- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Case for Cannabis

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a book about pain. In December 1999, Arthur Reilly was diagnosed with life-threatening cancer. The methods of relief offered to him, principally morphine, had drastic side-effects which undermined what pleasure he might have found in living. For four months, he lost weight and showed little interest in his usual activities. He became depressed and contemplated suicide.

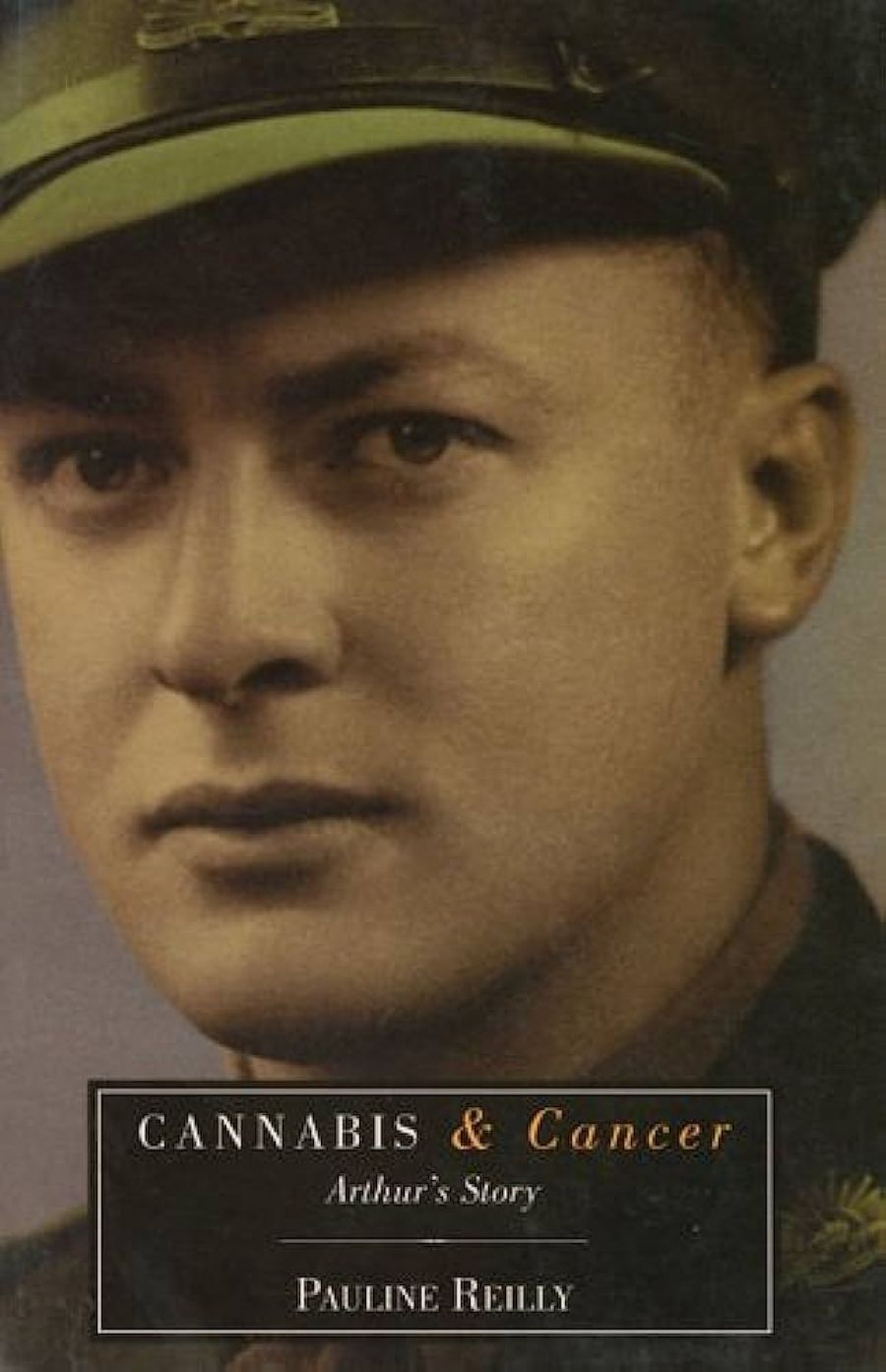

- Book 1 Title: Cannabis and Cancer

- Book 1 Subtitle: Arthur’s Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $19.95 pb, 118 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Pauline, his wife of almost sixty years and a prolific natural history author, emerges from her account of the last eleven months of Arthur’s life as a woman who is not easily defeated. Friends suggested the use of cannabis, a drug with which Pauline had little familiarity. But she was willing to try it. In her eighties, she became a convert to the use of a substance often associated with youth and mild forms of social protest. She gently mocks the idea of two octogenarians slipping onto the wrong side of the law. But Arthur found that cannabis cookies really did help. His appetite returned, and he became more active. He could avoid the severe nausea occasioned by morphine. Once Pauline saw the effects of the drug on her husband, she became deadly serious about it. She wanted to know why it was not available for medical use.

Cannabis and Cancer is really a kind of personal essay. It is a sustained argument for a more open social and medical attitude to cannabis. The author has a point to make and never allows that point to move out of focus. She makes accessible an impressive range of research into the subject. She also offers a recipe for marijuana biscuits. Her work is sustained by a breathtaking ability to salvage something positive for others from her own loss. Arthur died in November 2000. Pauline continues to campaign.

It may be churlish to comment on the book the author has chosen not to write, but Pauline Reilly is obviously no stranger to pain at many levels. The margins of this book contain plenty of hints that both she and Arthur had to cope with loss in various circumstances. The pair met during World War II. Arthur saw active service in New Guinea, Europe and the Middle East. Pauline worked in military intelligence. They buried one of their sons when he was twenty-one. He had suffered from a blood disease for seven years, and Pauline wonders, in passing, if cannabis might have relieved his ordeal. Pauline reproduces the chronology of Arthur’s life that she wrote when he died. In a single line, she mentions that the pair lost everything in the Ash Wednesday fires in 1983.

