- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: YA Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Other Worlds

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For a reviewer, there’s always a temptation to seek a link when writing about more than one book at a time. In this instance, the link, if there is one, is that both these novels for young adults attempt to recreate other worlds, albeit in one case an imagined one, in the other a ‘real’ one. In other respects, however, they could hardly be more different. One credits its readers with intelligence and stamina, the other condescends to them.

- Book 1 Title: The View from Ararat

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP $14.90 pb, 268 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

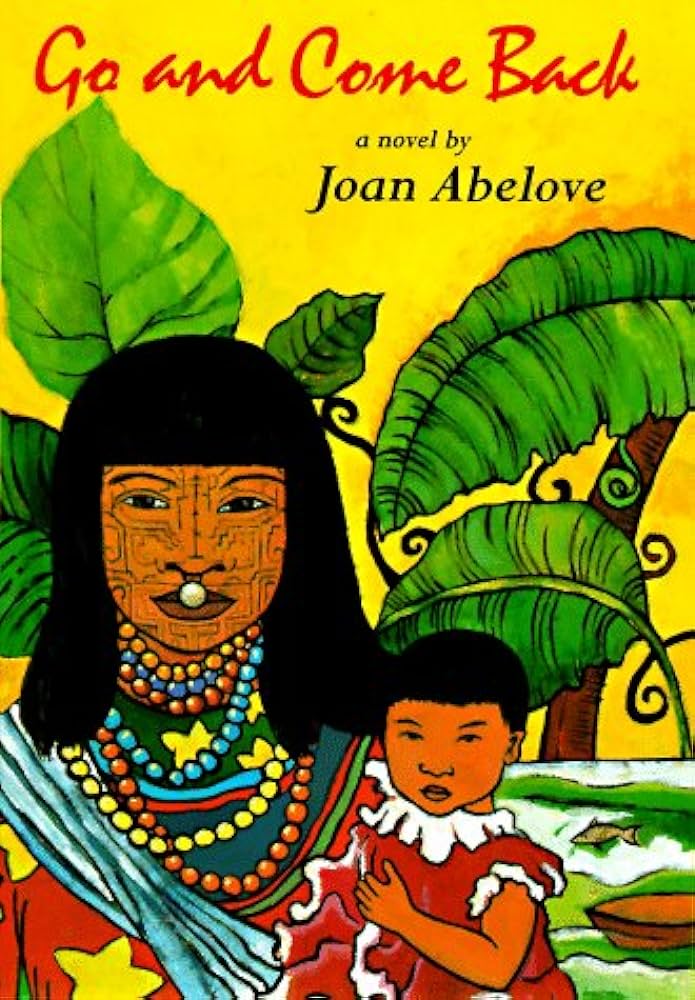

- Book 2 Title: Go and Come Back

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $14.90 pb, 177 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The View from Ararat is another of the complex futuristic multi-voiced narratives in which Brian Caswell has come to specialise and which, in style and scope, bring to mind the work of John Brunner. The story takes place on the planet of Deucalion, familiar to readers of Caswell’s earlier novel of the same name. In The View from Ararat, set some years later, Deucalion is threatened by a plague-like, invariably fatal, disease unwittingly imported from Earth. While researchers rush to find the origin of the disease, and a cure for it, the planet’s politicians apply every means at their disposal to contain the spread of the disease. Given the urgency of the crisis, it’s the more ruthless and violent measures which offer most appeal.

Caswell’s prose, as usual, is admirably clear and fluent. In this case, however, that isn’t enough to overcome the fragmentary structure. The multivocal technique – which, when it works, provides exhilarating exercise for readers’ minds – is stretched here surely to its utmost limits: in the first 40 pages, 10 points of view are used. The complexity deepens as the novel goes on: there are not only different points of view but also different means of conveying them, some characters’ stories being told alternately in first and third person segments. Because of the multiple voices, and the associated time shifts, it’s very difficult at first to hold on to the thread Caswell is weaving.

Eventually it does become easier to follow what’s happening and, as the plague crisis spreads through Deucalion some tension is developed. However, it remains difficult throughout the book to develop any real empathy with the characters and their predicament. This tends to work against Caswell’s presumed intention to encourage thought and discussion about a clutch of intractable moral, social and political dilemmas. The dilemmas are obscured, diminished even, by the over intricate technique. It’s as if Caswell had less interest in exploring the issues than in experimenting with a form of expression which clearly fascinates him.

I’m to acknowledge that the cause of the books difficulty for me may be the number of years separating me from the experience of today’s young readers, trained by a lifetimes of acquaintance with television’s fractured, lightning-fast narratives. And at least The View from Ararat makes demands on its readers, young or old.

Go and Come Back, on the other hand, merely patronises them. Ostensibly based on the experiences of its author, a cultural anthropologist, who lived for two years in a village in Peru, in the Amazonian forest, the book tells how the villagers react to the arrival of ‘two old white ladies’ – in fact two American anthropologists in their late twenties. One of the villagers, teenaged Alicia, is the narrator.

There is, undoubtedly, much virtue in seeing our culture through the eyes of outsiders, just as it can be very enlightening and worthwhile to be exposed to the beliefs and practices of another culture. However, there are risks in using an essentially naive narrator to tell a story such as this, especially when, like Abelove, you’re a novice as a novelist. The technique constrains not only what we can learn about Alicia’s culture but also what we can be shown of our own. Here, we tend to be shown only the positive aspects of Alicia’s life and only a negative perception of Western culture – or at least of how it’s represented by two not necessarily typical American women.

Over and over again we’re presented with Alicia’s startled reaction to the difference between Western customs, attitudes and expectations and her own. Essentially, it’s that single idea, albeit with variations, on which the novel’s foundations rest. It’s not enough. I wanted to know more about Alicia’s way of life-things that she couldn’t perceive, things that she might have chosen to overlook. Given, moreover, that there’s so little trace of literary flair to enliven the whole thing, it’s hard to imagine modern teenagers reading the book with any enthusiasm, unless the central idea is new to them, which is hard to imagine in these days of multiculturalism. New idea or not, however, any thoughtful reader is more than likely to be put off by the relentless worthiness of Abelove’s apparent intentions. Her experiences would, I suspect, have been better rendered in non-fictional form.

Comments powered by CComment