- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Warrior’s Pride

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I have always been puzzled by society’s readiness to send their young men into battle, and that the young men go, and then tell such lies when they get home about what they saw when they looked on the face of battle. I hadn’t wondered about women, except to be glad that they were exempt from combat. Now comes Mischa Merz’s Bruising, which is about fear, aggression, and courage, and written out of her experience of one-to-one combat in the boxing ring.

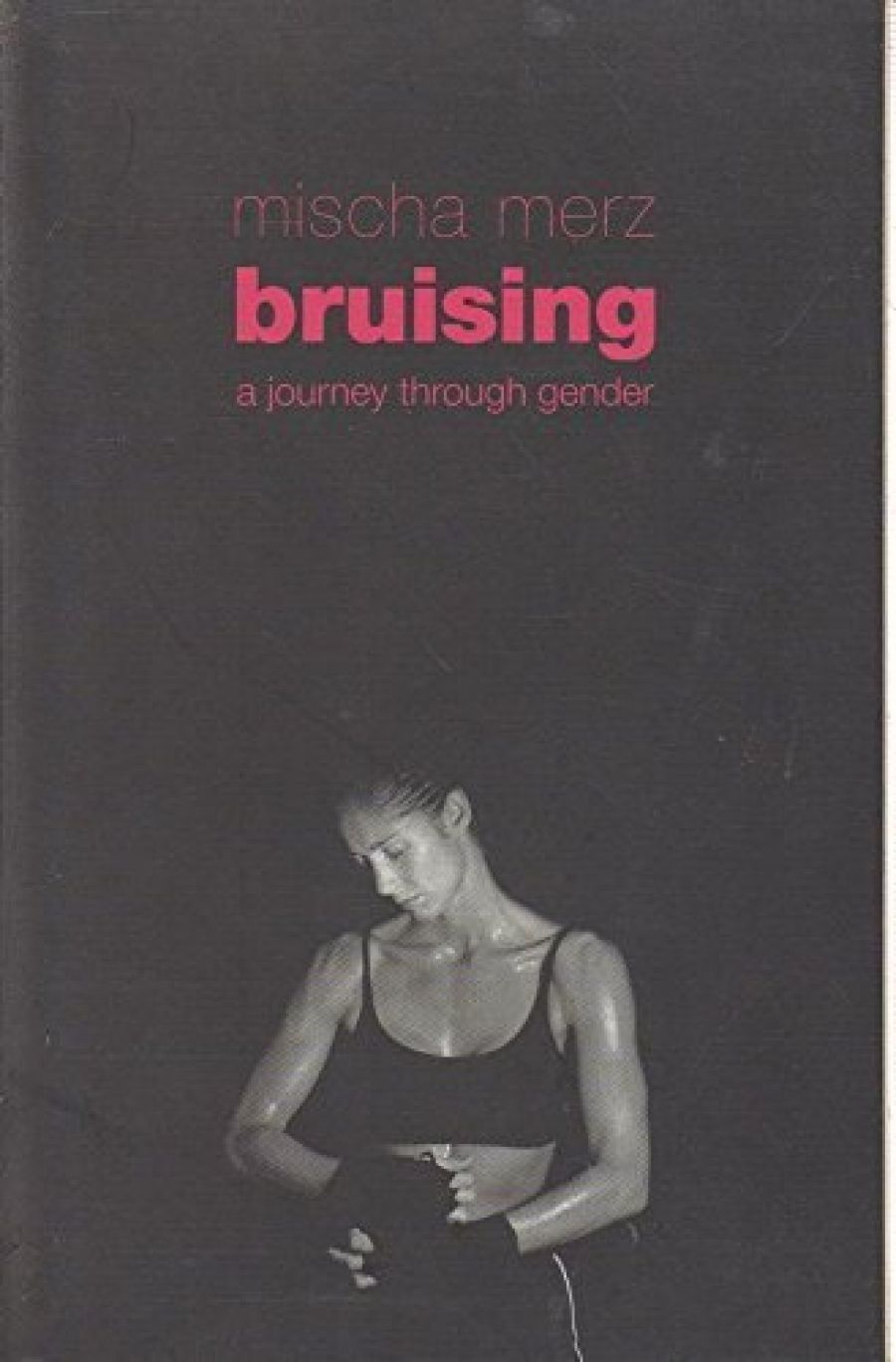

- Book 1 Title: Bruising

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Journey Through Gender

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador $20.78 pb, 255 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Now I have read Bruising and learnt a lot about boxing, about what has been happening to feminism since the 1970s, and about another Mischa Merz. (I have also had a very good time.) It all began when Merz is attacked by two women at the door of her St Kilda flat. Merz, to her own and their astonishment, routs them with a boxing stance and stylish left jab-and is left in a ‘snorting, puffing, highly aroused state’, longing for them to come back ‘so I could have another go at them’. She has discovered the illicit, unfeminine joys of aggression. But powerful inhibitions lie in wait: in the ring with her first woman sparring partner, each is terrified of hurting the other. They lurch around the ring to a verbal music of ‘Pow! Ouch! Sorry!’ in a Hesitation waltz of female shame at the idea of hitting someone for fun.

