- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Any book documenting the life and work of a famous artist invariably paints a picture of an era. This autobiography by the outstanding Australian contralto Lauris Elms is no exception. The postwar years in Australia saw the emergence of so many talented young singers that one can’t help but label that period a ‘golden age’. At a time when many of them, almost by necessity, departed for Europe or the UK, their combined successes on the world opera stage never ceases to amaze. An enviable standard was set which has been maintained to this day, even if the individual successes are not quite so spectacular.

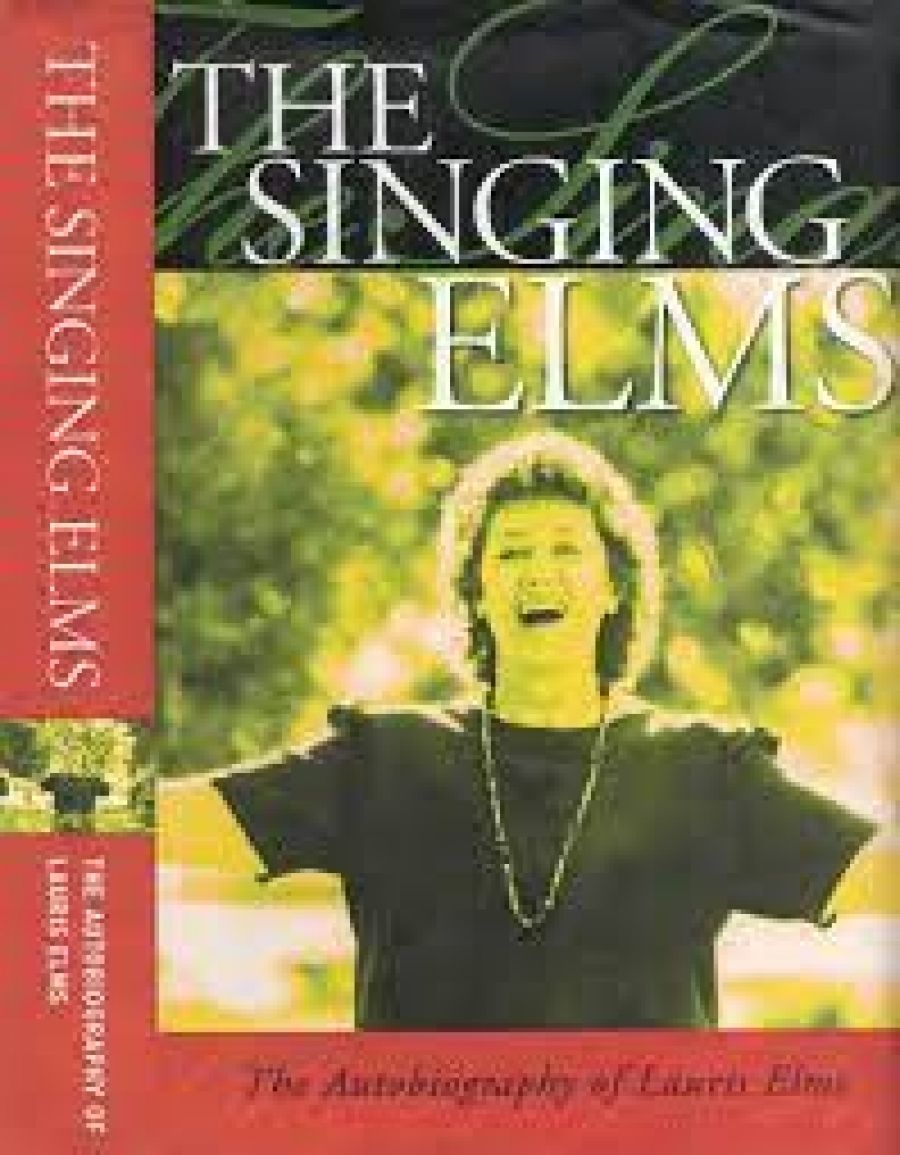

- Book 1 Title: The Singing Elms

- Book 1 Subtitle: The autobiography of Lauris Elms

- Book 1 Biblio: Bowerbird Press, $32.95 pb, 296 pp

Lauris Elms’s career was a success by anyone’s standards. That she may have achieved even greater fame had she stayed in Europe is debatable. Her decision to return to Australia was probably the right one, especially as she chose to combine her career and motherhood in her homeland.

