- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

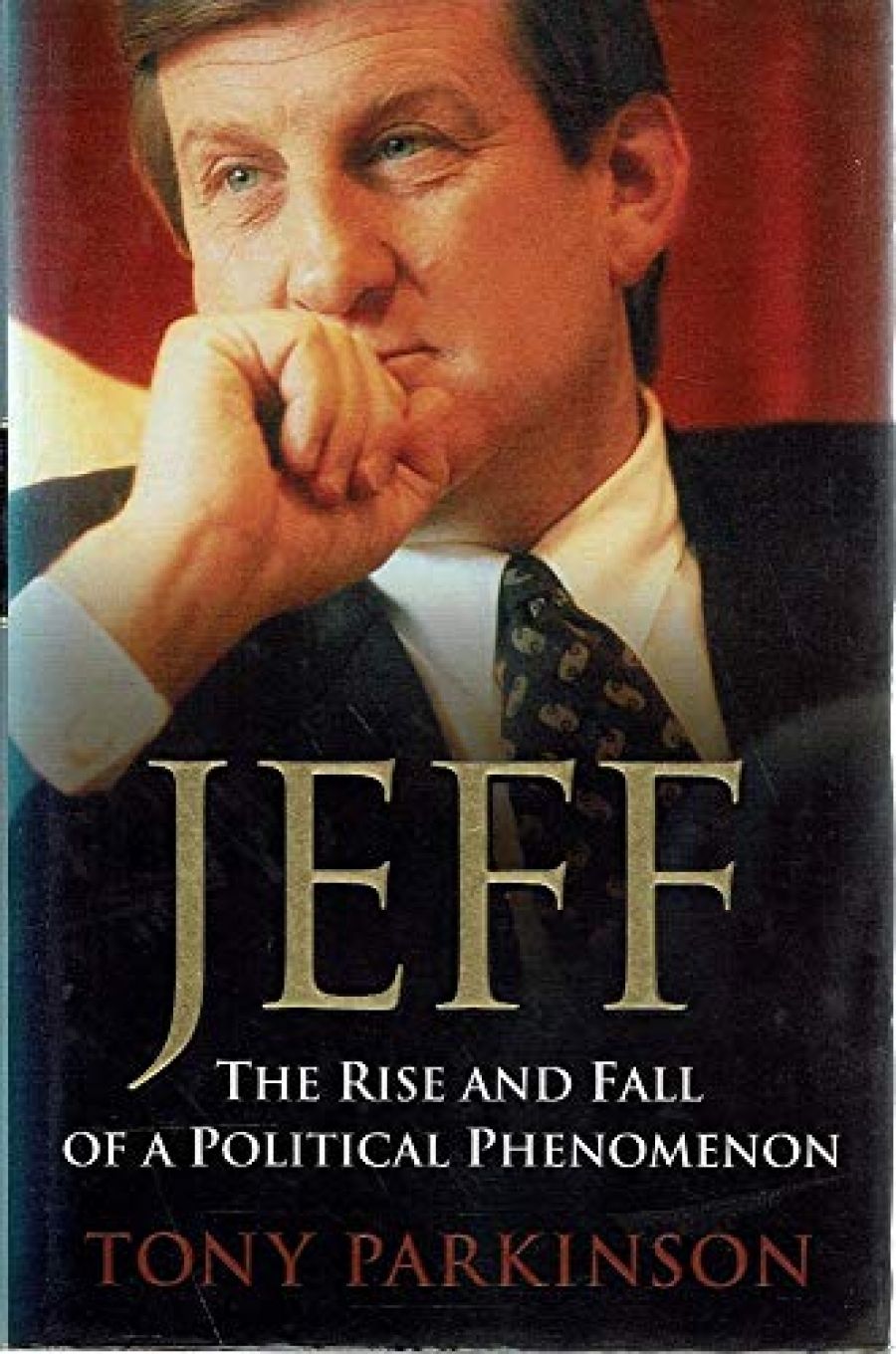

Political biographies are renowned as being notoriously difficult to write. Given the peculiar role of authorisation this is not surprising. The ‘authorisation’ – the act of writing – of a political biography is diminished and crowded out by a subject who not only defines the work’s content, but can literally refuse to authorise the text. In this context, Tony Parkinson’s biography of Jeff Kennett, Jeff: The rise and fall of a political phenomenon, runs up against a subject who is particularly adept at controlling the manufacture of his personal and public self. Parkinson’s biography is unauthorised, but has survived its subject’s scrutiny.

