- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Custom Article Title: Sites of Resistance

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sites of Resistance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In her recently published collection of critical writing by indigenous Australians, Michele Grossman notes that ‘[s]ince the early 1980s, the burgeoning interest in and publication of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writing …has become increasingly well-established’. This is particularly true when we consider the success of life-writing by Aboriginal women in the last twenty years. Sally Morgan is practically a household name, and even the once-maligned work of Ruby Langford Ginibi has taken its place on school reading lists around the country.

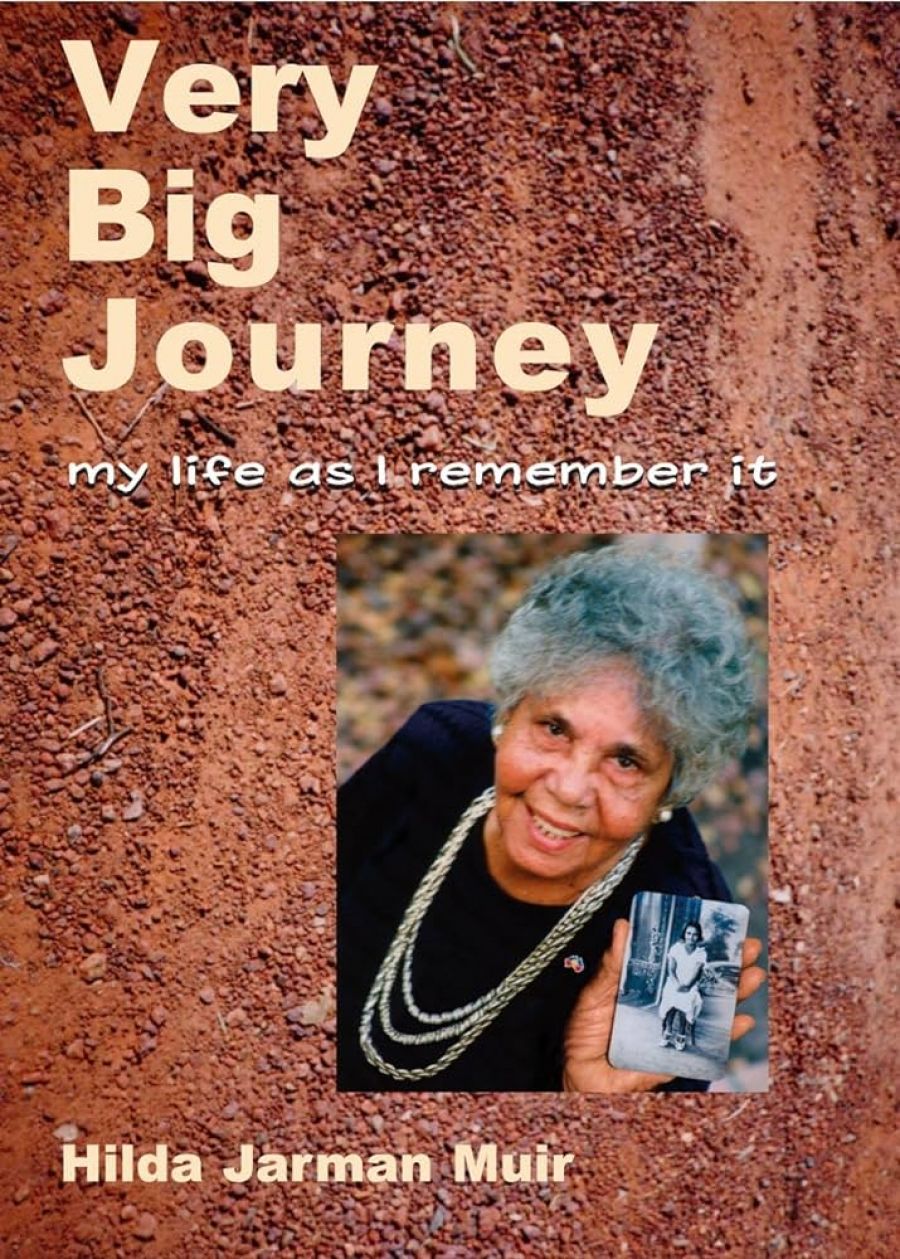

- Book 1 Title: Very Big Journey

- Book 1 Subtitle: My life as I remember it

- Book 1 Biblio: Aboriginal Studies Press, $29.95 pb, 156 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Hilda Jarman Muir’s Very Big Journey is usefully considered in this context. This likeable book reflects a confidence that seems to derive in part from the recent history and success of other Aboriginal women writers. For a start, the 83-year-old author seems to know that this story is an important one, both for her family and for her nation’s history. This confident spirit is encapsulated in the book’s subtitle – ‘my life as I remember it’ – which defies both postmodern theorising about the fictionality of memory and the conservative backlash against what John Howard has called the ‘black armband’ view of history. The subtitle’s message is mirrored in the text when Muir writes: ‘[s]o that’s the end of my story and if people want to say that’s not what happened then good luck to them.’ Though not as cheeky or adventurous as Langford Ginibi, Muir demonstrates a profound determination to be and to represent herself.

This determination seems to have been hard-won. Muir’s description of her childhood in the Kahlin home for ‘half-caste’ children is heart-rending, although the author never displays self-pity. Stating that ‘we were always hungry’, Muir describes the children’s efforts to ‘scavenge’ food – including potato skins, considered a delicacy – from neighbours’ bins. Later, her descriptions of being let loose on the world at the age of fourteen with almost no education, no understanding of contraception and no knowledge of ‘the world outside’ highlight the absurdity of the notion that such homes equipped indigenous children for ‘integration’. World War II and Muir’s experiences of motherhood also seem to have contributed to her strong sense of