- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Storm in a Tea Cup

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The publication of this book has created somewhat of a storm in a teacup. Melbourne researcher, Maja Sainisch-Plimer, demanded its recall, claiming the book misrepresented the findings of her research over the twenty years. The publisher, Graeme Ryan, placed a Notice to Bookshops in the book pages of The Age claiming unfair practice and advising bookshops ‘to confidently display and sell Anya: Countess of Adelaide’. Subsequently the book has been reclassified by the National Library from biography to fiction.

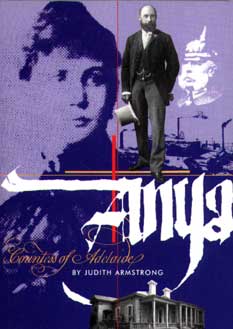

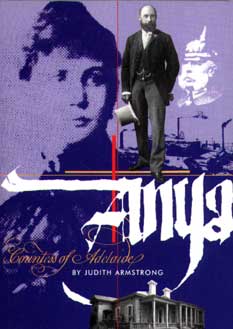

- Book 1 Title: Anya

- Book 1 Subtitle: Countess of Adelaide

- Book 1 Biblio: Ryan Publishing, $19.95 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The early part of the book, a fairly predictable tale of an ambitious young woman coming to a new country with little more than her virtue, holds the reader. But later, Judith Armstrong, whose biography of Clem and Nina Christesen was shortlisted for the Age Book of the Year award, struggles with the tale of this supremely dull and socially pretentious woman. Once Anya is safely married to Charles Rasp (who turns out to be the son of noble family, really one Hieronymus Salvator Lopez von Pereira), nothing much happens, except they furnish and decorate a mansion together in the solid Suburb of Medindie, complete with lead-light windows depicting the heroes of the Franco-Prussian War, none other than von Rohn, von Stosch, von Motlke, von Bismarck, and Emperor Wilhelm himself. ‘Charles would sit in the great lead-light hall for hours on end, a book of German history on his knee, his eyes faraway’, thinking of Frieda, his long-lost love, and seemingly avoiding intercourse of any sort with his wife. Until one day he dies and his widow sets out for Europe to buy herself a suitable husband and renewed social status. The controversy over the book’s release raises the question of the rules concerning ‘factional’ biography, whether an author can take the bare bones of a real life and flesh it out with invention. The answer to this must surely be that a writer can do anything he or she likes if the work is good enough. Where subject matter is unworthy and style allows potential lovers’ eyes to ‘flash’ in consecutive paragraphs, simple errors and inconsistencies become unduly noticeable and irritating. Armstrong’s tenuous grasp of South Australian geography leads her into strange errors such as relocating Port Adelaide on a bay rather than the Port River and twenty-five miles from the city rather than its actual seven or eight. She even reiterates this last fact in a literary device just to make sure the error does not escape unnoticed. In 1885, she has her newly married couple enjoying a clear view from the South Australian Hotel down to the Torrens which surely must have been impeded by the railway station and Parliament House in their finished forms or in some state of construction. Charles Rasp’s friend and lawyer, James Henderson, could not have organised the unlikely event of a wedding party at the even more unlikely Adelaide Club with its splendid receptions rooms, with their thick carpets and crystal chandeliers’ as, contrary to Armstrong’s statement, Henderson was not a member until 1903. Nor does it seem possible that another real person, Professor Archibald Watson, was ‘charging’ about Adelaide on a motorbike in what seems to be the late l 880s, a decade or so before that was a possibility unless he invented and built his own machine. Archie Watson never liked Anya and, rather than go to his friend Rasp’s wedding, chose to attend a ball at Torrens Park. I doubt whether his hosts, that intelligent couple so wonderfully documented in Joanna and Robert: the Barr Smiths’ life in letters, 1853–1919 (ed. Fayette Gosse), would have had much time for Mrs Charles Rasp under any guise.

Even the author, by the time of Anya’s multiple wedding plans to minor European aristocrats at the end of the book, regards her with little more than contempt – as must the reader. And though Anya’s eventual marriage to Count von Zedwitz certainly entitled her to call herself Countess, the Countess of Adelaide part of the book’s title I presume must be ironic. If not, it’s just plain silly.

Comments powered by CComment