- Book 1 Title: Jeff

- Book 1 Subtitle: The rise and fall of a political phenomenon

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $45 hb, 471 pp

It can be seen in the context of two contrasting, somewhat phantom biographies of Kennett. Firstly, an unauthorised biography which was literally killed when Kennett made it clear that nobody would talk to the particular journalist. The other was of course the biography authorised in the strongest possible sense by Kennett, who commissioned historian Malcolm Kennedy to the tune of $100,000 of taxpayers’ money, along with a hand-picked editorial team, to write an account of the Kennett legacy. In the middle of these extremes, Parkinson’s account of Kennett appears as a diligent chronicle, chunky, comprehensive in its delineation of the Kennett era, but hampered by an absence of critical analysis. As a foot-solider of the present ALP government, my own views on the book’s lack of critical bite are not, it must be said at the outset, wholly disinterested, but Kennett singularly fails to leave anyone disinterested.

Parkinson’s timing was impeccable, with Kennett’s recent dramatic fall calling out for assessment, for an acute analysis of Kennett’s personal and public legacy. That it doesn’t achieve this is partly a fact of the genre: that political biographies often don’t work much deeper than the conventional portraits their covers invariably display. It’s also a fact of Parkinson’s position as an Age journalist. While long, the book is a relatively quick read, slipping into a journalistic gear rather than working over tougher critical terrain. Despite its unavoidable emphasis on Kennett’s political personality, it doesn’t acutely analyse Kennett’s psychological construction in the public realm.

Parkinson is good on Kennett’s relationship with the media, revealing a leader highly aware of his discursive power. Those who were antagonistic, like Age editor Bruce Guthrie, or The 7.30 Report, were ignored. As a fundamentally anti-theoretical personality, hostile to abstraction, Kennett preferred the direct and anecdotal medium of radio and 3AW, where he could fashion his worldview and personal whims into rhetorical effect. Parkinson describes Kennett as a leader who ‘burst free of the carefully constructed corsetry of political dialogue’. Kennett’s attraction for Parkinson is that he breaks out of the practice political limitations that in turn constrains his own journalistic practice – his ability to provide competitive copy. This is an important attraction given Kennett’s hostility towards The Age and the difficulty of drawing stories from an uncooperative leader. However, this is an attraction to rhetorical style above all, and draws the book into Kennett’s slipstream. Rather than digging into its subject, the book is propelled by it, and like the man of perpetual motion himself, runs constantly onwards.

But Parkinson’s account is a valuable chronicle, if not analysis, of Kennett’s effect on Victoria. His research into Kennett’s restructuring of the bureaucracy provides an eye-opening insight into the mechanics of government. It shows the wholesale dismantling of bureaucratic structures, the ruthless efficiency with which Kennett cut departmental funding, streamlined management, and installed a top-driven corporate culture of punishment and reward. It shows him walking unannounced into meetings with startled office staff, and booting departmental heads out of their offices.

In his enthusiasm for Kennett’s obsession with competitive efficiency and sheer momentum however, Parkinson skates over its damaging impact on processes of democratic openness, accountability and independence. The keys to Kennett’s fall are missed here, with Kennett’s 1997 changes to the Auditor General’s role and to common law rights depicted within a continuum of reform, rather than as symbolic moments coalescing around issues of accountability and justice. The rejection by rural and regional voters in the 1999 election is then seen as somewhat unpredictable, rather than as the product of practical and symbolic resentment over citizens’ unequal positions before the Government.

Parkinson downplays the massive importance of sheer contingency in Kennett’s rule. In an era of Parliamentary horse-trading between Upper and Lower Houses throughout Australia, Kennett’s total dominance of both Houses of Parliament was absolutely pivotal to his success. It was the key enabling him to give full reign to his exceptional and ruthless managerial skills. It also partially explains how Kennett managed to drive an entirely ideological agenda of economic reform, while revealing no founding ideological background. Parkinson’s account of Kennett’s military background is fascinating in the context of his management of government. The rigours of military training make for a perfect background for his role as transformer of government into a corporate model, driven by a strong leader, with an authoritative chain of command and dedicated to a singular (if not common) goal.

The sense of a comprehensive description, which nonetheless misses the contextual keys to Kennett’s personal and political trajectory, is highlighted in Parkinson’s summation of Kennett as ultimately ineffable. Kennett is described sniffing the electoral wind in May 1999, and deciding not to spend some of the enormous budget surplus on an electorate suffering reform fatigue. Why does he stick to his guns, stubbornly refusing to divert from the stringency of the past seven years? In the end, Parkinson paraphrases Kennett’s staff, ‘It’s just Jeff being Jeff’. Kennett is seen as an unexplainable entity. ‘Jeff’ as an omnipresent brand, in your face but ultimately superficial and unknowable. It also plays into the hands of Kennett’s genius for constructing the monologue of a political personality.

Kennett here appears, as he did on Neil Mitchell so often, as a father of the state, a tad over-familiar, in a gruff and scolding, but also idiosyncratic way. But that overfamiliarity tips quickly over into a corresponding rejection of the strong leader. It is also the rule of the market, where overexposure and obsolescence are built into the very notion of remorseless progress driven so effectively by Kennett.

Comments powered by CComment