- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Most of us are familiar with an image of David Unaipon, clean-shaven, neatly dressed, gazing steadily beyond the spatial dimensions of our $50 note. He wears a tie, and the collar of his shirt is evenly turned. Over his right shoulder is the little church at Raukkan; floating over his left are three of his inventions, including the shearing handpiece that no one would lend him the money to patent. And there is his signature, underneath the words: ‘As a full-blooded member of my race I think I may claim to be the first – but I hope, not the last – to produce an enduring record of our customs, beliefs and imaginings.’

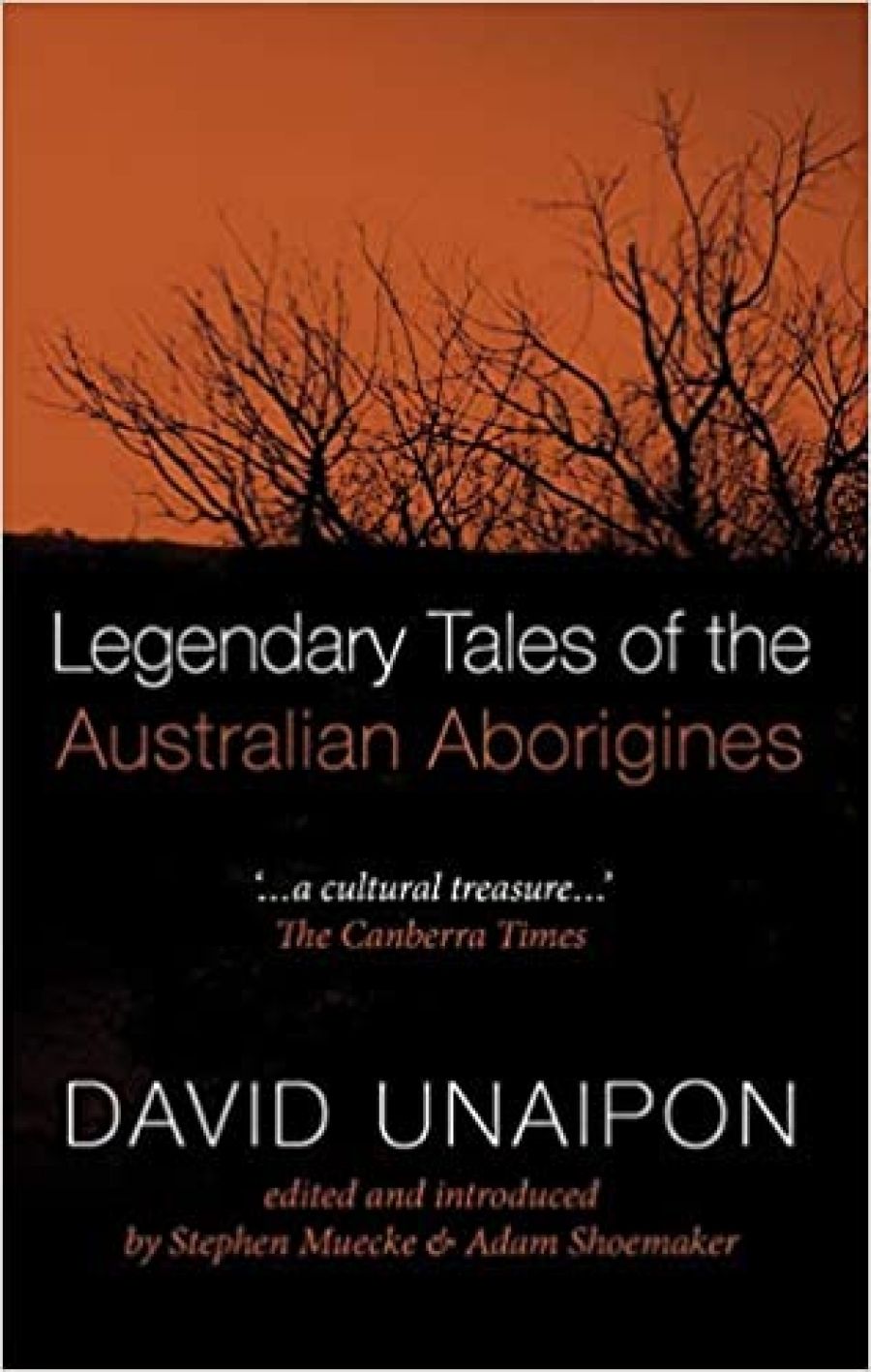

- Book 1 Title: Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $44.95 hb, 232 pp

Unaipon’s tales are the most extraordinary hybrids, representing what can happen when very different cultures collide and interact. Two worlds, at least, are represented in Unaipon’s work, and yet he belongs comfortably in neither. In the Legendary Tales he identifies freely with ‘my race’, while continually drawing attention to the ‘Aborigine’s primitive mind’ and ‘our little brain capacity’. He is of ‘them’, and apart: distanced from the ‘primitive’ beliefs and practices that, he claims at the end of ‘Witchcraft’, have ‘prevented the increase of my race’.