For the rest of the book Merz pursues and explores this explosive new emotion, suffers its pains, subdues its guilts, and initially tames it to her will. Through months of hard training, rough passages of panic and humiliation and some pain, she learns to look unflinchingly on the face of battle. There is some fine sports writing along the way, thick with the pungent immediacy not many people can make happen on the page. Merz also provides a shrewd commentary on feminist writing since the 1970s locating her personal struggle within a wider movement, and making this a useful book for anyone embarking on Women’s Studies. But while the theoretical material is handled deftly I was always glad to get back to the ring, because the ring is where the physical, emotional, social, and yes, the moral action is.

This is a quest narrative. With blinding honesty Merz uses herself as a measure of the plausibility of various hypotheses regarding the nature of the feminine as tested in fighting action. She also makes herself, her body, her mind, and her will objects of experiment, as she slowly learns the cost of courage.

To me, two generations older, even the pre-boxing Merz seemed a new kind of woman, managing obstacles and impediments not by slaloming around them, my generation’s technique, but by confronting them. She is totally undaunted by men: she feels no need either to placate or to impress them. She can be erotically roused by them; she likes them; on the whole she trusts them. And some men choose to help her, generously and without condescension. Stuart Patterson, a class professional boxer, gets into the ring and brings out the tighter in her, even if it’s not quite the fighter she had in mind. ‘In competition, Stuart rarely got hit, and he was careful to keep out of corners. He was quick and evasive and great to watch. He was helping me and I wanted to box just like him. “You’re a brawler,” he told me. I had to accept that.’

Then she takes herself off from her genteel middle-class city gym and her female trainer to Keith Ellis, a king in the small and shrinking world of male boxing whose kingdom is ‘a small tin shed next to a football oval in Melbourne’s west. Written on the shed in peeling rust-coloured paint are the words “Westside Champ Camp, Victoria’s most successful gym”.’ Inside are a rough tribe of committed boxers. Merz feels sensible trepidation she is, after all, invading working-class and very male territory. But she is at last penetrating the tough core of the boxing ethos:

I was seeing professional boxers push each other hard, and there was no way, in this gym, that I could convince myself or anyone else that boxing was only about movement and grace. Because here it was bloody and bruising and relentless. It needed to be. There was an imperative to edge as close as possible to unmanageable psychic panic in the gym before competing in the ring.

Merz has found a world whose values she honours. We watch her training her courage as well as her body until she is authentically intrepid: capable of being scared, but not of giving in. By the time she slips into the ring for her last fight she has no inclination to say ‘sorry’ when she hits and hurts an opponent: she is focussed, intent on winning as any boxer, male or female, ought to be. What matters most is the integration into the self of that initial flare of illicit excitement, which she has come to recognise as a legitimate emotion and an essential component of her moral being. She wants to win because she cannot tolerate the humiliation of defeat.

Merz has developed a warrior’s pride, a rarity even in her emancipated generation. The seventeen-year-olds who slip into the ring with her are a different breed again. It has never occurred to them to say ‘sorry,’ never occurred to them to feel guilty about inflicting hurt on a consenting fighter. They have been raised not on Tarzan’s Jane flitting around the tree-house but Xena: The Warrior Princess, that dim but noble woman with the crippling kick and the iron fists who knows that, in a world full of wickedness, courage is basic equipment, and violence the fast way to virtue. Merz’s last fight is for an Australian title at the Southport RSL. She loses honourably on points to a girl taller and faster than she is, and half her age. Meanwhile, the next generation waits in the wings: blond Zowie, eleven years old and scion of a lineage of boxers, takes less than a minute to clean up her opposition to her mother’s shrieks of motherly encouragement, ‘Straight punches, Zowie, ya dickhead.’

I knew the Mischa Merz who runs and surfs. Now I want you to meet Merz, the boxer who writes. You will enjoy it. And it might change your life.

Comments powered by CComment