- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is one of the most satisfying and fascinating monographs on an Australian artist that I have read. Only Franz Philipp’s monograph on Arthur Boyd can be compared to it, and for quite other reasons. Catalano, lucidly and meticulously, unravels the complex physical and intellectual life of Rick Amor from the time of his boyhood. He discloses how Amor’s paintings depend on his ability to make his past the vehicle and inspiration of his creative achievements. It is a reflexive art embodying the omnipresent power of a memory touched with a redolent melancholy. His past is revealed as a strange presence that is not to be found in the work, in my experience, of any other Australian artist.

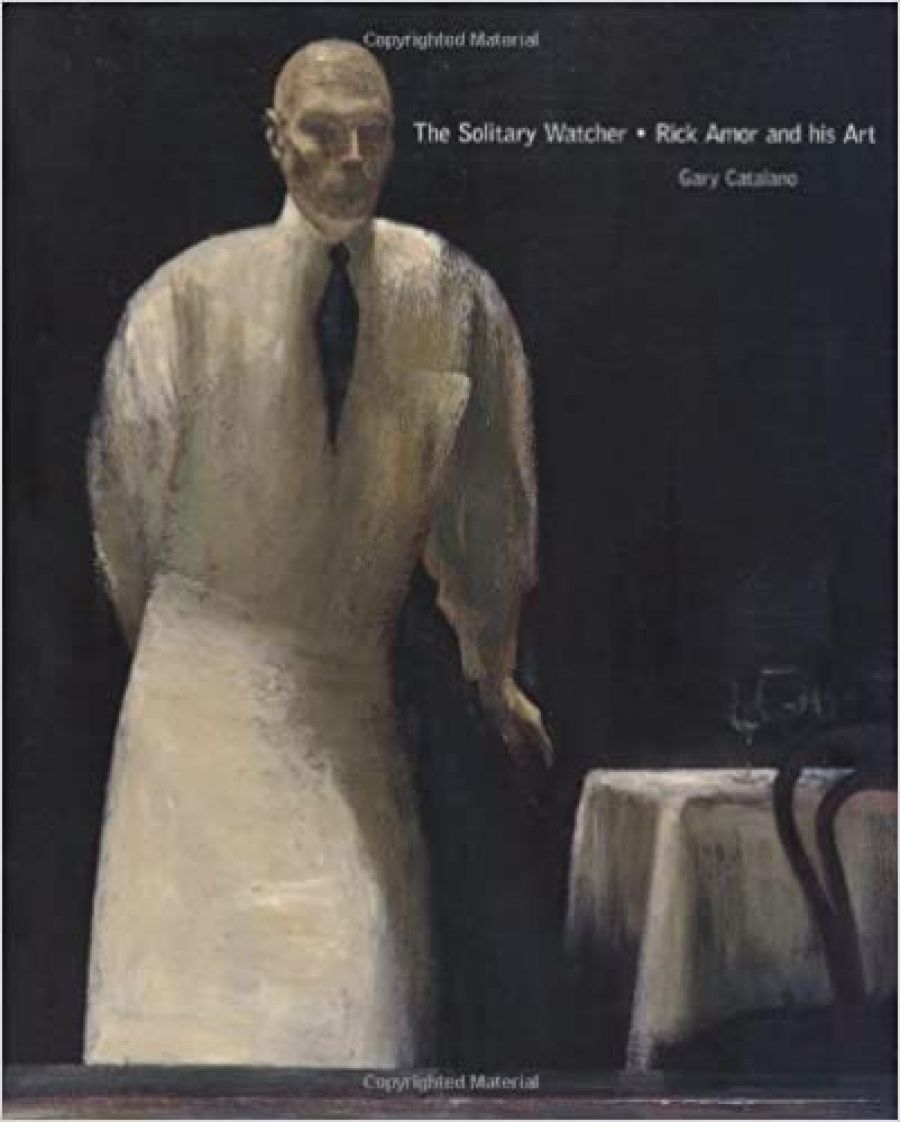

- Book 1 Title: The Solitary Watcher

- Book 1 Subtitle: Rick Amor and his art

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $89.95 hb, 215 pp

Catalano patiently reveals the influence of Amor’s boyhood environment in Frankston, in the ambience of his aunt, the writer Myra Morris, and her circle of friends; then that of his teachers John Brack and Ian Armstrong; his deep involvement in Left politics during the 1970s; the power of the poetry of Eliot and Auden, the metaphysical pessimism of Kafka, and his admiration for Edward Hopper, that superb American painter, who also painted against the grain of his time. At bottom, Amor’s art might be viewed as flotsam from the Enlightenment washed onto an Antipodean beachhead. But there is more to it than that. Mercifully, it does not re-enact the universalising fantasies of that abstract art so ardently promoted by theosophical thought during the early years of last century. It seeks its own place and its own time.

What emerges, among other things, is a more historic, more eerie, and profound image of the city of Melbourne. For the boy from Frankston, the city held the lure of mystery. He entered it as a stranger seeking to probe its pretentious grandeur through the eyes of his solitude. A painting such as The End of the Arcade reminds me of one of those famous prison etchings by Piranesi stripped of its Baroque excesses. Amor is a disenchanted flaneur in search of Melbourne’s voids and menacing silences. It is not everyone’s Melbourne, but it’s his, and I am sure that it will endure.

Yosyl Bergner and Albert Tucker were probably the first painters to provide us with this darker Melbourne, and Amor draws it again to our notice. It is a vision of the urban uncanny not present, so far as I know, in the imagery of any other Australian city, entrapped as they are in the subtropical heat and sun that white-outs menace from the popular imagery promoted by the media. Sydney, for them, is all Max Dupain.

