- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In February 1996, as Australians prepared to elect the Howard government for the first time, Paul Keating addressed a trade union rally at the Melbourne Town Hall. Keating, knowing but not accepting that he would soon be ejected from the prime ministership, ran through a commentary on the leading figures in the Liberal–National coalition. Keating’s message was that these people were second-rate and would disgrace Australia if they won power. In reference to the National Party leader, Tim Fischer, Keating attracted a big laugh when he averred: ‘You know what they say – no sense, no feeling.’ Keating, who had previously described Fischer as ‘basically illiterate’, regarded his opponent as a joke. He was not alone. There were worries about whether Fischer would be up to the task of holding down a senior ministry, especially his chosen portfolio of trade, and of serving as acting prime minister when John Howard was ill or out of the country.

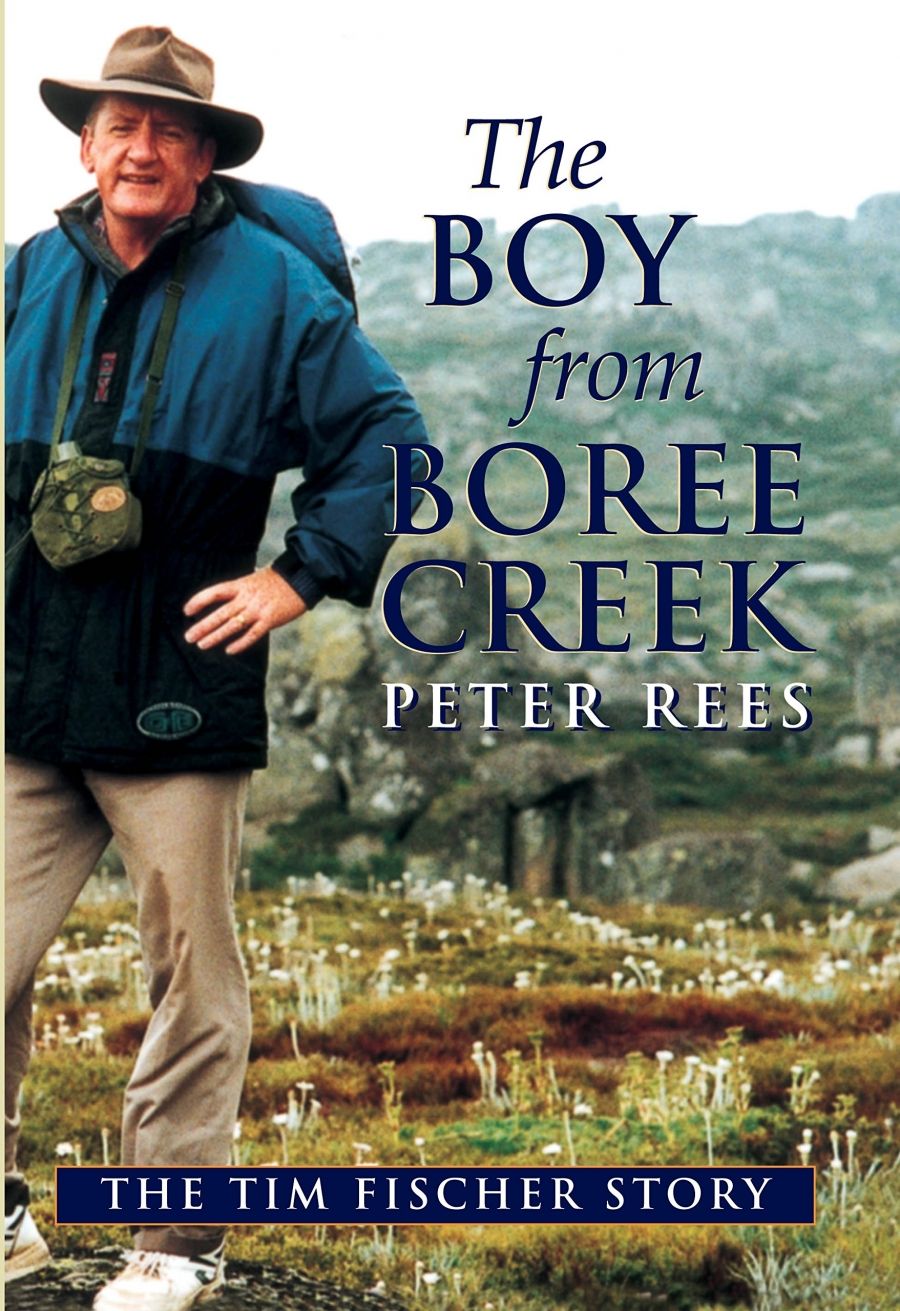

- Book 1 Title: The Boy from Boree Creek

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Tim Fischer story

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $35 hb, 354 pp

Peter Rees, in this excellent biography of Fischer, reveals that the doubts at this time ran all the way up the food chain of the coalition, into the offices of Howard and his Liberal Party deputy, Peter Costello. Indeed, Fischer recounts here that, when he was about to be invested with a ministry at Yarralumla, he was stricken with self-doubt and momentarily considered bolting from the room.

The latter is a touching revelation in a story of a very ordinary young man from rural New South Wales who overcame a speech defect, and substantial physical and social awkwardness, to attain the highest political office his party could offer. Depending on how you want to approach the Tim Fischer story, it is either a lesson in the wonders of our democracy or a cautionary tale demonstrating the mediocrity of our public figures. There can be no doubt that Fischer’s determination to make something of himself is admirable. It is not exactly rags-to-riches stuff, of course. He had the benefit of an education at Melbourne’s most prestigious Catholic boys’ school, Xavier, and notwithstanding the usual threats to rural well-being – drought, bushfire, accidents in the field – the family property at Boree Creek seems to have provided a handsome living and fair degree of certainty for the young Fischer. Even so, Fischer was clearly politically engaged as a teenager and by the age of twenty-four, after a tour of duty in Vietnam, where he was wounded, he was a member of the New South Wales parliament.

