- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Eclectic Picture Book

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The picture book format is the workhorse of children’s literature. It is expected to entertain and enlighten audiences ranging from infants and toddlers to young adults. Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, the quintessential picture book for very young readers, introduces some basic concepts through simple text and colourful collage. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Isobelle Carmody’s fantasy novel, Dreamwalker, published earlier this year with illustrations and design by graphic artist Steven Woolman, has sophisticated teen appeal.

In the midst of this vast range of publications are those picture books written to give young children a better understanding of the world. Through illustration and a storyline, information is conveyed. There is usually some recognition on the part of the creators that the child will not just be handed the book to read independently but rather, initially, it will be read to the child by a parent, teacher or interested adult. The stories often raise questions and are catalysts for further discussion.

Jenni Overend’s Hello Baby (ABC Books, $12.95 pb), originally published in hardcover in 1999, is now available in paperback. It is an excellent example of a picture storybook written to help young children make sense of a lifechanging experience, in this case the birth of a sibling. The narrator is Jack, the family’s youngest child. This is his first time as an active participant in the preparations for the home birthing. He helps lay out the clothes for the baby and bring in more wood for the fire. He tries out Anna the midwife’s ‘microphone’ for listening to the baby’s heart and notes the ‘oxygen in case the baby needs it’.

Mum has warned Jack that she will be making lots of noise to help her with the labour and he says, ‘she’s right – every few minutes she yells so loudly the whole town will know we’re having our baby today!’ Jack sees the baby emerge and confirms that it is a boy. ‘Anna gently pulls the cord between Mum’s legs and out comes a big purple and red shape’, the placenta, which she announces is very healthy. She then instructs Dad to cut the cord using ‘special’ scissors. As the family settles in for a quiet sleep after an exciting day, Jack sees the baby snug between Mum and Dad where he’d like to be. He crawls in next to Dad where it is warm and he, too, is cuddled. It’s a comforting way to end the story.

Adults might consider how to use Hello Baby. While most families do not opt for home birth, many are choosing birthing centres that allow children to observe the birth of a sibling. And even if Mum goes off to have the baby in a maternity hospital, the book provides a starting point for discussion about what will be the same and what will be different about the hospital experience. Julie Vivas’s gentle illustrations in colour pencil and watercolour will help parents introduce and demystify the concept of childbirth to children whether or not they are awaiting the arrival of a new baby in the family.

The picture book format is used to tell an entirely different story in My Dog by John Heffernan (Scholastic, $24.95 hb) with watercolour illustrations by Andrew McLean. My Dog, dedicated ‘to the victims of ethnic cleansing’, places the tragedies of Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia right at eye-level for ages eight to eleven. Alija says his father, the baker, thinks the war will not come to their remote village where everyone lives together: ‘Bosnian, Serb, Croat, Muslim, Christian. We are all one people,’ he tells him. Then refugees streaming through their village bring the conflict closer. One old man dies in the village square and his little dog follows Alija home. It seems war will come even to their once peaceful place, so Alija’s father sends him and his mother to the safety of a relative some distance away. On the way they are intercepted by soldiers who take his mother, leaving Alija and his dog to fend for themselves. At night, an old man shares his bread and blanket with Alija and the trio continue the journey to the home of the old man’s daughter. The police tell him that although there are many children searching for their families, ‘they will try to tell my dad so that he can come and get me’. The last double-page spread shows Alija and his dog sitting at the edge of a town looking down the road into the distant countryside, waiting.

McLean’s expansive watercolours carry much of the emotional impact of the story. One painting conveys the sorrow on Alija’s father’s face as he enfolds his family in his arms for a last farewell. In another, it is the looks of concern and kindness of the adults caring for Alija that reassure a young reader that Alija is safe. McLean’s use of exterior landscape informs the reader of the passage of seasons and reminds us there is a big world outside the confines of a wagon or house. There is a problem with some of the text superimposed over artwork. In the book designer’s attempt to retain all the art, the print is sometimes made less legible by the artwork bleeding through the overlaid text. More planning and care should have been taken to avoid compromising readability.

Heffernan uses much restraint in writing a story that gives children a sense of the desperate situation of a war-torn country. Even McLean’s lighter, sunnier colours throughout most of My Dog offer a sense of optimism for the future. Adults may read more between the lines but young readers will not be left with a feeling of hopelessness.