Elms was born in outer-suburban Melbourne in 1931. Her early years revealed signs of an artistic temperament, with a flair for both music and art. Presbyterian Ladies’ College in East Melbourne was renowned for its cultivation of independence. Young Lauris was a perfect example. She overcame parental resistance and left school to study art at Swinburne Technical College. Inspired by hearing the young Marie Collier, Lauris sought lessons from the soprano’s vocal teacher. This led to classes under Gertrude Johnson at the National Theatre, an admirable organisation which also spawned the careers of Elizabeth Fretwell, Neil Warren-Smith, Lance Ingram, and Robert Allman, several of whom she later met in Europe when all their careers were ascending. Her operatic début was in the National Theatre’s 1953 production of Menotti’s The Consul, directed by Stephan Haag.

A meeting with the Paris-based singing teacher Dominique Modesti and his Australian-born wife was arranged when they were visiting Melbourne. They sought a contralto ‘like Kathleen Ferrier’, and were impressed enough to offer Elms two years’ free tuition in Paris, for which she departed in December 1954. They were years of re-learning her vocal technique and discovering the world of international opera, all of which makes fascinating reading.

By 1957, she was invited to join the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. At that time, more than half of the principal singers were Australian. Her roles included Ulrica in Un Ballo in Maschera, Anna in The Trojans, and Mother Jeanne in Dialogues of the Carmelites, the latter also featuring the young Joan Sutherland. She would also share the role of Alisa (with Margreta Elkins) in the famous 1959 Zeffirelli production of Lucia di Lammermoor that made Sutherland a star.

Elms married in 1958. After her husband’s university appointment the following year, the couple returned to Australia. The next years were a combination of concert recitals and the life of a College Warden’s wife. The arrival of a daughter in 1960 brought another role of a different kind. Recital engagements increased, both in Australia and New Zealand, throughout the 1960s. Works by Schubert, Mahler, Bach, and Elgar predominated, with frequent performances of Handel’s Messiah, Mendelssohn’s Elijah and Verdi’s Requiem – to the acclaim of audiences and critics alike. Elms became established as one of Australia’s finest recitalists.

The glorious Sutherland-Williamson Season of 1965 brought Elms back into opera mode. She performed in six different works presented by prestigious casts including Elizabeth Harwood, Luciano Pavarotti, and Spiro Malas, as well as Sutherland, Allman, and John Shaw. Her roles included Olga in Eugene Onegin and Arsace in Semiramide, the latter work little known at that time. The link with Sutherland and Bonynge was enhanced a few years later when she recorded Montezuma by Graun and Griselda by Bononcini.

During the years that followed, Elms was a mainstay of both opera and concerts in this country. She performed a wide range of operatic roles with the emerging national company. Handel’s Julius Caesar, Verdi’s Amneris in Aida, and Azucena in Il Trovatore were especially memorable. But Elms also brought to appreciative audiences lesser-known characterisations, including Gluck’s Orpheus and Britten’s Lucretia. Mrs Sedley in Peter Grimes was another Britten portrayal and one which she immortalised in the recording of the work conducted by the composer. Yet her concert work predominated, and one senses that this is where her preferences lay. She also performed the works of many Australian composers, which, at that time, was considered courageous.

Similarly brave was her forthright attitude to institutions and organisations with which she worked. Her criticism of the ABC (for good reason) and her views of the then Australian Opera, at a management level did not always please her colleagues. But few would deny that her motives were genuine and her ideals high.

The book includes a catalogue of performances and discography, which is essential in a work of this kind. Major events such as the opening of the Sydney Opera House in 1973 are well covered. A minor but constant irritation is her labelling the Victoria State Opera as the ‘Victorian’ State Opera. A few other inaccuracies that should have been picked up in proofreading include the renaming of the Victorian Premier as Sir ‘Richard’ instead of Sir Rupert Hamer. But, in the main, this is an enjoyable book. It will be welcomed by any music lover with an interest in the opera and recital scene in Australia in the second half of the twentieth century.

Comments powered by CComment