- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Since the Federal Parliament moved to the house on the hill, the rose garden on the Senate side of the Old Parliament House has been neglected and uncared for. Escapism, from parliament, from Canberra, from the intensity and claustrophobia of being locked up in a remote building, has always been a secret ambition of most politicians during parliamentary sittings. The rose garden used to be a beautiful and tranquil place to enjoy a reflective half-hour. On special days, like the opening of parliament, a military band would play in a marquee, and politicians, parliamentary staff and invited guests would stroll on the lawns, enjoying the music, an atmosphere of easy-going irrelevance, and the roses. It was like a scene from the last days of the Raj, filmed by Bertolucci.

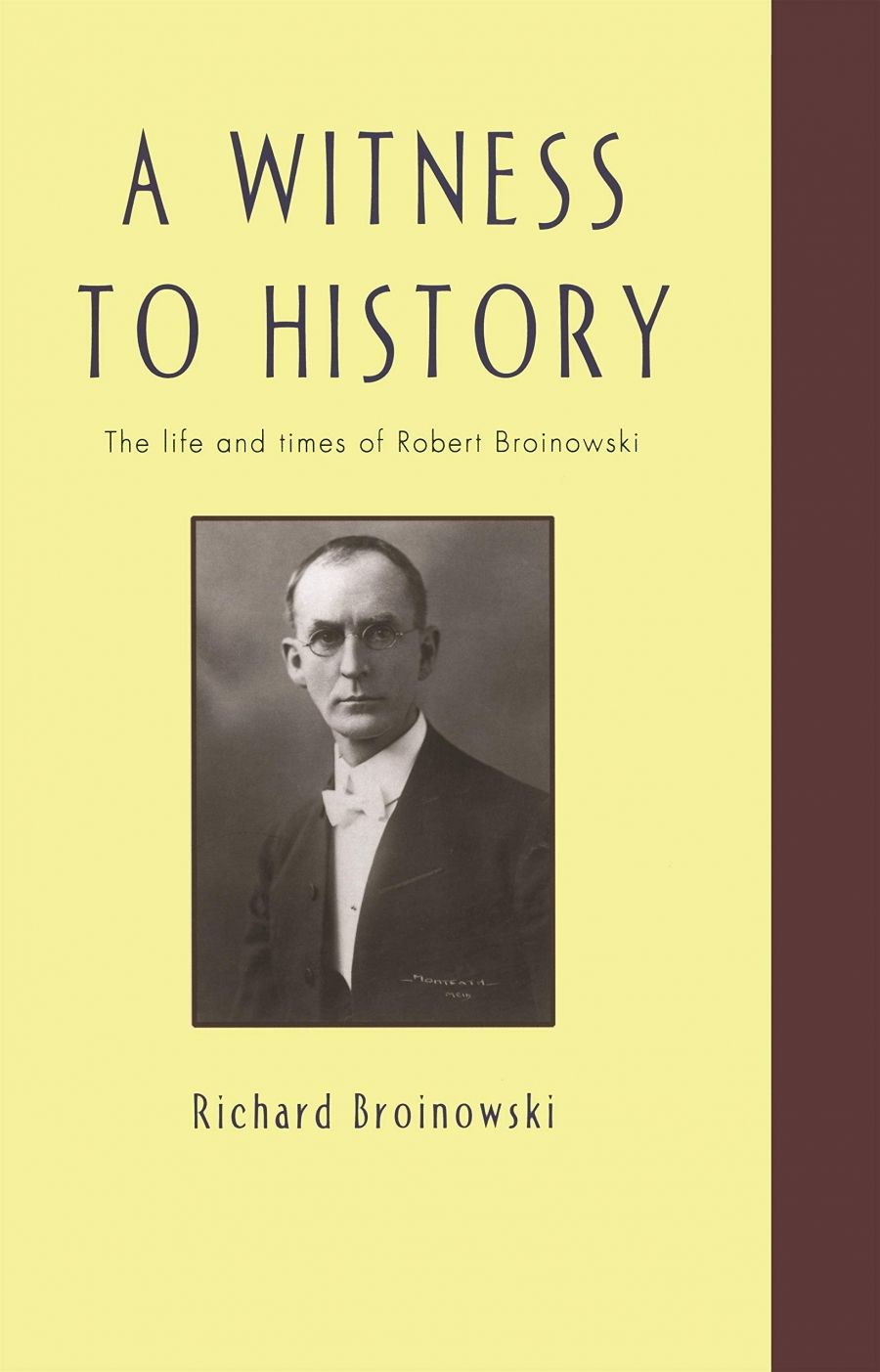

- Book 1 Title: A Witness to History

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and times of Robert Arthur Broinowski

