- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Anyone for Venice?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is something irresistible about trying to trace a connection between notorious lover and memoirist Casanova and notorious lover and poet Lord Byron in Venice – the seductive city where both men worked their way through galleries of women. Casanova estimated that he had had more than one hundred and thirty in 1798, the year of his death, although that was his lifetime’s count, not just the Venetian episodes. Byron, on the other hand, reckoned that he had got through more than two hundred in Venice alone – and in less than two years – before he stopped counting. Between their frenzied trysts was a tantalisingly small gap of thirty-odd years: Casanova was sent into his final exile from Venice in 1782, before Byron was born; Byron arrived in 1816. People who had known the Italian must have met the Englishman.

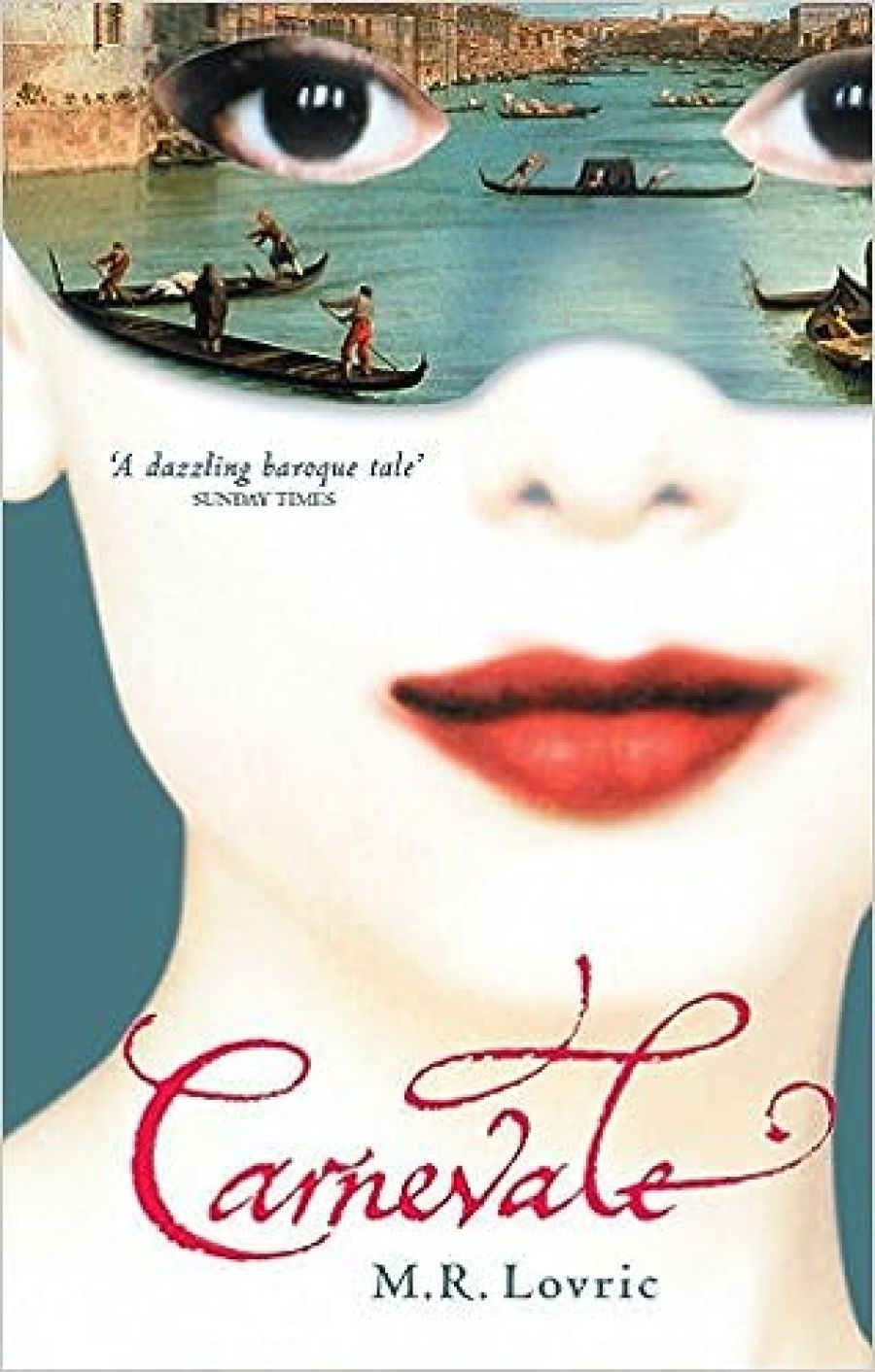

- Book 1 Title: Carnevale

- Book 1 Biblio: Virago, $35 pb, 634 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Maybe Casanovrians play the same game that Byronists play: the search for the missing link, the one unknown woman who will make sense of some strange bits of Byron’s life. M.R. Lovric, in her first novel, has gone one better, conjuring not only the woman who makes sense of Casanova’s story, but who, thirty-odd years later, solves Byron’s story as well. She is Cecilia Cornaro, a precociously gifted portraitist who becomes, at thirteen, Casanova’s last love and, at forty, one of Byron’s first.

This is a lush book, dripping with opulent descriptions and elegant imagery. It is Venice at its most overblown. The almost overwhelming catalogue of richness is partly licensed by Cecilia’s occupation: give your narrative to a painter, and it would be strange if you weren’t flooded with visual impressions.

The story that sits under this richness is a fairly simple one: love letters undelivered, good men and bad men, illegitimate children, epiphanies. The thirteen-year-old Cecilia’s speedy seduction by Casanova and her unbelievably immediate success as an artist give way to the nub of the book: the gnarled and awful ‘love’ that Cecilia feels for mad, bad and dangerous Lord Byron. Having fallen for him in 1809, before he became famous, she cannot shake herself free from him or his ill-mannered and selfish behaviour as a lover, even while he leaves her ignominiously and disappears from her life for seven years.

