- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

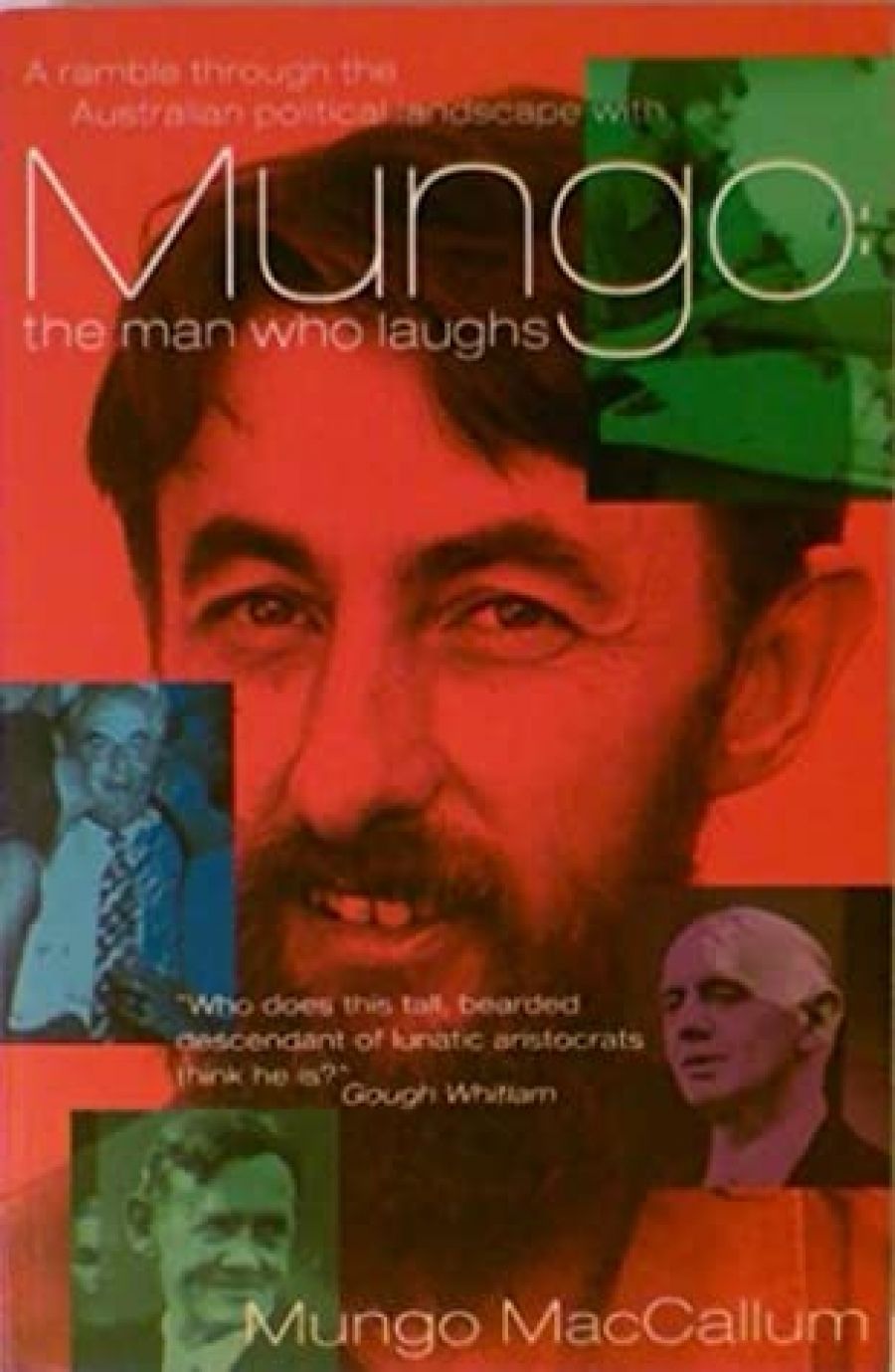

By the time I arrived in Canberra in the late 1970s, Mungo MacCallum was already a legend in his own lunchtime, which, as he admits in this latest book, ‘frequently dragged on towards sunset’. He was famed for introducing a new style of political journalism into Australia: irreverent, opinionated, witty, at times scurrilous. He was impatient of cant, and punctured pomposity. These qualities are all apparent in Mungo: The Man Who Laughs. It is avowedly neither autobiography nor history. It is an odd hybrid, divided distinctly into two parts: a set of autobiographical sketches devoted to his early life, laced with politics and laughter; and a personalised chronicle of the age of Gough Whitlam.

