- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gilbert White, in 1789, declared that ‘the language of birds is very ancient and, like other ancient modes of speech, very elliptical: little is said, but much is meant and understood’. How then to portray the speakers of such language? How to give them meaning and understanding as well as plumage?

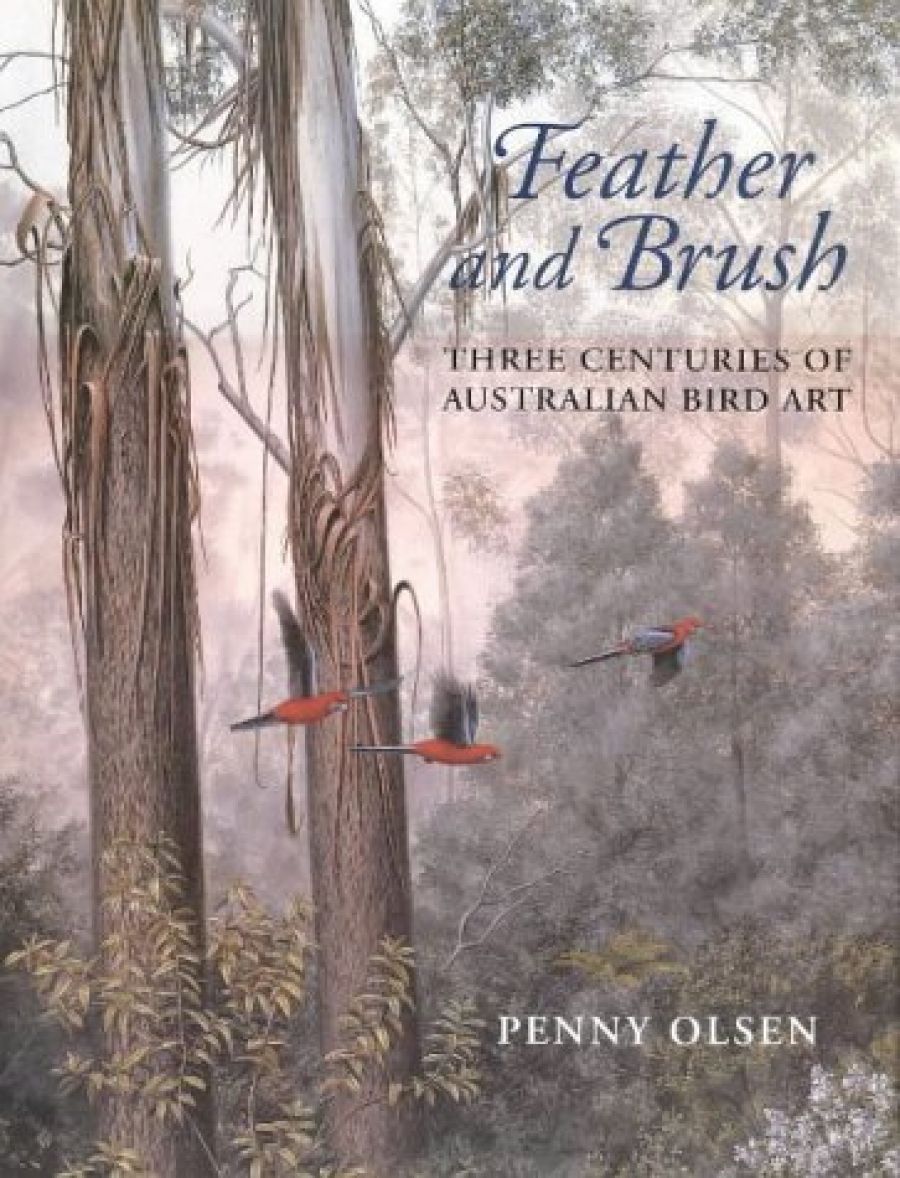

- Book 1 Title: Feather and Brush

- Book 1 Subtitle: Three centuries of Australian bird art

- Book 1 Biblio: CSIRO Publishing, $69.95 hb, 240 pp

In Feather and Brush, Penny Olsen tackles the intersection of birds and art in Australia over three hundred years. In this very beautiful book, she presents the reader with an enormous range of representations of avian personalities: the historic, the impressionistic and the scientifically accurate. Her choices and the accompanying text are guided by her sure sense of what makes for understanding, for empathy and for celebration of the birds themselves. Birdos have a word for this: ‘jizz’. This little word gathers together the indivisible whole that gives a sense of a bird, including not just its appearance, but also its demeanour and spirit. Olsen’s determination to privilege jizz gives her space to explore the partnership between science and art in these bird-works, and to give them equal airing. Olsen’s strategy is to celebrate the history of bird art as a context for both art and science, as their shared space, where they have grown together.

Sometimes the history in art is more important than the aesthetic. It was often serendipitous artists who produced the images of birds as seen by the first European eyes visiting and later invading Australia. These artists were generally not trained in the art or science of natural history. Their naval training did, however, provide drafting skills for colonisation, and their ‘eye’ captures a particular way of seeing the world. In some cases, where the first specimen for an original description under the Linnaean system of taxonomy was lost, it was the drawing, painting or engraving that became the basis for description, and therefore the ‘type’. The Port Jackson Painter’s rather startled Red Goshawk was one example of this.

Olsen has not neglected the most problematic history, the history of the present. Thirty-four short biographies of some of our most exciting and varied current bird artists provide very personal histories for some intriguing contemporary art. Some, like Richard Weatherly, whose Crimson Rosella makes such a beautiful front cover for the book, have come to bird art after years of observing wildlife as a child. Glenys Buzza’s spirited ink-paintings of ‘mood and movement’ are very different in interpretative style, but also owe their origins to childhood wanderings