The dust jacket to Catalano’s book tells us that Amor ‘in his commitment to figurative art’ is ‘heir to the Antipodeans’. This is true enough in an obvious sense. He has always admitted his debt to John Brack, and Clifton Pugh was a close friend. But there is a deeper sense in which Amor sustains the Antipodean tradition. For the Antipodeans were essentially Melburnians, but they were not, of course, the pioneers of Melbourne’s own distinctive modernism. That was the achievement of the small circle of artists who snugly nested in Heide during the early 1940s, now known as ‘The Angry Penguins’. They promoted a figural expressionist tradition, in the broadest sense of the word, that evoked a Melbourne psyche in the visual arts that has endured. The Angry Penguins were, in other words, the precursors of the Antipodeans – that is what the word in the title of that famous book, Rebels and Precursors, by Richard Haese, really means, although this is rarely if ever recognised. Between them, the Angry Penguins and Antipodeans established an enduring Melbourne tradition from which Amor’s art now emerges as a revenant.

Andrew Sayers, in his Australian Art (OUP, 2001), an ambitious revisionary attempt to write our indigenous and settler art as one continuous narrative, says that ‘the Antipodean Manifesto had little appreciable effect upon Australian art’. That may be an over-hasty judgment. Had he been present at the Niagara Galleries when John Button launched Gary Catalano’s book, the occasion packed with the young and old all the way down the stairs, he might have been given pause for thought. Something was happening. This was more than a media event. Amor produces the kind of art that is capable of penetrating into our culture rather than twist on the eternal merry-go-round of avant-garde art.

In 1959, the Antipodean Manifesto theorised a position that was already in practice since the 1940s. But, in Australia, most art historians (and those Nescafé historians known as curators) have convinced themselves that all art theory proceeds from Europe (or occasionally America). It is an area of our culture that continues to suffer from chronic (if not endemic) cultural cringe.

I have no interest to disclose. I have only met Amor four times in my life, all brief encounters – once in the mid-1980s when he called in unannounced at lunchtime to seek payment for a large linocut of his I had bought shortly before. He was then obviously strapped for cash. Again at a Clif Pugh retrospective at Monash University shortly after Clif’s death. Then, quite by accident, I ran into him in Canberra at the War Memorial Museum when he arrived to be vetted as our Official War Artist for East Timor. And, most recently, at the launching of Catalano’s book, looking somewhat harassed among a dense pack of admirers. I don’t think he recognised me. Book launchings and art-show openings stimulate amnesia. Not places for solitary watchers.

Comments powered by CComment