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $44.95 hb, 257 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rjngD

Broinowski was the son of a Polish migrant, Gracius Broinowsky, who followed an itinerant life in Australian until he found his niche as an art teacher and painter of some distinction. In 1902, Robert Broinowski began his lifelong career as a bureaucrat, starting as a civilian clerk in the fledgling Commonwealth Defence Department, situated in Melbourne. Between 1907 and 1911, he was secretary to three defence ministers. In March 1911, he transferred to the Senate as a clerk and shorthand writer. He remained with the Senate in various roles, culminating in the position of clerk of the Senate from 1939 to 1942, when he retired from the public service.

Robert Broinowski was a conscientious public servant who sensibly managed to combine a career with a pursuit of outside interests. These included bushwalking and poetry. In the late 1930s he edited two poetry magazines, Spinner and Birth. He was also a broadcaster on various matters, including the workings of parliament, music, bushwalking, poetry and ‘Russia at war’.

A Witness to History is elegantly written by Robert Broinowski’s grandson Richard, now retired after a distinguished career as an Australian diplomat. The intro is as much about the author as it is about the subject; one senses at the beginning a dynastic ambition to explain ‘four generations of Broinowski men’. He returns to this in the epilogue, in which he takes his long-dead grandfather on an imaginary tour of Australia in the new millennium and engages him in conversation about the changes that have taken place.

The most interesting parts of this book are Richard Broinowski’s descriptions of some of the events of his grandfather’s times, like the defence debate in the early years of Federation, the moving of Federal Parliament to Canberra in 1927, and the functioning of parliament during World War II. This is the background against which he sets Robert Broinowski’s life.

The connection between this background and the facts of Robert’s career is the book’s weakest point. As the introduction explains: ‘During the decade before Federation and the hour turbulent decades that follow it, he was an observer and facilitator more than participant.’ In fact, Robert Broinowski only enjoyed a position of significant power and influence in his three years as clerk of the Senate.

Of his grandfather, as a witness to history, the author has had to rely on fairly slender material: a 1949 historical society article, ‘an uncompleted and unpublished book’, and transcripts of radio broadcasts which ‘reflect’ on some aspects of his career. Unfortunately, the prose in the extracts from these sources is more bureaucratic than imaginative. And, as his grandson observes, he was a reticent man.

As a consequence of this sparse testimony, much material is superfluous to the main theme. This includes observations of Robert Croll, a bushwalking companion of Broinowski, a chapter on his unremarkable divorce, and some stilted notes on a trip to New Guinea in 1939.

Diligent and reliable public servant and cultivated gentleman though he was, and deserving of an imperial honour which he coveted and did not receive, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that Robert Broinowski was something of a bore, lacking in humour, and insensitive to others. Undoubtedly, he took his jobs very seriously.

Thus, in upholding the dignity of the Senate, he was instrumental in banning ping-pong from the parliamentary precincts, and was not amused when, at the instigation of a journalist, a circus elephant was persuaded to put its head in the front door of parliament for a photo opportunity: ‘An elephant looks at a white elephant.’ Another journalist, who wrote a caustic article about the Senate, its members and its clerk, was banned from parliament for four months. In a letter to a friend in 1924 describing one of his poetry nights, Broinowski acutely observes, ‘you may think my letters are insufferably self-satisfied in tone’. A further letter from one of his friends to another, describes a dinner party at which Broinowski insisted on reading aloud to a tired and reluctant audience a paper he had written on Australian poetry. This, according to the letter writer, ‘took exactly an hour and twenty minutes’.

The publication of A Witness to History was supported by the National Council for the Centenary of Federation. It is regrettable in this circumstance that the author asserts that ‘in Melbourne Cabinet had invariably met in the Commonwealth offices in Flinders St’. This is incorrect and should not pass into Federation folklore. Apart from that, it has some interesting historical insights and provides a picture of a man who, whatever his shortcomings, provided some of the glue which held the federal system together in its early decades.

Comments powered by CComment