To take the silhouettes of these two most famous of men and flesh them out kick-starts the book: their very names are shorthand for particular kinds of characters. The interesting thing is that, even in the face of their familiarity, it is the character of Venice that Lovric invigorates most. There are gems of information about how the city looked and smelt and lived: ‘books’, you learn, ‘were sold by weight, like sugar’, and the waters trailed ‘funeral gondolas lurching like sobs’. But sometimes this stuff of historic veracity caves in under its own weight, and you’re left skimming its list, waiting for the story to pick up again.

Still, the ways in which pieces of ‘fact’ are wrestled into the ‘fiction’ of this novel are deft. Goethe is allowed to come to Venice and to sit for a Cecilia Cornaro portrait, so that he can throw in an appropriate German proverb and, later, protest to Cecilia about Byron’s plagiarism of Faust. Your acceptance of a thirteen-year-old’s passionate and lascivious affair is made easier with the line that men of Casanova’s age prefer their mistresses to be Juliets: with that one universal reference, Cecilia’s age becomes unquestionable. The chronology is obscured sometimes, and Byron’s reaction to the memory of Casanova never quite gels as it probably should. But this sense, like noticing a couple of inaccuracies in Byron’s history, probably springs from being a reader who knows too much about Byron in the first place. Reading the book after being obsessed with one of the characters is entirely different from reading it as a story with a couple of familiar names.

At the height of her own obsession with the absent Byron, Cecilia asks herself: ‘But what kind of love is this, which is so greedy and needy? Which feeds not on caresses but second-hand stories and gossip from the street? Which muses alone for quiet hours and acts stealthily in the night? It is an unrequited love, of course, a love that is not satisfied in the ways that demand satisfaction.’ It is also a fitting description of both biography and of what Lovric herself has achieved in this ambitiously imagined book.

Lord Byron, recently arrived in Venice, is said to have seen Casanova’s name carved into a column, the letters worn away by the years. He chipped them in again, fresh. Carnevale refreshes the names of both men and, most grandly, the city they played in.

Comments powered by CComment