- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Eating Revelation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

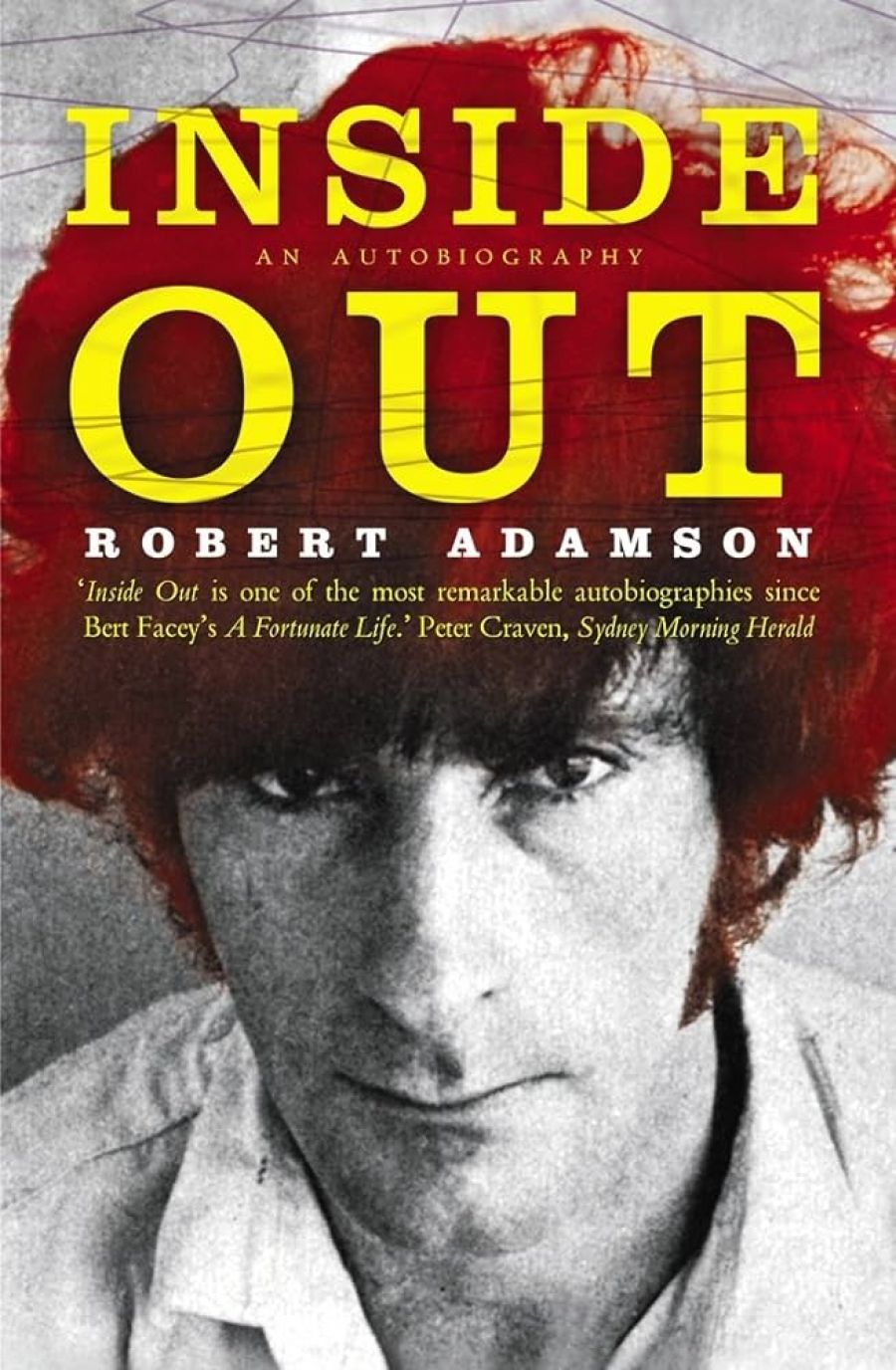

Aptly, John Ashberry has described Robert Adamson as ‘one of Australia’s national treasures’. Since the late 1960s Adamson has been a vital presence in the renaissance of Australian poetry, both in his own work and as an editor and publisher. The immense command of his writing, its trajectory from the early postmodernist explorations of the poet’s voice and the possibilities of Orphic vision to the clear lyricism of his Hawkesbury poems, has made Adamson one of the reasons why Australian poetry, as Clive James often points out, is as good as any being written in English at the present time. And there is an extraordinary story behind the writing, which comes through in the poetry, and which Adamson now relates in Inside Out: An Autobiography.

- Book 1 Title: Inside Out

- Book 1 Subtitle: An autobiography

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $45 hb, 342 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is a strange and wild book, full of grief and fierce in its vision of the redemptive qualities of art and language. Some of the material will be familiar from Adamson’s ‘auto-biographical novella’, Wards of the State (1992), and the autobiographical poems that comprise his collection Where I Come From (1979).

