on the infant colony of Victoria. The result was The Golden Age (1963), which affirmed the individuality of the Victorian experience. Gold had remade the colony and peopled it ‘with men of more diverse talents, skill and backgrounds, and perhaps more vigour, than Australia had yet seen’. It was a theme he returned to in The Rush To Be Rich (1971), which, evoking the heady extravagance of 1880s ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, argued that historians had tended to gloss over the distinctiveness of each colony’s history. At a time when a national brand of Australian history was staking its claim in university and school curricula, this had the character of a dissenting judgment, but it contributed to the developing interest in regional history. But here, too, Serle was modest in the claim he made for these two major works of colonial history, characterising them in pioneering terms as clearing the ground for future work. Similarly, with From Deserts the Prophets Come (1973), which sought to bring high culture into the general discourse of Australian history, he emphasised his dependence on the works of Bernard Smith, H.M. Green and others, at the same time almost apologetically offering the book as ‘a rudimentary attempt at a theory of cultural growth’.

His monumental biography of that monumental figure John Monash (1982) took him into new territory. Serle had had a long association with the Australian Dictionary of Biography, serving as general editor from 1975 to 1988, but Monash, a complex figure who had left a dauntingly large collection of private papers, offered a unique challenge. The biographical pursuit continued with a very different subject in Robin Boyd: A Life (1995). Thompson argues that part of the attraction of Boyd for Serle was that he was a member of his own generation who had, like him, served in the war, and, although approaching cultural history through the medium of architecture, shared many of his own liberal, humane values. His final salute to Boyd was as ‘an inspiring public intellectual and patriot’.

Serle, too, was undoubtedly a patriot in the best sense, but one who was frustrated by what he called ‘Australia’s amble towards nationhood’. He was not, however, a media-savvy public intellectual in the manner of Boyd – that was not his style – but rather an active and committed contributor to a number of causes and institutions of concern to a conscientious historian: the then down-at-heel State Library, the development of archives, the National Trust and what is today called ‘public history’, and literary journals such as Meanjin and Overland. Nor was he personally ambitious in the academic context. Once he had gained a readership at Monash, a position suited to his research bent, he does not appear to have ever applied for a chair. (This is one aspect of Serle’s career not explored by Thompson.) Indeed, he caused some controversy when he inveighed against the cult of the ‘God professor’.

Thompson remarks on Serle’s ‘odd mixture of stubbornness and diffidence’, and characterises him as being shy and emotionally reserved. This reticence may have been a factor in the ‘notorious silences’, which were an unnerving feature of his tutorials and seminars, when his apparent retreat into himself would sometimes drive a student into nervous babble to fill the threatening void. In fact, I suspect he was unaware of the effect he created and was simply reluctant to speak before he had thought through his position. On the other hand, as I and others can testify, he was a thoughtful and supportive supervisor, and not at all intimidating.

He was, of course, a man of the left, though he was never tempted, as were his contemporaries Stephen Murray-Smith and Ian Turner, to join the Communist Party. Turner, who also came to Monash, makes for an interesting comparison. He was the charismatic teacher who took up the cause of popular culture (his Ron Barassi Memorial Lecture on the eve of the VFL grand final became a much-publicised Monash event), but who was also, in his post-communist days, active in the Centre Unity faction of the Labor Party. Serle was the dogged researcher and writer who had left behind the activism of his student days, preferring instead to devote himself unobtrusively to the historical and cultural causes close to his heart.

Much as Serle always expressed his debt to Manning Clark, there was, as Thompson observes, an ambiguity in their relationship. In a 1975 essay, ‘Writing History in Australia’, Clark invoked the house in Ibsen’s The Wild Duck as a metaphor for characterising and locating the writers of Australian history. He identified some historians as being photographers like Hjalmar and Gina, who inhabited the first floor of the house, as opposed to those who, thirsting for deeper truths, sought refuge in the loft with Hedwig and the wild duck. Clark thought that both Blainey and Inglis had spent some time in the loft (which, we can safely assume, Clark saw as his own home), and he hazarded that Turner, even if he didn’t realise it himself, really belonged there too; but Serle he categorised as a photographer, along with Margaret Kiddle and Marnie Bassett. He acknowledged him as ‘a great Victorian patriot’, but the implication was that his history lacked imagination. It was a patronising judgment and perhaps took Serle’s self-deprecatory estimation of his own works at face value (though, to be fair to Clark, this essay was written before the publication of John Monash).

In this impressive intellectual biography, Thompson’s tone is measured and judicious, an appropriate response to his subject’s disposition. At all times, he strains to be even-handed in his critique. In the end, he sees Serle’s best qualities as being his restraint and his decency. Some of the criticisms, such as relating to his uneasiness with feminism, may seem predictable enough. But emotional reticence may also have contributed to the lack of ease and sympathy Thompson sees in his biography’s treatment of Monash’s relationship with his mistress, Elizabeth Bentwich. Serle’s own defence was that he was ‘reluctant to give new life to the tradition of prurient gossip’ that had surrounded the relationship, which could be seen as an interesting example of how his sense of restraint and decency was played out.

The Patrician and the Bloke – the title nicely capturing the polarities of Serle’s persona – also serves to remind us that the 1950s was not the sterile decade that has sometimes been depicted. It was a time of much intellectual activity, even ferment, and the opening up of the virgin landscape of Australian history as a subject for study was part of that experience. Looking back, we might envy Geoffrey Serle and his contemporaries the excitement of those pioneering forays into the mysteries of Australia’s past.

Comments powered by CComment