I winced when I read that. But there is no self-pity in this book. Indeed, when Arthur died, Pauline read a book about trauma. She passes on the information she found: ‘the pituitary secretes hormones that trigger reactions in the adrenal glands and the immune system. This initially causes numbness, and then, a few days later, the need to shed tears in order to rid the body of the chemicals generated. So we cry and feel much better for it.’ Pauline is actively compassionate towards those who suffer. She doubtless understands as well as anyone that there is much more to grief than physiology, but that is one side of life she chooses not to explore in public.

This is not a book without humour. Pauline refers to her ‘pot plants’. She is amused by the shadowy cannabis supplier who explains that his price increase has been caused by his obligation to charge GST. Nor is it a book without fear. Pauline has nightmares about being arrested because of what she is doing to help her husband.

Part of the appeal of Cannabis and Cancer is that it is written by someone for whom breaking the law does not come easily. Her natural instinct is to want to change the law. She documents her correspondence with the Victorian Premier, Mr Bracks, and various government officials. She details law reform in other parts of the world. She offers statistics to show that the availability of marijuana for medical purposes does not tend to increase its recreational use in the community. She tells stories of people around the world who have been dealt with harshly by courts despite the fact that their use of marijuana was patently necessary. Her case is formidable.

This is an example of a story in which a single personal experience starts to send ripples through a community and to create bonds with people who have shared similar experiences. Of course, there are those who also testify personally to negative experiences occasioned by cannabis. In his introduction, David Penington alludes to some of the most painful of these: those for whom marijuana has activated a predisposition to schizophrenia. But this book argues within boundaries that do not overlap with such cases. Its pragmatic compassion is sharply focused.

Comments powered by CComment