Robert Adamson was born in 1943, the son of a roughrider in rodeos who had become a bottle collector. He tells us that ‘my mother’s family were harbour people, my maternal grandmother a Scot, married to a carpenter. My father’s family were river folk, my paternal grandmother Irish, her husband a lamplighter and fisherman.’ His schooling was unhappy; he wanted to be an ornithologist, but he was dyslexic and bad at maths, and grew bored. Dinner at the Adamsons’ was not fun: his father was often drunk, and his mother given to dour homilies about morality: ‘she always did the right thing and always expected the worst.’ Once, when Robert attempted to defend his mother from his father’s insults, she turned on him and made him feel as if he was in the wrong. His first encounter with the law came when he stole a rare bird, a Ptilorus magnificus, or riflebird, from the Tooronga Park Zoo. When he broke his good behaviour bond the following year by stealing a Gestetner machine from his school, he was sent to Mount Penang Training School for Boys.

On his release, he found work as an apprentice pastry cook and flourished under the perfectionistic demands of his boss. Again, naughtiness got the better of him. He smashed the stolen car he was driving with a girlfriend; when he regained consciousness, he learned that she was crippled for life. Following his release from his second stint in Mount Penang, he met up with Carol: ‘with her black hair and pissed-off eyes. She caught me in the corner of one of them: eyes of spite that gave you a glimpse of panic and hurt, as if something inside had been twisted. I loved her the moment I saw her.’ Carol was not a good girl; Adamson’s mother was not leased. In another stolen car, they tried to elope to Queensland, and when the cops caught up with them on the border, it turned out that Carol was only fifteen. This time it was Long Bay for Adamson, and a lower circle of violence and degradation.

It is not easy to read this book without having to suppress a Pharisaical reaction to it: Adamson behaved badly in his youth, repeatedly; and although you see the relationship between the moralising he had to suffer at the hands of his mother and grandmother and the negative self-assertion of criminality, you feel a certain impatience with his impulsiveness.

In a book full of memorable images – Adamson as a boy climbing up the drainpipes of blocks of flats to steal birds from the eaves, two boys sitting in the rain, masturbating each other under their coats – one scene stands out. Adamson is in solitary confinement, in the dark, at Long Bay and requests a copy of the Bible. He had heard that, even though it was too dark to read, just having the pages to riffle makes the experience less alienating:

I wondered about the thin band of radiance at the bottom of the door, then crawled towards it: a slit of feeble yellow light that cast no light beyond itself. I opened the Bible at a random page and tried to angle it up close to this slit, but no light fell on it. I couldn’t make out a single word. Then I had an idea. If I ripped out a page, I could poke it into the gap between the door and the floor. I hesitated, realising that if the screws caught me, I’d be up on another charge.

There is enough light to read Revelation one line at a time. When Adamson is finished, he eats the page. It is one of those images of extremity and ingenuity that perhaps can only occur in prison literature, and it stays in one’s head for days.

During his last prison sentence, in Long Bay, Adamson was raped. To protect himself from further attacks, he convinced the governor that he was gay, or at least bisexual, and so was placed in a cell alone. Adamson’s description of the assault is graphic and unmelodramatic, and makes you marvel at his resilience. To have come through these accumulated horrors with his gifts intact shows an enviable strength of mind and, ultimately, a sense of purpose beneath the waywardness. It is as if literature was waiting to descend on him, redeeming the waste and pain. It was during this period that Adamson began to write poetry.

Listening to Bob Dylan on the radio inspired him to try his hand at songwriting. The prison chaplain, shown some of his lyrics, told him that he was writing poetry, and gave him Gerald Manley Hopkins to read. A friend in prison spoke of Rimbaud, but it was only when he left gaol that he read the poet who, with Shelley and Dylan, had the greatest effect on his emerging literary consciousness (his girlfriend Denise having checked with his mentors, the painter David Rankin and his wife, that he was ‘ready’ for Rimbaud, that he could ‘handle it’). Adamson’s first published poem, ‘Jerusalem Bay’, dates from this time: ‘I walked through a solitude of mist, by a river / reflecting a spiral of stars; at the top spun Mars as tense as my fist / Then down the valley shaped of crosses, with the stab of my eyes on the tide / ebbed still, as crab-etched mud fell into craters where nippers skated. / Shadows slid over the bay, dull thuds of fishermen working, flounced on my /blood then.’

The last hundred pages of the book, about Adamson’s emergence into the poetry scene of Sydney in the late 1960s, are almost necessarily less compelling: the wars between Poetry Australia and Poetry Magazine, and the Balmain escapades of Frank Moorhouse, Michael Dransfield and co., seem mundane compared to what preceded them. But you are moved, all the same, by the spectacle of Adamson rescuing himself from the catastrophes of his earlier life.

Comments powered by CComment