- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘As far as books are concerned, I find life no help at all. Books grow out of other books.’ So said the great Ivy Compton-Burnett, and her comment is at least partly pertinent in relation to Lloyd Jones’s luminous Mister Pip, trailing as it does clouds of Dickensian glory. Increasingly, there seems to be a sub-genre of novels that have their roots in other novels. Some of these are vile, like Emma Tennant’s vulgarly opportunist Pemberley Revisited: or Pride and Prejudice Continued (2005) and Emma in Love (1996), which traduce two great novels. Others work more evocatively, like Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), a post-colonial reimagining of Jane Eyre from the point of view of the madwoman in the attic, or Peter Carey’s Jack Maggs (1997), which, with elliptic brilliance, re-situates Magwitch at the heart of the narrative of Great Expectations (1860–61).

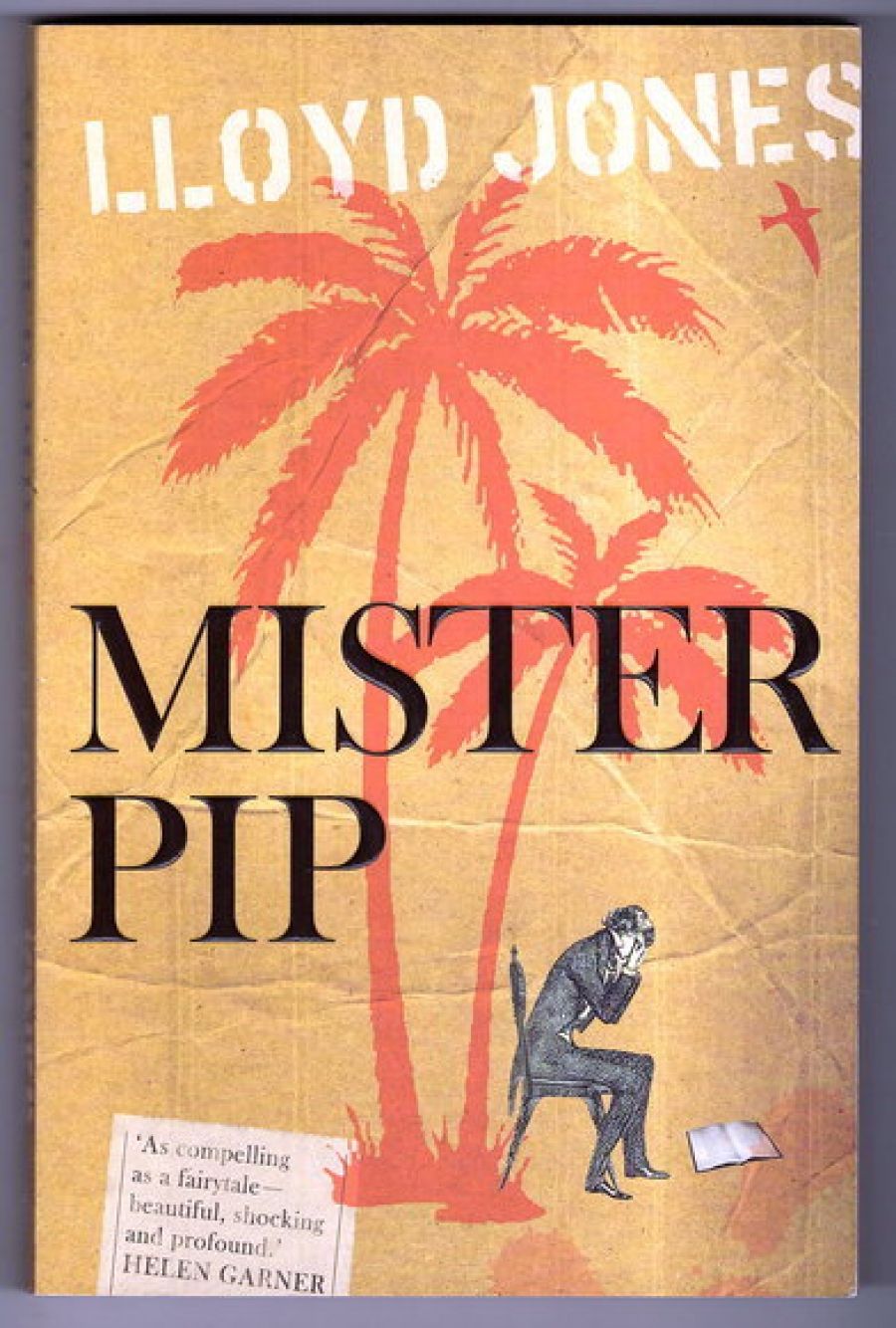

- Book 1 Title: Mister Pip

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $29.95 pb, 220 pp, 1921145579

