- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Nature Writing

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tales of Extinction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

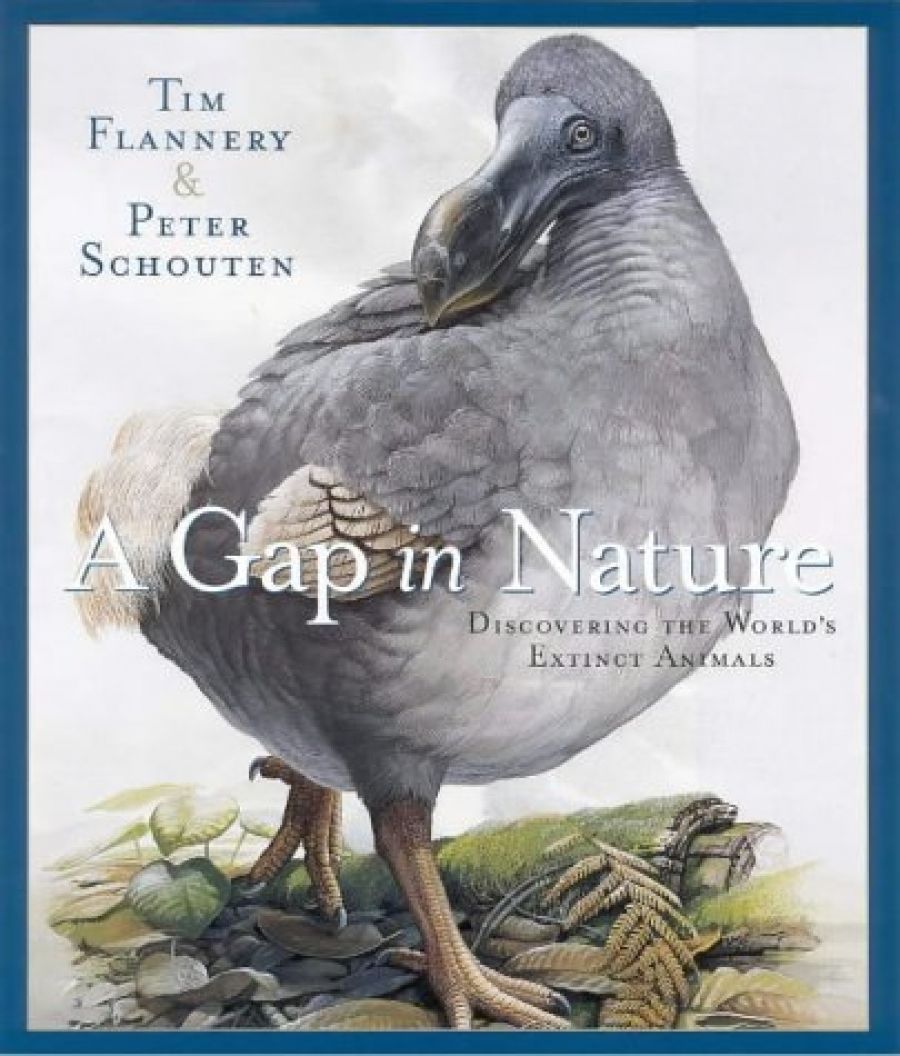

It is too heavy to read in bed or on an aeroplane, too handsome to besmirch at the beach, would court disaster if tackled at the kitchen table, and there’s no room on my always-littered desk. It’s the sort of book that, in its size and splendour, is aimed at the coffee table. Yet volumes like this seem more at home on television, their contents rendered into documentaries introduced by David Attenborough. - Book 1 Title: A Gap in Nature

- Book 1 Subtitle: Discovering the world’s extinct animals

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $50 hb, 208 pp

The first thing that has to be said about this book is that it is a spectacular production: more than two hundred 25 cm x 29 cm pages betwixt the hardest of covers. But do these qualities obviate one’s reluctance to read the saddest of sad stories? The topic of animal extinctions reminds us that human beings are the nastiest of neighbours whose sins of omission and commission are proving fatal to more and more of our feathered, finned and furry friends.

Not that humans should bear the entire burden of guilt. In writing on related matters, the likes of Stephen Jay Gould remind us that natural selection, in all its promiscuity and fecundity, produces untold billions of failed species. But does that mean we should shrug off extinctions? Emphatically no, says Tim Flannery:

Extinction must be regarded over the vastness of evolutionary time as the fate of all species – as unavoidable as death and taxes. Some people, economists among them, have used this insight to argue that there is no need to worry about the extinctions of species in the modern world. Theirs, however, is a flawed reasoning, for there are periods in history when the rate of extinction is so rapid that whole ecosystems are destabilised and swept away. Then the earth becomes a less productive, less stable and more impoverished place.

Flannery has been telling us for years how our mega-fauna was ‘swept away at around the time the ancestors of the Aboriginals arrived on the continent, some 46,000 years ago’. It’s an argument that has, because of its political implications, mired him in controversy. In this book, however, he focuses on the last five hundred years when there were many islands scattered around the world that humans hadn’t reached, ‘which retained faunas that were a faint echo of this grand world’. Then came Columbus’s adventure of 1492 and a new wave of European expansionism. In Australia, white settlement has meant ‘one in every ten of Australia’s unique mammal species’ is now extinct.

A Gap in Nature, four years in preparation, attempts to resurrect this vanished world, to show us what we’ve lost. In his introductory essay, Flannery provides the criteria for selecting a species for the book. ‘It must be a mammal, bird or reptile whose extinction occurred between 1500 and 1999. It must be known from material sufficiently adequate to allow accurate illustrations to be made. It must be accepted that the organism in question represents a full species, not a subspecies. It must be widely accepted that the species is extinct.’

The animals missing in action now live on in the paintings by Peter Schouten. Reproduced from life-size originals, the images are equally tragic and beautiful. The way they are rendered is unbearably confronting. Each bird and animal looks at you with a mixture of dignity and desolation. I’ve never seen sadder eyes. These paintings have a religious quality, speaking to collective guilt, if not original sin. The expression in those eyes couldn’t be more reproachful.

The most celebrated of recent extinctions, the dodo, con-fronts us on the cover, reminding me of the Hilaire Belloc poem I used to read my five-year-old daughter: ‘The voice that used to squeak and squeak / is now forever dumb. / Yet you may see his bones and beak / All in a Mu-se-um.’

But the mu-se-ums are almost empty of reliquaries containing fragments of the martyr’d dodo. Flannery describes a visit to the Ashmolean in Oxford and the privilege of having the dodo’s skull ‘placed reverently’ in his hands.

In the big scheme of things, do our recent and accelerating extinctions really matter – species dropping off along the way as the human race prepares, perhaps, for its own oblivion? Should we simply look forward to all the amusing hybrids (tongue of bat, eye of newt) being put together in the witch’s cauldron of the genetics laboratory? With all this scientific conjuring of new species, what does it matter that we’ve lost the Falkland Islands’ dog? The massive Steller’s Sea Cow? The Upland Moa? The Great Auk? The Thylacine?

Well, it matters when you find them looking at you from the pages of this book. Provided, of course, you can find somewhere suitable to read it.

Comments powered by CComment