However, Fischer’s ascendancy as a political creature was not the function of some sort of Gatsby-like re-creation of self. Fischer is, to use colloquial parlance, a bit of a wacker. He is a genuine train-spotter, with a peculiar, jumpy way of expressing himself. To establish himself, first in the NSW parliament between 1971 and 1984, and then in the federal parliament as the member for Farrer, which he will vacate at the next election, Fischer employed what he called ‘edge’ publicity. This generally involved gimmicks and publicity stunts, such as taking a typing course and being photographed with a couple of comely secretarial students for a Sydney paper. As a way of getting noticed, it worked but it encouraged professional habits that never seem to have left Fischer. In later years, he has taken to embarking on a ‘Tumbatrek’ each January, a walk from Tumbarumba into the high country complete with trademark Akubra hat. Again, it was a way of garnering media coverage, but it also served to compound Fischer’s status as a novelty politician.

This might well be seen as a harsh reflection on Fischer who, as Rees’s book shows quite comprehensively, is a decent, determined, and hardworking person. But politics is about more than that, especially for a party such as the Nationals. Fischer led the party from 1990 until the middle of 1999, when he stepped down in order to spend more time with his young family, and in particular his son Harrison, who is autistic. On Fischer’s watch, the National Party became an organisation caught in a seemingly permanent existential crisis. Fischer and his staff are quoted rather self-approvingly by Rees as having seen off the One Nation threat in the 1998 election, One Nation having failed to win a lower house seat while the Nationals won sixteen. And yet One Nation attracted 936,621 primary votes to the 588,088 of the Nationals. Fischer’s take on One Nation is that its electoral base was created by Paul Keating’s recession Australia ‘had to have’. A reading of this book, however, suggests that Fischer played his part in setting the preconditions for the One Nation phenomenon with a string of attacks after the 1993 election loss against ‘political correctness’, the Mabo decision and Keating’s engagement with Asia. After the fact, Fischer now tries to suggest that his comments were attempts to get ‘balance’ into the debate – more a sign of the coalition’s ultimately self-defeating obsession with Keating than a convincing explanation of his behaviour.

The Boy from Boree Creek is probably the first rough draft of the course of the Howard government and its trials with the gun lobby, globalisation, One Nation, and the GST. That draft is necessarily viewed through the prism of how those issues affected the non-metropolitan sector, but it is nonetheless compelling and valuable. Especially intriguing are Fischer’s 1998 campaign diary notes, published here in detail. It is a credit to Fischer’s generosity that he has made them available and to Rees’s skill as a journalist that he has made them so readable. These personal reflections go some way to modifying the inescapable conclusion that in his long career Tim Fischer sought a little too much ‘edge’ publicity for his own good.

Comments powered by CComment