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Few novels have enjoyed so busy an afterlife as Great Expectations. The multi-medial fascination with this tale of a poor boy who is translated from his constricting world into wider opportunities, for good or ill but certainly for growth, has spawned numerous stage and radio versions, film and television adaptations, an animated version and a ‘graphic novel’ treatment; and no doubt this list is incomplete. There is something powerfully resonant about this Bildungsroman, a fascination that goes beyond, say, ‘wonderful characters’.

It is a fascination that has particular relevance to Australia. Not only have we had Carey’s novel, but also a melodramatic tale simply called Magwitch (1982), by Michael Noonan, and Tim Burstall’s television mini-series, Great Expectations: The Untold Story (1986), both of which focus on convict Magwitch’s life in Australia, relating to the original almost in the manner of a photographic negative to the actual snapshot. Jones’s Mister Pip is much less literally derived from Dickens’s great original, but it wouldn’t exist without this antecedent – and we would have been denied a work of great charm and rigour.

Told, like Great Expectations, in the first person, Mister Pip’s protagonist is a Bougainville Island girl who grows from the age of about ten to young womanhood in the course of the novel. This is essentially her recollection of life in a remote tropical outpost after the copper mine has closed down, after all the white men but one have left, and during the invasion of ‘redskins’ from Port Moresby. Her father has gone to work for the mining company in Queensland, leaving Matilda and her mother to fend for a meagre life on the island.

The only white man left on Bougainville is the unprepossessing Mr Watts, married to black Grace, whom he leads around on a trolley, and his background is as mysterious as hers. To help fill the otherwise empty days of the island children, Mr Watts runs a school, where his main teaching aid is a copy of Great Expectations, which he reads to the children at the rate of a chapter a day. Matilda identifies with Dickens’s Pip, and the parallel is spelt out clearly. ‘I knew that orphaned white kid and that small fragile place he squeezed into between his awful sister and loveable Joe Gargery because the same space came to exist between Mr Watts and my mum. And I knew I would have to choose between the two.’ The choice will eventually be reduced by tragic events.

The island, like Dickens’s forge and Pip, won’t be able to contain her. She, like it, is subjected to buffetings from without and the guerrilla movement within, and, even closer to home, to her mother’s suspicion of the world that Mr Watts’s reading has been opening up to Matilda. When marauders burn Mr Watts’s possessions, including, as he believes, his copy of the great novel, the class tries to retrieve it in fragments of memory, and some of these fragments are less accurate than others. Matilda isn’t the only Pip on the island: Watts, in his own way, has also been Pip, has also once been young and come, in New Zealand, under the influence of an eccentric older woman, the ‘Miss Havisham’ of his life. At one point, too, Matilda fears that ‘somehow he has slipped out of Pip and into Joe Gargery’s skin’. The web of reference to the precursor novel is delicate and unbearably moving. As for the original Pip, it is not Joe or Miss Havisham but Jaggers (a lawyer in Dickens, a fisherman for Matilda) who offers the means of escape to a larger world.

Matilda eventually, after events horrifying enough but treated with austere lack of graphic detail, makes it to Australia, finds her Australianised father, checks out Watts’s New Zealand history, and finally fetches up in England, the England of the British Library, and Gravesend and Rochester. It is not all quite as she has hoped or expected, but what is beautiful to read about is the way she is now able to assess her own experience and to remember how her Mr Dickens had ‘taught every one of us kids that our voice was special… and [to] remember that whatever else happened to us in our lives our voice could never be taken away from us’. She has learnt enough not to follow Pip in the end, but to ‘try to return home’.

Her ‘voice’ is the magical element in this book. Jones is very far from sentimental about this entrancing child’s education. There is a sense of hard truths in her understanding of the limitations of her island and of the disillusionments she meets in London. But there is also a toughly rewarding sense about the nature of fiction’s reality and how its ‘completeness’ squares up to the messy facts of that other reality called life.

Comments powered by CComment