- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a drum I’ve been beating for some time, but it’s worth thumping it again here: now is a good time, if you want vigorous intellectual debate, to eschew highbrow literature and dive into popular fiction.

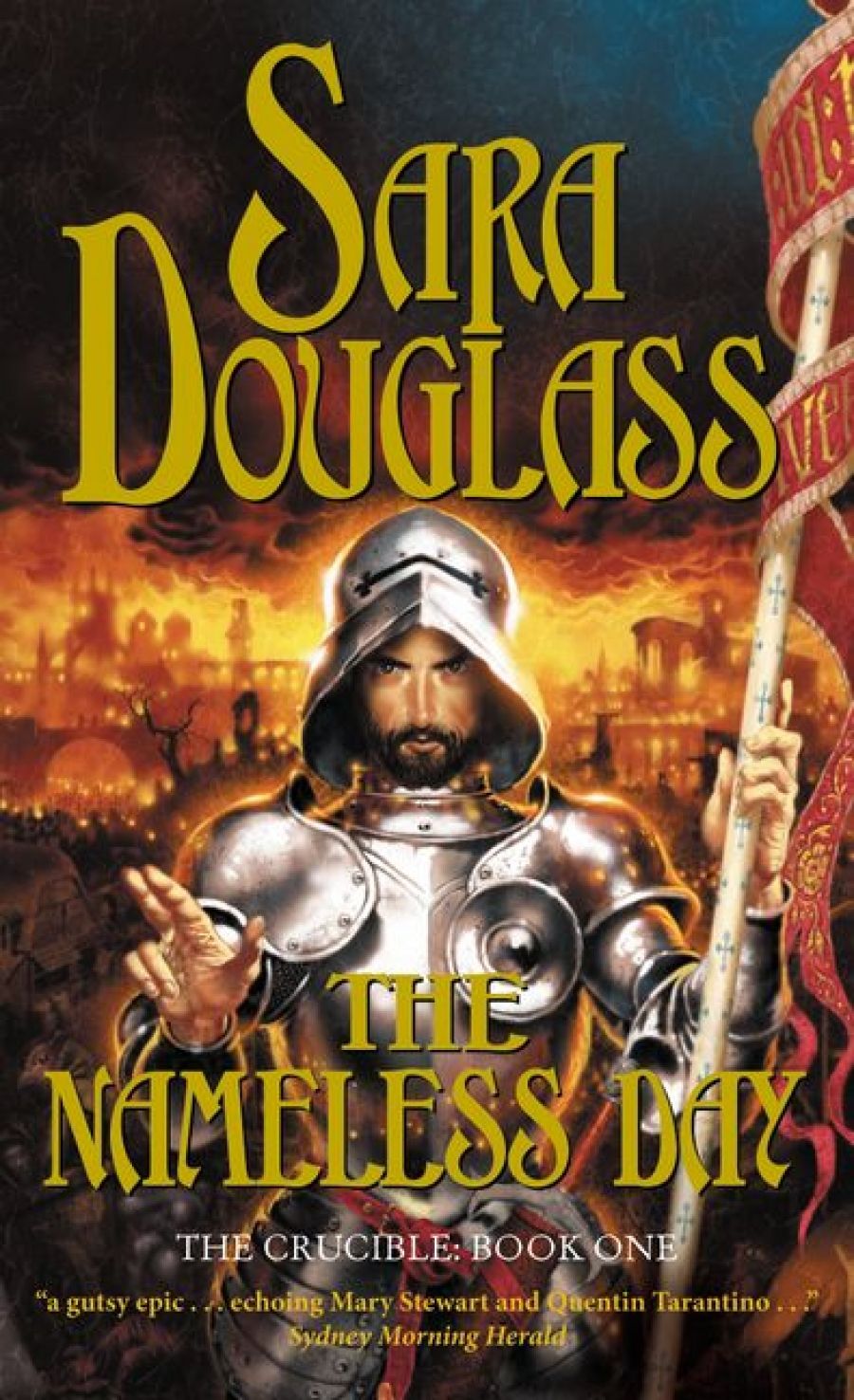

- Book 1 Title: The Nameless Day

- Book 1 Biblio: Voyager (HarperCollins), $36.95 hb, 584 pp

Take the fourteenth century, for example, where so much strange and bad stuff happened that we are still reeling from the consequences six centuries later: the great famine of 1315-20, the Plague, the Hundred Years War, the divided papacy (two popes, one in Avignon, the other in Rome), the suppression of the Peasants’ revolt in England and proto-democratic movements elsewhere, and much more. In my day you could find out a bit about all this, not enough, at Melbourne University Library.

