- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: True Crime

- Custom Article Title: Juanita’s Fate

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Juanita’s Fate

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

So who did murder Juanita Nielsen? Years of corrupt police inquiries and coronial and parliamentary investigations have failed to identify her killers, but this excellent history of Sydney’s most famous unsolved disappearance provides most of the answers. However, while it may fill many of the gaps in the record, the question of justice for Juanita is quite another matter. A number of key identities, such as Jim Anderson and Frank Theeman, are now dead. Others have had their testimony tainted by a lifetime of drug addiction and turmoil. Like the ultimate fate of Victoria Street, Kings Cross, the battle for which ultimately cost Nielsen her life, there is no neat ending to this story.

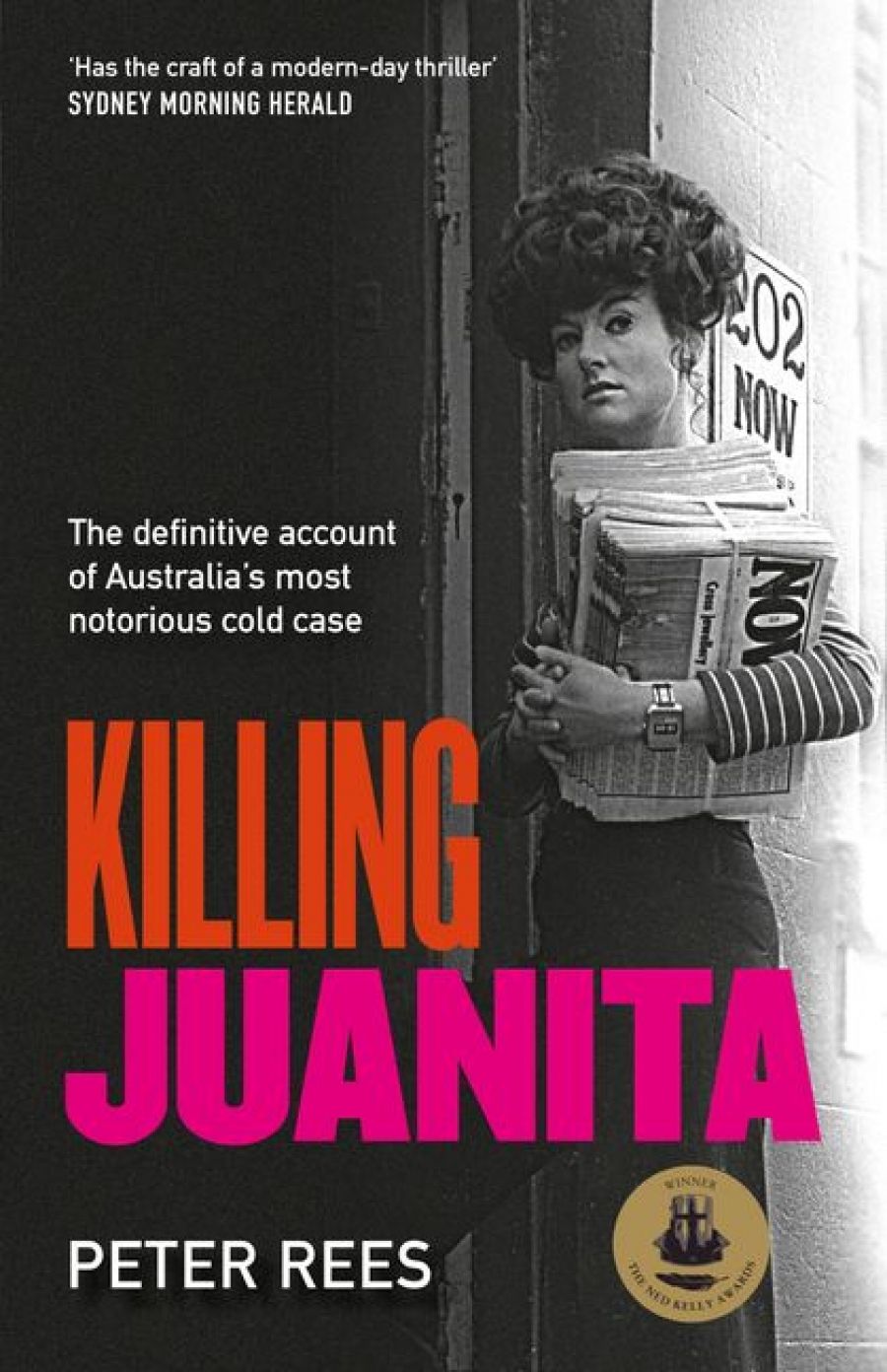

- Book 1 Title: Killing Juanita

- Book 1 Subtitle: A True Story of Murder and Corruption

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 275 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Over the years, there have been all manner of weird theories about the murder, but Peter Rees brings the story back to where it started and establishes, in my view, a conclusive case for his conclusion:

Juanita was not killed because of fictitious dossiers or tapes or, as Jim Anderson would have people believe, because she stumbled over information linking the Nugan Hand Bank to drugs in Griffith and was shot by Fred Krahe. Rather she died for one reason only – her strident and effective opposition to the redevelopment of Victoria Street.

