- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In last year’s Cat Catcher, Caroline Shaw established her detective heroine, Lenny Aaron, as one of the most original characters in recent Australian crime (Cat Catcher was runner-up for the Australian Crime Writers Association Ned Kelly Award for best first novel). Gaunt, weird looking, an obsessive compulsive with a phobia about being touched and a serious addiction to over-the-counter drug cocktails, Lennie is in the tradition of dysfunctional and damaged investigators muddling their way through recent crime fiction.

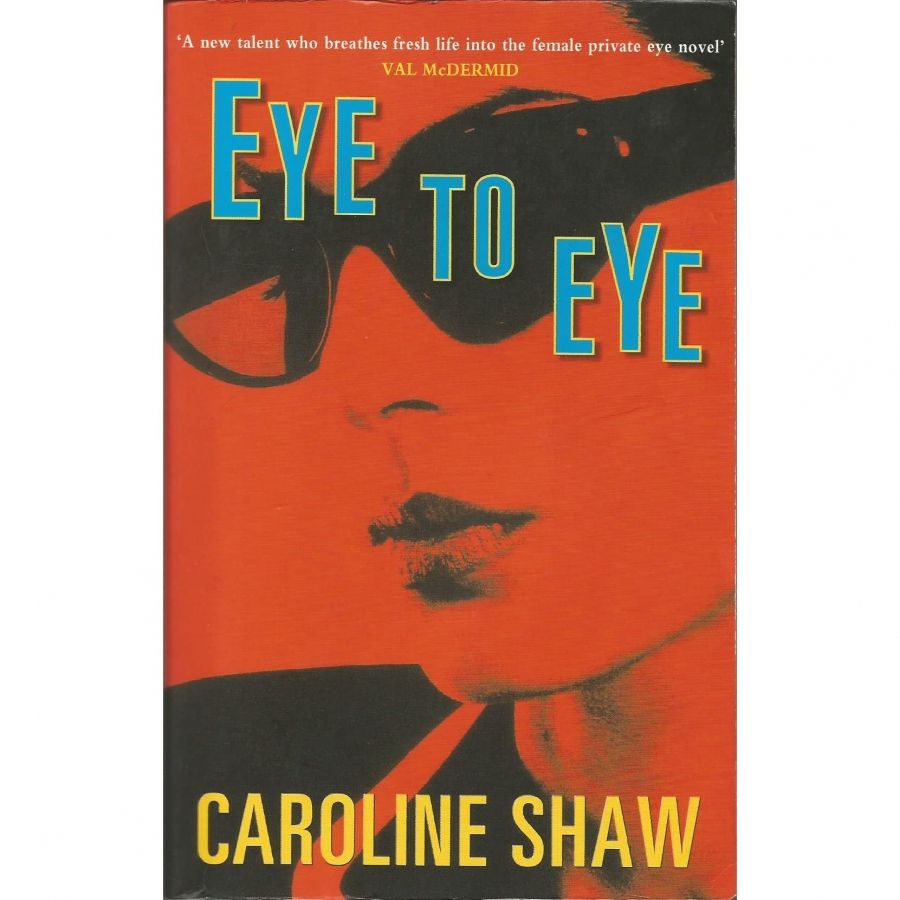

- Book 1 Title: Eye to Eye

- Book 1 Biblio: Bantam, $19.70 pb, 314 pp

There’s nothing cute about Lenny Aaron or her storefront business apprehending and returning missing cats: it’s a tooth and claw struggle to the finish with both parties bearing the scars. As a cat catcher, Lenny’s a whiz. As a private investigator, she gets the job done. As a human being, she has big problems. Shaw has precisely chosen the cat as Lenny Aaron’s familiar (in the witchcraft sense of the word): both are antisocial beings and unsentimental outsiders, ruthless, contrary, cranky, wily, and scrupulously clean. Eye to Eye takes place largely in the precious and pretentious world of a film-making conservatory. Equipment theft plagues the Aquinas (!) School of Film on the Fitzroy/Colling-wood border, and the insurance company retains Lenny to go undercover as a student. But there’s also been a murder – a slasher movie event involving throat-slitting and gouged eyeballs. Pretty soon there’s another one and Lenny’s ticking off a list of suspects in ways which are oddly old-fashioned. This is a return to The Old Dark House/Ten Little Indians situation: a group of dodgy people in a limited and isolated locale, Gothicry, deception, and bodies in the library (or in this case on the cutting-room floor). This retro move sits somewhat oddly in a novel which does so many other interesting things. The characters in the film school seem stagey and staged. It’s as if Shaw’s not quite sure if she’s really interested in them or just wants to send up what they stand for.

To be fair, the film school setting does enable Shaw to have some fun at the expense of Australian film. Asked to nominate the most important feature of Australian film over the last twenty-five years, the undercover Lenny offers ‘Bill Hunter’ to her surprised but appreciative classmates. Shaw also has a go at the Australian arts establishment and the tokenism involved in selecting students and their films on the basis of minority status, parental wealth, sexual favours, or cultural politics in a highly competitive film-funding environment.

But it’s not the murders-in-the-school plot which keeps us reading Eye to Eye or which makes it a seriously good crime novel. Lenny’s self-imposed isolation from her world and the people in it is at the centre of this novel. Clearly, Shaw is constructing this series as a journey of self-knowledge and healing for Lenny. In Cat Catcher, Lenny had to exorcise crippling fears and social stigmata arising from a horrific line-of-duty disfigurement and her subsequent resignation from the police force. In Eye to Eye, she must work through the death of her father and its consequences for her prickly relations with the mother and grandmother she wants out of her life.

Her spiritual guide and antagonist is a Japanese psychologist, Dr Koichi Sakuno, who is coldly unsparing of Lenny’s shortcomings. In Cat Catcher, his treatment involved training Bonsai trees, and cricket as a zen event. In Eye to Eye, Sakuno uses the inner discipline of kendo stick fighting, which goes sadly wrong as Lenny falls short of the goal, runs amok and becomes an urban legend (Komodo Man – unfair to tell more here), subsequently disgracing herself in a match with Sakuno. This is but one of the many chunks of Japanese language and culture which mark Lenny’s inner landscape, signs of an otherness at once wistful, exotic, romantic, and unattainable.

In this novel, Lenny must confront her substance abuse, compounded of arcane combinations of legal medicines to achieve various synergistic states. As she says, ‘Why the hell couldn’t the drug company just manufacture something with all the best ingredients combined? The Lenny Pill, that would make her feel nothing like Lenny.’

The Lenny character and the novels are sustained by the unresolved contradictions she increasingly articulates about herself: can her rejection of other people and her Swiftian repugnance at human uncleanliness continue to overcome her desire for contact and for love, whatever that might mean? For Lenny, it gradually and subtly emerges, love means lesbian love – but thus far her misanthropy is by far the stronger force.

Comments powered by CComment