Now all you need to read is popular fiction, preferably written by young Australian women known primarily as authors for teenagers. There’s Catherine Jinks for example, with The Inquisitor (1999) and The Notary (2000). And now there’s Sara Douglass with The Nameless Day. Read books like these and you’ll feel as if your brain has just been through a dishwasher.

Do any of you find it odd, even rather shameful, that an intellectual ferment is taking place in books regarded by much of the press – in the case of Douglass – as unfit for review, presumably on the principle that best-sellers are beneath contempt?

The Nameless Day is Book One of a trilogy entitled The Crucible. The protagonist is Thomas Neville, once a lord from a noble family in the north of England, now a Dominican Friar. Thomas’s task, he is told by the Archangel Michael who periodically appears to him, is to replace the now dead Wynkyn de Worde as the one man who can keep closed a gateway to Hell near Nuremburg called the Cleft, through which shape-changing demons can come to populate our world. Most of the few in whom Thomas confides his task believe him to be deranged.

So this is a parallel fourteenth century. The degree to which powers of good and evil can supernaturally manifest themselves in our own world is moot. But in the parallel world that Sara Douglass creates the supernatural is real. It’s not a bad way to dramatise moral conflict, though it could prove a touch too lurid for some readers. (It is parallel in another way too. Small changes have been made to the historical facts of our own world, in order to compress events around a narrative cusp, so that for example Richard II is eighteen rather than nine when he ascends to the throne.)

Sara Douglass’s real daring is in doing what is generally supposed to be a very dangerous thing in popular fiction, many of whose readers are notoriously deaf to irony. She creates a point-of-view character whose views may indeed be diametrically opposed to the author’s own. The views espoused by Thomas and the Archangel Michael are appallingly conservative for us, and even by fourteenth century standards they’re pretty rigid. The world is hierarchical, with peasants and labourers at the bottom. To disturb the hierarchy is to commit heresy as well as treason. Thus the proto-democratic Lollard preacher John Ball is regarded by Thomas as literally evil incarnate. It was Ball who wrote the touching words (not quoted by Douglass), ‘And do well and better, and fleeeth sin, / And seeketh peace, and hold you therein.’ Women are the sinful instigators of male lust, and in that respect at least are to be despised. The Cleft in The Nameless Day is overtly compared to a vagina, moist and dangerous, which may be interpreted as suggesting that to Thomas and Wynkyn, sexual appetite is the work of demons.

Some readers may not believe things were ever as bad as Douglass claims, but it is not difficult to find supporting evidence. A Latin tag much quoted by fourteenth century philosophers was ‘omnis ardentior amator propriae uxoris adulter est’, which may be translated as ‘to love one’s wife with physical passion is to commit adultery’. But here I would like to register a dissenting voice. Doesn’t Douglass give only one side of the complex view of womanhood at that time? For the fourteenth century was also when the idea of courtly love – which involves the near heretical veneration of womanhood, or a particular adored woman, as a vessel of spiritual ascendancy – was paramount in courtly circles, though the notion never reached the great mass of the labouring classes. Thus this is a century in which – as arguably our own remains for some men – it was possible to believe that women are receptacles of sin and grace simultaneously.

Jinks writes a little more elegantly than Douglass, but Douglass may be more robust. Her inventiveness, her willingness to take narrative risks, her unflinching refusal to be anything other than full-blooded, is admirable. This is a rip-roaring read, whizzing through the politics of the two Popes, the Black Prince’s French campaigns, the sudden death of Edward III and a variety of scary supernatural events including an eerie childbirth, like some juggernaut of plot. One can excuse the occasional crudity of expression, because there is eloquence as well.

Has she been too brave? The anti-Christian philosophy that has been implicit in much of her work, all of which is structured round dramatisations of moral debate – especially the Axis fantasy trilogy – is here explicit. Douglass believes the legacy of the fourteenth century has been a disastrous one for us all, and I suspect she blames Christianity, seen by her as a cruel, paternalist religion, anti-life, anti-woman, and anti-freedom. In short, though much is yet to happen and Sara Douglass plays some cards close to her chest, the thrust of Book One is fairly clearly that she is coming down on the side of the Devil, whom she certainly gives the best tunes. Thus we have the intriguing prospect of a popular work of Satanism being possibly sold in America (I’m sure Douglass hopes it will be and so do I), home of the conservative, fundamentalist right, where even Harry Potter is regarded as an agent of evil.

Comments powered by CComment