- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

J.M. Coetzee’s Stranger Shores is a collection of twenty-nine primarily literary essays dating from 1986 to 1999. It offers an impressive range of subjects, including a reappraisal of T.S. Eliot’s famous quest for the definition of a classic, a tracking down of Daniel Defoe’s game of autobiographical impersonations, and a biographical evaluation of ...

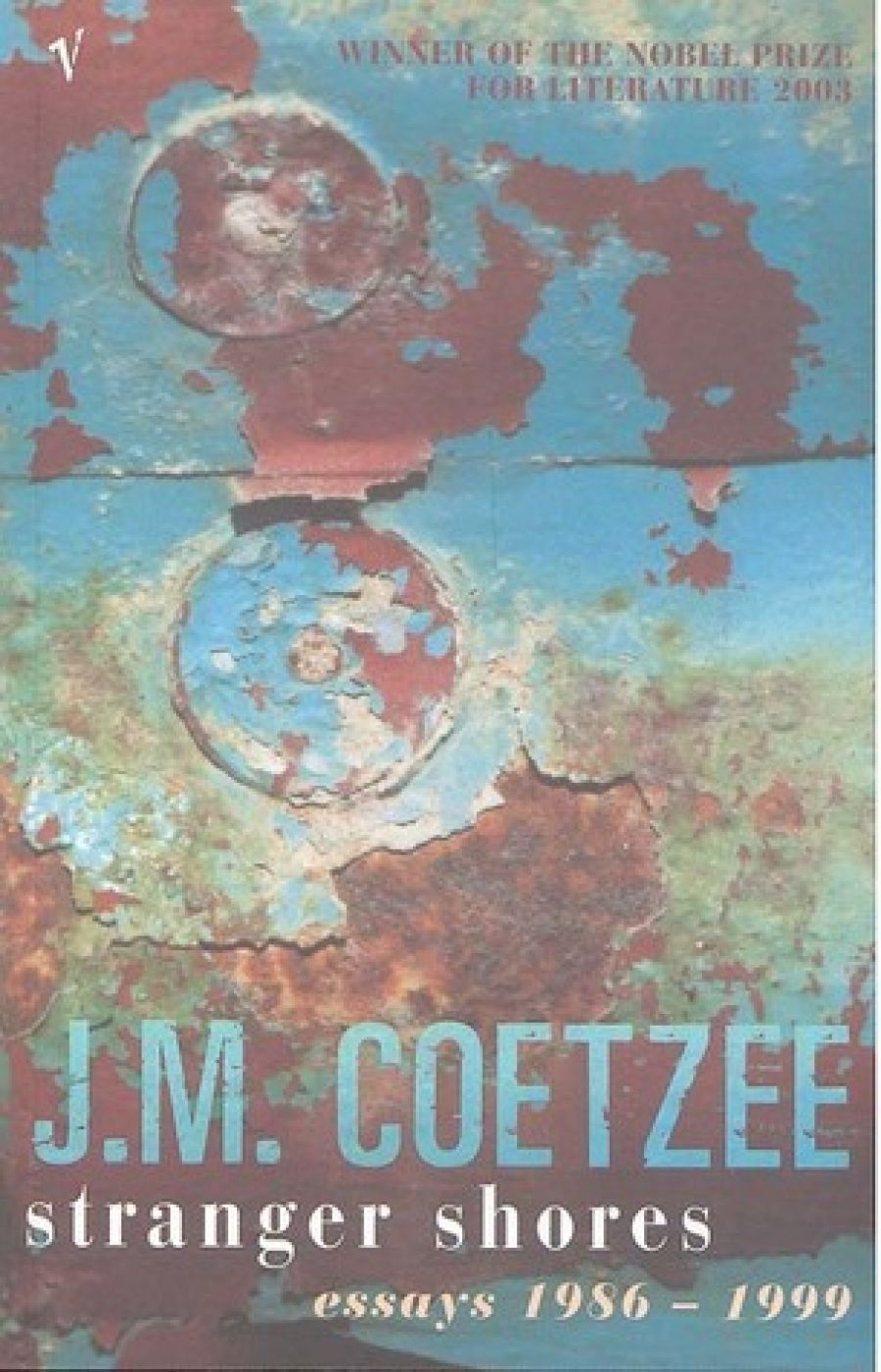

- Book 1 Title: Stranger Shores: Essays 1986–1999

- Book 1 Biblio: Secker & Warburg, $49.90 hb, 374 pp, 0436233916

In these knuckle-rappings, we hear the child of Coetzee’s autobiography, Boyhood (1997), who imagines himself as a teacher and announces rather forlornly and prophetically: ‘He is good at school, there is nothing else he knows of that he is good at, therefore he will stay on at school, moving up through the ranks.’ Coetzee did indeed move up through the ranks. He is now a professor of general literature at the University of Cape Town, and there is, throughout this book of essays, a strong sense that he knows his subject well. Competence, however, does not add up to excitement. What the volume boasts in tones of correctness and correction, it fails to achieve in the current favourite aesthetic measure: affect.