self. Evacuated from Darwin with the first three of ten children in 1942, Muir arrived in Brisbane a painfully shy young woman. By the time her husband Bill returned from service in New Guinea, however, she resented his recalling the family to Darwin, having established a life and a sense of belonging in the bigger city. For the next decade, she battled with the loneliness and labour associated with living on the outskirts of Darwin and raising ten children. In many ways, her struggles are representative of a broader community of postwar women, who, having gained independence during the war, struggled with its loss when their husbands returned.

Discussing the success of Aboriginal women’s life-writing, academic Anne Brewster proposes that the dominance of this genre by women may reflect Aboriginal women’s assumption of central roles in their homes and communities. Brewster argues that Aboriginal women’s centrality ‘may be due to a change in the structure of Aboriginal society … [including] factors such as the disintegration of traditional family and kinship structures, alcoholism and the high incidence of Aboriginal men in jail’. The fact that Muir’s beloved husband was also something of a drinker and womaniser seems to support this argument.

More positively, Brewster proposes that the dominance of this genre by women can be understood through a notion of the family – ‘a woman-centred arena’ – as a site of resistance. Certainly, Muir’s role as a mother, grand-mother and great-grandmother is of central significance to her story. She writes because she wants ‘the little ones living in Adelaide [to] know that their grandmother was a proud Yanyuwa woman … a saltwater woman’.

The significance of a female-centred indigenous community is also evident in the book’s history. In the foreword to Very Big Journey, ATSIC Regional Chairperson Barbara Cummings writes that ‘the manuscript was assisted by Melissa Lucashenko with the advice and assistance of Jackie Huggins’. Both these indigenous women are successful authors in their own right, the latter of Auntie Rita (1994), itself an innovative collaboration between Huggins and her mother. Challenging the Western world’s sense of authorship as an individualistic affair and achievement, this unabashed depiction of the assistance provided by other Aboriginal women is evidence of how far indigenous writing has come since Colin Johnson’s (Mudrooroo’s) Wild Cat Falling was published in 1965.

Very Big Journey is Hilda Jarman Muir’s story. Nevertheless, a good deal of the book’s joy lies in the author’s hearty self-assertion, and how this seems to have been enabled by a broader indigenous community.

Comments powered by CComment