- Book 1 Title: Mungo

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Man Who Laughs

- Book 1 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $28pb, 292pp,

The scion of two great Sydney families – the Wentworths and the MacCallums – Mungo has fun with the aristocratic family tree, complaining of ‘worn-out genes’ and holding up for inspection a truly bizarre collection of relatives. His immediate family was rather dysfunctional: an alcoholic, Labor-leaning father, absent much of the time either at war or drying out; and a rather anonymous mother, perhaps too significant a figure for mockery. He skirts the traumas of family life, but his obsessive hunt in later life for a big brother – in the surrogate, rather than the Orwellian, sense – suggests how deep were the wounds. He first latched on to the novelist George Johnston as ‘the wise and experienced elder brother I never had’, and then the great editor of The Australian, Adrian Deamer, ‘became the second of my big brother substitutes’. The attachment to Gough Whitlam was the last, the most adult and the most enduring of these relationships.

His schooldays at Cranbrook were not happy; ‘a gawky and asthmatic smartarse’, he was an easy target for bullying. As with his relatives, his pen comes to his rescue: the headmaster, a social climber and philistine, ‘was a fossil and not altogether a convincing one at that: a sort of pedagogic version of Piltdown man’. University life was mostly extracurricular – theatre, revues, debating, Honi Soit; these, combined with ‘my pseudo-bohemian existence’, all led to a third-class honours degree in, of all things, mathematics. Then came the obligatory world trip, across Asia to Greece, where a pregnant girlfriend caught up with him. Marriage, an idyllic honeymoon and fatherhood in Greece were followed by a rather bleak year or so in England. The couple was rescued by their mothers, who brought the young family back to Australia.

These thin sketches are accompanied by a running political commentary whose central theme is how Mungo came to love the Left. It was not so much an intellectual as an emotional conversion, fuelled by distaste for his conservative relations and the social snobbery of his conformist school, and completed by the liberation of university life. A particular epiphany came at the age of nine, during the referendum campaign on banning the Communist Party. Young Mungo was waiting for his mother outside a shop when a woman climbed a ladder and began to harangue the crowd. ‘She turned an eagle eye towards me. “Do you want,” she screamed accusingly, “the secret police to have the right to break down the doors of your home and carry you off to jail without trial?” A moment’s thought convinced me that I did not.’

This juxtaposition of the political and the personal is an unsatisfactory one, the former frequently attenuating the latter. Political passages are often introduced at a point when the personal becomes too fraught or unbearable. It is as though ‘the man who laughs’ is fearful of tears. An unusual paragraph in which he puzzles as to why his mother clung to her marriage for twenty years is followed immediately by a section on Chifley, Menzies and bank nationalisation. ‘[P]retty broke and pretty miserable’ in ‘a lightless downstairs flat in Shepherd’s Bush’, relief comes through the Profumo affair and a discussion of the advantages of compulsory voting. This is politics as escapism.

In the second half of the book, the political is allowed to overwhelm the personal. In it, we have the tale of how Gulliver Whitlam conquered his Lilliputian rivals; how he was made vulnerable by his own flaws and even more so by those of the men around him; and how he was destroyed when ‘Kerr ejected prematurely’. There are some personal reflections on journalism, but the personal is now so sketchy that even Mungo’s major liaisons are difficult to decipher. The style is as supple and vivid as ever, pen portraits are memorable, and there are some wonderful set pieces, although much of it seems a reprise of material from his Nation Review days. I suspect I will not be alone in preferring the immediacy and the pointed details of those articles, collected in earlier MacCallum publications, to this nostalgic tale. Or perhaps, as the graffiti warns: ‘Nostalgia ain’t what it used to be.’

The book peters out with the fall of Whitlam. Mungo seems to have coped less well with the trauma of 1975 than even the Labor Party. He lingered on in Canberra into the 1980s but found Hawke’s Labor unsympathetic: ‘above all it lacked pizzazz.’ All that was left was nostalgia for the Whitlam years, ‘when no vision had seemed out of reach and no reform unattainable, when every day was another walk along the high wire to either glory or disaster’. So, he packed up his bags and his pen and sought paradise in Brunswick Heads.

Like all great clowns, Mungo MacCallum has probably a tragic perspective on the predicament of humankind, but, in this book, the clown’s grinning mask remains mostly in place. Yet the epigraph from Bertolt Brecht hints at the truth: ‘The man who laughs has not yet been told the terrible news.’ When Mungo MacCallum faces fully ‘the terrible news’ about himself, which he touches upon in this memoir but avoids by escaping into laughter and politics, then we could get one of the great Australian autobiographies. We might even learn if he really found paradise in Brunswick Heads.

Comments powered by CComment