Coetzee’s relationship with literature, at least as expressed in these essays, is at once intimate and curiously without affection. Some readers may even expect this kind of reticence from an author who portrayed his protagonists in Foe (1986), based on Defoe’s characters Robinson Crusoe and Friday, as possessing too little desire, and whose more recent Booker Prize novel, Disgrace (1999), challenges us to weigh perversions of moderation against perversions of excess. Other readers may wonder if academics inevitably find it difficult to sweeten their didactic voice.

Coetzee’s essay on the Israeli writer Amos Oz begins: ‘In autobiographies of childhood the first moral crisis often looms large – the moment when the child faces for the first time a choice between right and wrong action. It is a moment which, in retrospect, the autobiographer recognises as having had a formative effect.’ Formative influences and rites of passage dominate Coetzee’s work. In Disgrace, a cocky university professor who presents himself as a self-searching disciple of Wordsworth and a self-satisfying servant of Eros, is tracked spiralling down through various hells of humiliation, to end on the lowest rung of disgrace, below the dog whose life he chooses not to save. There’s also a dog left to die in The Master of Petersburg (1994), a novel about grief and the cold abstraction of grief. And in Boyhood, a dog run over by a car, coupled with the secret guilt of abandonment, constitutes the author’s earliest childhood memory. In each case, chillingly, the author serves up the literary conundrum that, of course, these are not real dogs, regardless of how much sympathy we may have invested in them and in other imagined ‘victims’ of literary representation, especially women and children. Coetzee delights in the establishing and undercutting of his, and others’, fictions. If he is a joker, then the joke is on us, the seduced, gullible, tail-wagging reader. We are the Coetzeean underdog.

Meekly we ask, at the end of Disgrace, why the dog had to die. In Stranger Shores, a similar question arises from Coetzee’s discussion of Samuel Richardson’s heroine, Clarissa: ‘Why must she die? This is the question Richardson asks and answers, even though – to his eternal credit – his answer alienates him from his readers and perhaps from himself too, as he knew himself.’ Coetzee’s answer, the short answer, is that, after she is raped, Clarissa is no longer herself, as she knows herself. Like the dog’s, her death is reduced to Coetzee’s logic, which readers would not always share, especially since it does not consider a veritable epidemic of post-Clarissa heroines – Lucy Ashton, Hedda Gabler, Anna Karenina, Effie Briest, Emma Bovary – whose suicides are arranged by male authors.

Self-alienation and, in turn, the alienation of the reader, define Coetzee’s existentialist credo. It is odd, therefore, that his essays do not include a discussion of Camus, because his ‘strangers’ are close relatives of L’Etranger. With each subject, Coetzee continues to eke out the condition of the outsider. He finds that a certain amount of prudence is a prerequisite of survival in a difficult world. ‘Part of being prudent,’ he says in Boyhood, ‘is always to tell less rather than more.’ Therefore, Coetzee the critic can understand the Russian writer Joseph Brodsky’s fear of openness and his cultivation of a protective irony, or the South African Breyten Breytenbach’s identification with the insecure fate of cultural bastardy, which ‘entails a continual making and unmaking of the self’.

Reasons for keeping oneself in check, for masking and unmasking, particularly as this is reflected in the lives of exiled writers such as T.S. Eliot, Robert Musil, or Joseph Skvorecky, are Coetzee’s special domain. To explain the complex of Eliot’s motives for becoming English, he proposes not just Eliot’s anglophilia or his solidarity with the English middle class, but also the poet’s adoption of ‘a protective disguise in which a certain embarrassment about American barbarousness may have figured’. Issues of barbarism and survival enter into Coetzee’s essays as obsessively as they dominate his fiction. Putting his own spin on Eliot’s definition of the classic, Coetzee argues that ‘what survives the worst of barbarism, surviving because generations of people cannot afford to let go of it and therefore hold on to it at all costs – that is the classic’.

If one takes into account his Boyhood confession that ‘he shares nothing with his mother’ and that ‘he knows that he will fly into a rage if she ever begins hovering over him’, as well as the fact that ‘he wants his father to beat him’ but ‘if his father were to hit him, he would go mad: he would become possessed, like a rat in a corner’, then an idiosyncratic pattern of anxieties about (signifying a desire for?) control and loss of control, shadowing issues of survival and barbarism, shifts into view.

Coetzee’s literary world is sheathed with anxiety about the uses and abuses of hierarchy. It seems to matter terribly who’s on top (who hovers, who beats), and who’s underneath. Sexual, generational, territorial, and metaphysical interrogations of power, influence, and position fold into and wrap around his essays as much as his narratives. He retraces Musil’s ‘mystical-erotic withdrawal from society’, Dostoevsky’s concern for fatherhood (in the flesh and in the abstract), Eliot’s for the classic, and Brodsky’s for lineage.

In Boyhood, Coetzee does not like his father and ‘never worked out the position of the father in the household’. This kind of confusion breeds many shades of guilt, and a strange and strained economy of ethics and emotions. Towards the mother, the child feels that ‘never will he be able to pay back all the love she pours out upon him’. He wears estrangement like a crown as he travels between Boyhood, his novels, and Stranger Shores, along the autobiographical, fictional, and scholarly trajectories of his life and work, casting a pall of negation over everything he writes. In the end, Coetzee is a somewhat testingly old-fashioned Outsider-figure, and his latest collection is admirable, but a little dry.

Comments powered by CComment