Unaipon collected ‘myths’ and ‘legends’ from more than his own Ngarrindjeri community. He moved beyond familiar territory, collecting stories for Angus and Robertson, who bought his work, including copyright, for ‘about £150’. The tales were collected from different narrators, recast and written down by Unaipon. To whom they actually belong, and the extent to which they are traditional or ‘authentic’, are exceptionally complex questions. Shoemaker and Muecke have restored Unaipon’s Legendary Tales, formerly subsumed in Ramsay Smith’s Myths & Legends of the Australian Aboriginals, to a version that is as close as possible to the manuscript Unaipon first produced. That is no mean feat. But it is not so easy to accept the editors’ claim that they have ‘repatriated’ the stories by bringing them ‘back to the people and country of their creation, to make the circle whole’. Can such stories really be ‘repatriated’? Don’t they exist somewhere between one country and another, like David Unaipon himself? The black Scotsman in suit and tie, with fob-watch and chain, rolling his r’s and travelling second class (not third) by train, remains an ambivalent figure.

There is no doubt that Unaipon creatively interpreted the ‘customs, beliefs and imaginings’ he collected. In ‘Aboriginal Folklore’, he writes: ‘Perhaps some day Australian writers will use Aboriginal myths and weave literature from them, the same as other writers have done with the Roman, Greek, Norse, and Arthurian legends.’ His own stories weave together Aboriginal and Christian myths, European literature and fairy tales. The effect is disconcerting and defies classification. The anthropologist Norman Tindale, thinking he was commenting on Ramsay Smith’s work, dismissed the tales as ‘romantic rubbish’ with ‘highly improbable conceits entirely foreign to the real stories of an Australian prelithic [sic] people’.

There are, in Legendary Tales, many passages of carefully wrought prose that are both beautiful and dramatic in their effect. Unaipon’s version of ‘Narroondarie’s Wives’, one of the most treasured traditional Ngarrindjeri stories, has already been anthologised in Paperbark (1990), a premier collection of Aboriginal writing, edited by Shoemaker and Muecke, with Jack Davis and Mudrooroo. ‘Wondangar Goon Na Ghun’ is equally remarkable and engaging in its narrative detail. The Wondangar (Whales) were a lazy tribe residing on the beaches of Australia. They were so lazy that they ‘would not even hunt for food, but lay in the shallow water and put their tongues out and wagged and wagged them until some of the fish would become curious and swim round and round, thinking what a funny sight’. They grew barnacles and exploited the kindly Goon Na Ghun (Star Fish) until those good people weakened and died. The Wondangar were banished to the sea, and their victims took the form and shape of stars. Good and bad: everything has its place. But the charm of this legend is in its telling. How much of the spark of stories like this one is attributable to the original tellers can never be answered. But there is no doubt that Unaipon used his imagination and acquired knowledge to create distinctive interpretations.

At times, undigested information and ideologies clog up the narratives. Animals preach sermons. People speak to each other in biblical language: ‘Eat, and thou shall be well because I have sought the best food for thee.’ Possibilities for imaginative play are cut short by determining Christian values and morality. Some of the stories, such as ‘How Teddy Lost His Tail’, are cast as nursery tales, in the way of Katie Langloh Parker’s Australian Legendary Tales: Folklore of the Noongaburrahs as Told to the Picaninnies (1896). Unaipon may well have been influenced by her example. However, most of Unaipon’s Legendary Tales are significantly more than nursery stories.

Unaipon insists in his Tales that myths are the basis of literature. All races, he writes, ‘have wrestled with the problem of good and evil’. All nations, he claims, ‘may accept and follow the teachings of a Budha [sic], a Mahomet, and Christ, each ... great men in their time and ... with us today’. Narroondarie, for Unaipon, is a prophet and philosopher like all prophets and philosophers. Unaipon looks for parallels. In the Christian tradition, he notes, ‘Evil still presents himself as the Serpent’ while ‘to the Aborigines he comes as a Crow’. His stories offer a syncretic worldview, assuming the potential for racial harmony.

If Unaipon’s stories are stylistically eclectic, most are charged with something unfamiliar and intriguing. Where his stories are most charged, Unaipon treads on dangerous ground. ‘Witchcraft’ elicits a voyeuristic fascination with the details of secret practices of ‘primitive’ men who use pointing sticks and bones, crystals and ropes of human hair and earwax, to bring about the deaths of enemies. As a dramatic narrative, ‘Witchcraft’ is an astounding piece of work. Writing mainly in the present tense, Unaipon takes his readers on journeys of revenge, through strange country, into the miamia of a victim who will surely die. While the motive behind the story is ostensibly demystification, and a warning that revenge practices are uncivilised and un-Christian, there is no disguising the ability of the storyteller to build suspense and create awe. Should Unaipon have revealed these secrets? Should I be reading about them?

Who will read these stories now? Already they have been classified on the flyleaf as Aboriginal Studies and Australian History. Why not Australian Literature? We’ve long paid lip service to David Unaipon as the first indigenous Australian writer, on the basis of pamphlets of stories he was known to have written. With the publication of this book, at last under his own name, we must take David Unaipon much more seriously. About time. If only he knew.

Comments powered by CComment