The book does not answer the question of exactly how Juanita was killed or where her body may lie. It seems most likely that she was killed at the Carousel nightclub on the morning of 4 July 1975. She may have been shot in a storeroom there. Her body was subsequently disposed of and has never been found. Responsibility for the killing rests with a Kings Cross club owner and stand-over man, Jim Anderson, despite the fact that he denied responsibility on his deathbed. These are the bare bones of the mystery.

What we do know is that around 10 a.m. on that showery and overcast winter’s morning, Juanita Nielsen, a wealthy Sydney heiress, publisher and anti-development campaigner, walked up Earl Place in Kings Cross to the Carousel nightclub on the corner of Darlinghurst Road and Roslyn Street to keep an appointment. She entered the club, had a negotiation about the sale of advertising space in the local newspaper with an associate of Anderson’s named Eddie Trigg. She was never seen again.

Three days later, a road maintenance gang working on the F4 freeway, the main route through Sydney’s west, found a black leather handbag on the side of the eastbound lane, about a kilometre from the junction with the Great Western Highway. Later, a schoolboy produced cosmetics and other personal effects found by the side of the road. The handbag and its contents had clearly been thrown from a moving car heading back to Sydney from the Blue Mountains. Although identified as Juanita’s, the evidence was frustratingly free of clues that could take the investigation further. The initial police inquiries were ineffective and tainted by corruption.

Juanita Nielsen was an heir to the Mark Foys retail empire in Sydney. Born Juanita Joan Smith in 1937, she was the only child of Neil and Wilma Smith, a wealthy branch of the

Mary Foys family. As Rees says, it was a privileged background. They were super rich, the Great Gatsbys of the city, even wealthier than the Fairfaxes.

Early on, Juanita revealed an adventurous spirit that wasn’t going to see her tied down to the predictable life of Eastern Suburbs party girl. Aged twenty-two, she went to Europe and adventure. She married a Norwegian seaman, Jorgen Nielsen, much to the dismay of her parents. The marriage eventually broke up. Back in Sydney, Juanita got involved with a bitter dispute with her family over a takeover offer for the family business. Juanita had worked in the business and opposed the takeover, adamant that it was undervaluing her birthright. Although she was proved right, the dispute caused a bitter rift with her father, who had agreed to sell. The schism was later healed, partly as a result of a gift of money, which Juanita reluctantly accepted.

With the funds, she bought a house in Victoria Street and acquired a local newspaper called NOW, which ran advertorials on local businesses. Juanita loved the process of selling the ads and getting the paper out. Increasingly, she used it as a platform for her views, including bitter opposition to the redevelopment of Victoria Street by the developer Frank Theeman.

Theeman had made his pile in the women’s underwear business and had big plans for Victoria Street. He wanted high-rise towers and the destruction of the old and graceful terraces. He systematically bought up properties, hired thugs to abuse and intimidate tenants into leaving, and vandalised properties to make them uninhabitable. His tactics led to the imposition of green bans by the Builders Labourers’ Federation, led by Jack Mundey (briefly Nielsen’s lover), and opposition from planning authorities and the National Trust.

It was the early 1970s, a pivotal time in the life of Sydney, when much of the Rocks and Woolloomooloo could have been lost to the developers. Theeman was losing money. He came to see Nielsen and her campaign against him as one of the main obstacles to his grandiose vision. The one thing that always seemed to work was force: he contacted Jim Anderson and paid him $25,000. Anderson was a thug who controlled clubs and much of what went on in the Cross.

On his deathbed, Theeman was asked if there was anything he wanted to confess about the Nielsen case to clear his conscience. He shook his head. ‘I could not do it because of my family. I am dying and I want to die in peace.’ As Abe Saffron says in the book: ‘That sums it up.’

Like any good biography, Killing Juanita is the story of its time as well as of the main protagonist. The book provides a compelling picture of what inner-city Sydney was like around the Cross and Woolloomooloo. The cops and politicians were corrupt; developers and powerful men regularly employed thugs and criminals to further their ends. Criminals such as Jim Anderson were left unpunished.

And in the end, was Victoria Street saved? Not really. Theeman’s aspirations were ultimately realised in another way, with a low-rise development that stepped back and down Victoria Street’s western escarpment. That’s one of the many ironies of the tale of Juanita Nielsen. Another is that the old Mark Foys emporium is now refurbished and called the Downing Centre. It’s Sydney’s biggest local court complex.

I suspect Juanita would have liked that one.

Comments powered by CComment