in nature. Raymond Harris-Ching came to birds as a challenge to art, as part of a wider sense of making ‘sense of what he sees’, and was not really motivated by either natural history or conservation imperatives. Yet his detailed frontispiece portrays an intriguing juxtaposition of natural history specimens, alive and dead, including the rare Albert’s Lyrebird specimen from the H.L. White collection of Museum Victoria. The famous Cayley (What Bird is That?) question mark in the centre of the work, suggested through the neck of a Magpie Goose, offers a visual leitmotif for the book. History, scientific identification and artistic intensity come together in this image, equal partners, yet making together something larger than any of them alone.

The book for me has only one shortfall: it would have benefited from some views from the ‘eye’ of first Australians. The X-ray art of some northern Aboriginal traditional artists from pre-contact times conveyed excellent understanding of the internal physiology of bird species more than three hundred years ago. And in the post-contact era, particularly in recent years, there are many exciting examples of Indigenous bird art and sculpture throughout Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. Although the one hundred artists already represented are a truly varied group, some Indigenous works would have enriched the book’s appeal and provided a balance to largely European or settler visions of birds.

One of the great strengths of the book is that, although she is a distinguished raptor specialist herself, Penny Olsen never allows science to dominate her commentary of the images, never implies that the art is in ‘service’ to science. At times, her irrepressible scientific eye sees things that an art connoisseur might have missed. She notes that the famous John Gould, who himself combined art, natural history and good writing to produce the nineteenth century’s most important works on Australian birds, normally depicted birds alone or in pairs. But not the Superb Fairy-wrens. His image of two males attending a female captured the essence of what we now call ‘co-operative breeding’, a breeding strategy relatively common in Australia and other resource-limited southern lands, and rare in Gould’s native Europe. Ian Rowley’s work at CSIRO since the 1950s has done much to explore and document this phenomenon, as Olsen notes. She is also unafraid to make artistic judgements, and makes them openly and without difficult jargon. She neatly sidesteps the sterile debate about art-versus-illustration by quoting the artist Peter Slater’s comment that ‘the good ones are worth looking at, whether illustration or art’. In this carefully designed book, they are, indeed, all ‘worth looking at’.

Comments powered by CComment