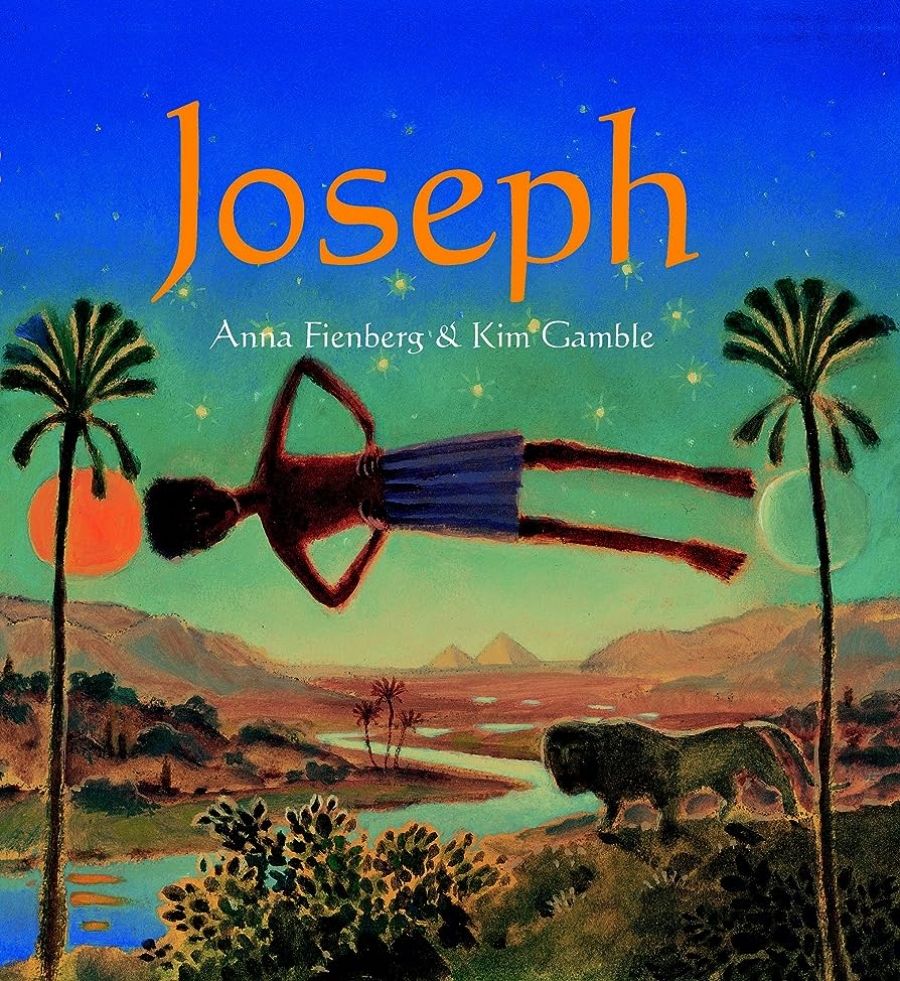

Anna Fienberg has written a lively retelling of the Biblical story Joseph, accompanied by Kim Gamble’s artwork. He paints the drama of Joseph’s life, using muted shades set against ochre backdrops to depict the desert dwelling of his early life. When the narrative moves to Egypt, Gamble intensifies his colours. Ochres brighten to oranges, light blues deepen into purples, as he evokes the vibrancy of the richer Egyptian setting. The fine details of Gamble’s oil painting are better suited to an audience of a few children snuggled close to the adult reader.

Fortunately, Fienberg’s text, which is quite charming and conversational, can stand alone for reading aloud to an entire classroom or congregation. With an eye to making the story accessible even to a younger audience, the author uses discretion with the sticky bits like the behaviour of Potiphar’s seductive wife: ‘She wanted to be close to him… Very close.’ Joseph (Allen & Unwin, $24.95 hb) is a fine addition to the genre of illustrated Bible stories.

Di Wu’s watercolour and ink paintings turn a real life, humorous incident into a fully fledged book. Young writer Jing Jing Guo’s (the author’s biography says she was born in China in 1985) story Grandpa’s Mask (Benchmark, $12.95 hb) relates an anecdote about her and her grandfather who both liked the elaborately painted faces on the actors of the Peking Opera. After they moved to Australia in 1991, she was able to watch videotapes of the Opera, but after a while that palled. One day, to amuse herself, she decided to draw her own designs for masks. With makeup in hand, but no paper available, a sleeping Grandpa became the unwitting accessory.

Newly independent readers who still enjoy liberal illustration with their text will find Grandpa’s Mask a comfortable and entertaining read, and the bright, large paintings will also work well for sharing in a group story time.

Comments powered by CComment